Michael Flynn hopes to see a revival in America. But the disgraced former Army lieutenant general and QAnon adherent’s vision seems a bit like something out of the book of Revelation.

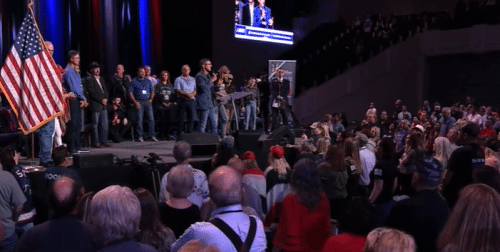

During a “Reawaken America” event Saturday (Nov. 13) at Cornerstone Church in San Antonio, Texas, Flynn joined a number of other Trumpian politicians and preachers, like an anti-vax pastor trying to defeat U.S. Sen. James Lankford, pillow-hugging conspiracy theorist Mike Lindell, and traveling Christian Nationalist musician Sean Feucht who followed Flynn on stage to “raise a hallelujah.” The top star in the promotional materials, Flynn argued the U.S. must be united under one religion.

“If we are going to have one nation under God, which we must, we have to have one religion,” Flynn preached. “One nation under God and one religion under God.”

His comments quickly received denouncements as dangerous, undemocratic, and Christian Nationalism. The broader context of his comments prove these assessments.

Flynn, who briefly served as President Donald Trump’s first U.S. National Security Advisor and later got a pardon from Trump for lying to the FBI about secret conversations with a Russian official, argued that religion “is the foundation of this country,” which was “created as a Judeo-Christian country with the beautiful set of values and principles that we have.”

“God Almighty is involved in this country because this is it,” Flynn added. “This is the last place on Earth. This is the shining city on the hill.”

And earlier in the 10-hour-revival service (that suffering through is proof that hell exists), Flynn referenced his past service in the military and declared there are “no atheists in a foxhole because you have to believe that Christ, that God, that your faith has got to be strong.”

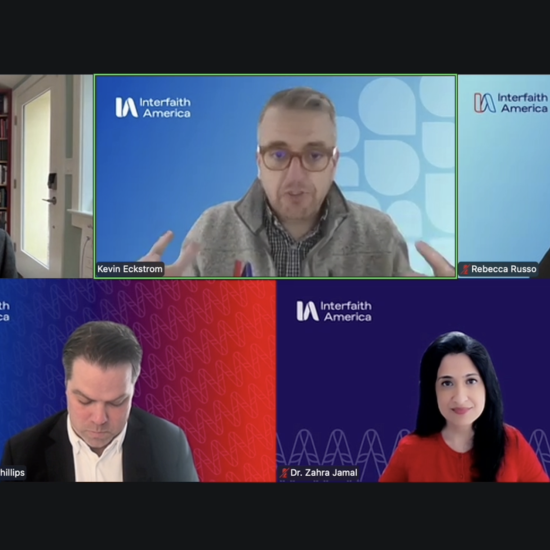

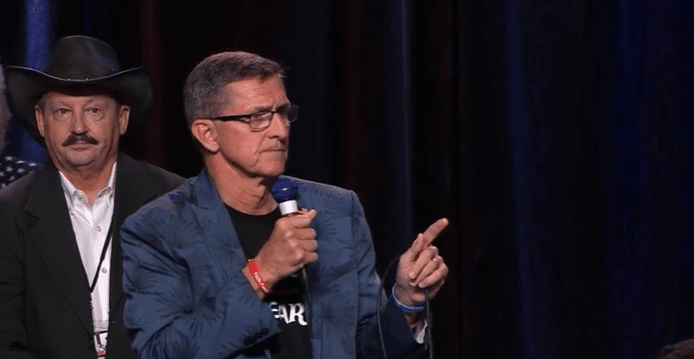

Screengrab of Michael Flynn speaking at the “Reawaken America” event in San Antonio, Texas, on Nov. 13, 2021.

While many commentators correctly noted that Flynn’s Christian Nationalism is historically skewed, theologically inaccurate, and democratically unjustifiable, Flynn also exposed a real problem — but not the point he thought he was making. His statements and beliefs build upon the foundation of a civil religion employed by politicians and preachers for decades to further nationalistic goals. If we are a nation under a god, then that logically implies a unifying religion. Flynn is wrong but not in the way everyone seems to think.

