In 2007, religion reporter Cathleen Falsani sat down with a U.S. Senator who would announce his presidential candidacy the following month, Barack Obama. Writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, she had interviewed the rising Illinois politician before and spoken with him about his personal Christian faith. Noticing how much Obama invoked God and his religious convictions in political speeches, this time Falsani asked if he considered himself an evangelical.

“Gosh, I’m not sure if labels are helpful here because the definition of an evangelical is so loose and subject to so many different interpretations,” Obama responded. “I came to Christianity through the Black church tradition where the line between evangelical and non-evangelical is completely blurred. Nobody knows exactly what it means. Does it mean that you feel you’ve got a personal relationship with Christ the savior? Then that’s directly part of the Black church experience.”

During the campaign and his presidency, Obama clearly talked about his personal faith, his salvation experience, and Jesus in historically evangelical ways. By “evangelical” in the classic sense, we lean on the work of historian David Bebbington who identified four key characteristics of evangelicalism: conversionism (the necessity of a born-again experience), activism (a commitment to sharing one’s faith with others), biblicism (basing one’s faith on the authority of the Bible), and crucicentrism (a focus on the death of Jesus on the cross).

(Josue Michel/Unsplash)

But Obama avoided the “evangelical” label less on theological grounds than because of the cultural connotations that came with it. Fourteen years later, Obama’s observation seems even more prescient. Despite this historic religious meaning of the label “evangelical,” new research released last week confirms that the term comes with even more political baggage than when that senator from Illinois shied away from it.

In this issue of A Public Witness, we take a look at two new survey reports on White evangelicals and Donald Trump to consider what they tell us together about the label ‘evangelical.’ We also join the chorus of voices searching for new religious identifiers.

Trumpvangelicals

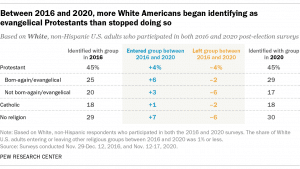

On Wednesday (Sept. 15), the Pew Research Center released analysis from their American Trends Panel in which they interviewed people right after the 2016 and 2020 elections. Looking at data from those individuals included in both surveys, Pew saw some interesting — and we think alarming — shifts about who identifies as an “evangelical.”

On the surface, the number of White evangelicals grew as a percentage of the U.S. population from 25% in 2016 to 29% in 2020. But the comparative data by Pew shows what’s going on. While 2% of White Americans who identified as “evangelical” in 2016 no longer used that label in 2020, another 6% who didn’t identify as “evangelical” in 2016 adopted the label by 2020. It’s not just that more people are identifying as “evangelical,” but there is some shifting in both directions.

Was there a large revival of born-again conversions that slipped the attention of the media? No. At least not in the historic evangelical understanding. Pew discovered a key variable among the 6% who adopted the term “evangelical” during the Trump presidency: expressing a “warm view of Trump.”

Here’s how Gregory Smith, associate director of research for Pew, explained the finding: “Between 2016 and 2020, White Americans with warm views toward Trump were far more likely than those with less favorable views of the former president to begin identifying as born-again/evangelical Protestants, perhaps reflecting the strong association between Trump’s political movement and the evangelical religious label.”

That is, many admirers of Trump who didn’t call themselves “evangelical” in 2016 then embraced that label by 2020. But was this a new-found religious identity or just a new way of expressing their political identity? This would seem to support what writer Sarah Posner recognized back in 2016: “Trumpvangelicals are the new evangelicals.”

This shift helps explain why Trump’s support among White evangelicals increased in 2020 over the already-high level in 2016. While Pew found that Trump won a higher percentage in 2020 of those who identified as “evangelical” in both surveys, his 2020 level of evangelical support was also boosted by the new “converts” to the label. More Trump supporters adopted the “evangelical” label, thus creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that evangelicals support Trump. Thus, in the Pew dataset, Trump’s evangelical support rose from 77% in 2016 to 84% in 2020.

Illiberal Insurrection

On the same day Pew released their findings, PRRI released new poll data on who Americans believe “hold a lot of responsibility” for the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. That survey adds to our understanding of the politicization of the ‘evangelical’ label.

Among all Americans, 59% blame White Supremacist groups, 56% blame Donald Trump, and 55% blame conservative media that spread conspiracies theories and misinformation about the election. Further down the list, only 41% blame Republican leaders, 38% blame liberal activists like Antifa, and 29% blame White conservative Christian groups.

When looking at religious respondents, nearly every single faith group blamed the same top three culprits. Catholics, Hispanic and Black Protestants, Latter-day Saints, Jews, those of other religions, and the religiously unaffiliated all blame White Supremacists, Trump, and conservative media the most (though in different orders and at different levels). White non-evangelical Protestants also nearly line up with the norm as they mostly blame White Supremacists (49%) and conservative media (45%), but then have a few more who accuse liberal activists (44%) than Trump (43%).

But there’s one religious demographic that sits as a radical outlier to all the others. You guessed it.

A whopping 57% of White evangelicals blame liberal activists. Even though — and we feel we must emphasize this point given that percentage — the evidence is overwhelming and clear that the claims that Antifa conducted the insurrection as a “false flag” operation are false. This was a mob of Trump supporters.

But a majority of White evangelicals buy into conspiracy theories and misinformation — from the same “media” outlets that spread conspiracy theories and misinformation about the election that helped fuel the rage we saw on Jan. 6. Thus, only 37% of White evangelicals blame White Supremacists for the insurrection, making White evangelicals the only religious demographic where fewer than half blame those who carried Confederate flags and wore shirts cheering the Holocaust as they stormed our nation’s Capitol. And only 34% of White evangelicals blame conservative media, with even fewer accusing Trump (26%).