So, while we reject Flynn’s call to create an allegedly “Christian” nation united in one religion, it would be too convenient to merely dismiss the problem as the rantings of a man who falsely thinks Trump won the election. In this issue of A Public Witness, we testify about the uninspiring history of “one nation under God” and civil religion. And we preach about a better way to think about our Christianity and citizenship.

Followers of the (American) Way

In 1954, the U.S. officially added “one nation under God” into the Pledge of Allegiance. For the previous 62 years the pledge remained agnostic. Why this omission? Because of the socialist Baptist pastor who originally wrote it.

The son of a minister in New York, Francis Bellamy followed in his father’s footsteps. The younger Bellamy attended Rochester Theological Seminary (now known as Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School), and he pastored Baptist churches in New York and Massachusetts. He also wrote for a number of publications, including Youth’s Companion.

For the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus reaching the Americas, the 37-year-old Bellamy wrote a salute to the U.S. flag to be used for Columbus Day celebrations. Since Youth’s Companion funded itself in part by selling American flags, pushing a patriotic salute was good business. The Sept. 8, 1892, issue carried Bellamy’s version enshrining a separation between God and Pledge. Other than an edit in 1942 to change “my flag” to “the flag of the United States of America,” just to make sure there weren’t any German-Americans being tricky during World War II, the pledge remained godless.

As Baptist historian Bruce Gourley explained, Bellamy’s text “intentionally reflected the Baptist heritage of church state separation.” And Bellamy’s descendants have said he wouldn’t have wanted the “under God” phrase added. So, yes, the original pledge left God out because a Christian minister wanted it that way.

But more than two decades after Bellamy’s death, politicians overrode his vision. After hearing a sermon from a Presbyterian pastor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower urged Congress to add “under God” to the pledge in 1954 as the nation found itself in the Cold War with the atheistic, socialist Soviet Union. With ‘God’ in the Pledge, the U.S. increased its rhetorical arsenal in the global struggle.

There’s more to the story, though, than the Cold War. Kevin Kruse, a professor of history at Princeton University, documented the religious-political revival of the Eisenhower era in his book One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invested Christian America. Although pushing different economic ideologies, both Republicans and Democrats used the idea of a nation “under God” to advance their competing domestic agendas. In a time when the two political parties voted alike on very few bills (proving, again, that there’s nothing new under the sun), Kruse noted, “Only the broad concept of ‘one nation under God’ proved elastic enough to bring them together.”

With the addition to the Pledge, Kruse wrote, “the phrase ‘one nation under God’ quickly claimed a central position in American political culture” as “an informal motto for the country” to “unite Americans from across the religious and political spectrum.”

The pastor who inspired Eisenhower claimed that without God in the Pledge, any republic could use the words to describe their nation (which implies that only the U.S. could lay claim to a covenantal relationship with God). For this minister, God stood for “the American way of life.” What did that mean? That pastor, George Docherty of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C., explained it in commercial terms: “It is going to the ball game and eating popcorn, and drinking Coca Cola, and rooting for the Senators. It is shopping in Sears, Roebuck. It is losing heart and hat on a roller coaster. It is driving on the right side of the road and putting up at motels on a long journey.”

Kruse argued phrases like “one nation under God” are “often overlooked” because they seem like just “everyday things.” But such rhetoric is not insignificant. Far from “symbolic flourishes with little substance,” Kruse added, these phrases today spark Supreme Court cases, political controversies, and campaign messaging. Even though a late addition to our political rhetoric, phrases like “one nation under God” now pack a potent punch.

Fervently Civil

Grasping this history, you won’t be surprised to learn that the United States is a very religious country but not in the way people often assume. Diverse in belonging and belief, national unity is found in the observance of “civil religion.” The sociologist Robert Bellah borrowed this term from Jean-Jacques Rousseau and famously applied it to the American context in 1967. It has been misused and abused ever since.

Bellah was not describing a nation worshiping its own self, as many commentators assume. Rather, he was talking about a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that are “elaborate and well-institutionalized” with their own “seriousness and integrity.” This faith evolves over time but includes a generic “God” who is actively concerned about America and more interested in “order, law, and right than to salvation and love.” At times it portrays our nation as a new Israel, and in other moments it extols the virtues of sacrifice and martyrdom.

The important thing to grasp is that this civil religion is not Christianity or any other sectarian tradition but something every American can practice. As Bellah wrote, “[American Civil Religion] borrowed selectively from the religious tradition in such a way that the average American saw no conflict between the two. In this way, the civil religion was able to build up without any bitter struggle with