That order of blame (mostly liberals, followed way behind by White Supremacists, conservative media, and Trump) matches the pattern of some other groups in PRRI’s survey: those who hold a favorable opinion of Trump, those who think the 2020 election was stolen, and those who believe QAnon conspiracies. It shouldn’t be surprising (but is frustrating) that PRRI also found White evangelicals were “the only religious group among whom a majority believes the election was stolen.” A full 61% had bought into this debunked lost cause of Trump. And 25% of White evangelicals believe in QAnon conspiracies, outpacing the national rate of 17%.

Perhaps the alignment of the label “evangelical” with Trumpism, as seen in the Pew report, helps explain the Trumpian attitude of self-identified White evangelicals in the PRRI poll. And this spiraling cycle can accelerate as people leave or adopt the label “evangelical” as it becomes synonymous with Trumpism, Jan. 6, and political conspiracy theories.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

When Words Lose Their Meaning

Jesus warned us that “if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.” The same can be true of words.

Words change in meaning over time. We must pay attention to such semantic shifts, lest we miscommunicate. “Egregious” originally meant really good, but now means shockingly bad. It would be an, well, egregious mistake to insist on using the original meaning today as people would make inaccurate judgements about what you think is good and bad. Or consider the shift in the word “nice,” which hundreds of years ago meant foolish or what we might today call “silly.” But ”silly” back then meant blessed. But it wouldn’t be nice today to call a blessed person silly!

The term “evangelical” is undergoing a similar transformation. Rather than a religious label describing key spiritual beliefs and experiences, it increasingly signifies one’s political tribe.

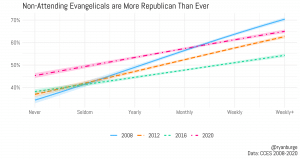

To throw in one more poll finding from earlier this year, consider some analysis by Ryan Burge, an American Baptist pastor who teaches political science at Eastern Illinois University. He noted that in 2008, 58.6% of self-identified evangelicals reported attending church weekly or more, but that number fell to 49.9% in 2020. Meanwhile, those who called themselves “evangelical” but also reported never or seldom even attending church rose from 16.1% in 2008 to 26.7% in 2020. That is, more and more “evangelicals” don’t even go to church.

Digging deeper into the data, Burge discovered that the never-attending “evangelicals” are 10 percentage points “more likely to be a Republican today than in 2008” while those who attend weekly or more are actually 5 percentage points less likely to be Republican today than 12 years earlier. (It should be noted that the data still shows more regular church attendance correlated with Republican support regardless of year.)

“Even more evidence here that ‘evangelical’ is not a religious term anymore,” Burge concluded.

That means, when someone uses the label “evangelical,” they might signal a political message to others rather than a religious one. Thus, Baylor University historian Thomas Kidd, author of Who is an Evangelical?, told Christianity Today in response to the new Pew report that “pastors in particular should realize that the meaning they attach to ‘evangelical’ may not be the same as that of some in their congregation. I suspect most pastors would not want to inadvertently signal to their congregations that they are effectively branch offices of Donald Trump’s GOP, simply by making undefined use of the term ‘evangelical.’”

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Bad News for the Good News?

We asked David Gushee, an ethicist at Mercer University and the author of After Evangelicalism, about the Pew report and what this means for the “evangelical” label.

“It looks to me as if the older religious meaning of the identity ‘evangelical’ weakened and its political meaning strengthened under the impact of the Trump phenomenon,” Gushee responded. “The older religious meaning of evangelicalism used to mean commitments like the authority of scripture, evangelism, missions, personal morality, and a godly witness in public life. Now that older meaning has been superseded by commitment to Donald Trump and Trumpism.”

Trump supporters — or those of any politician — are free to define themselves as they deem fit. The critique is not that co-optation of language is inherently wrong but that this shift in the political realm has important consequences for American Christianity that have yet to be sorted out. And as Gushee added, this linguistic transformation necessitates a critique of the evangelical movement overall.

“It certainly looks to me like Donald Trump has evangelized the evangelicals with his own toxic politics,” he explained to us. “But as many observers, including myself, have pointed out, the fact that the evangelicals were willing to be evangelized says more about them than about Trump.”

To that point, Anthea Butler, a religious studies and Africana studies professor at the University of Pennsylvania and author of White Evangelical Racism, argued in an MSBNC column after the Pew report, “Now that those who don’t know the theological beliefs of evangelicalism are identifying themselves as such, there should be no confusion about what evangelicalism really is in America: a full-fledged religious political movement whose allegiance is to the Republican party’s issues and to whiteness.”

Embracing the term “evangelical” without appreciating its evolving meaning could be a way of unintentionally adding more credence to a dangerous political ideology that preaches conspiracies about “stolen” elections, Jan. 6 “liberal” insurrectionists, and QAnon “heroes.” We must not only reject the dying label but also stand against the political heresy taking over so many in our churches.

A “Baptist Missions” food pantry with pro-Trump signs in June 2021 in Wright City, Missouri. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

In this moment, we have clarity about what is lost. A term that used to signify something important no longer carries the same meaning. Our politics, with the help of many professed Christians, has warped and disfigured the Church’s language. The American Church’s witness is damaged by ongoing corruption of its language. The rescue effort cannot wait.

As Robert P. Jones, CEO of PRRI, reflected in his own Substack e-newsletter about the new poll his organization released: “The time for benefits of the doubt has expired. We must face the disheartening reality before us and act to excise the cancer of White Christian extremism from our body politic and our churches. If we have any hope of preventing it from further metastasizing, we will need the courage and voice of every White Christian, lay and clergy alike, to say a collective ‘no’ to this debasement of Christian theology that is eroding the foundations of our democracy.”

To that, we raise our voices of support as non-evangelical evangelists.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood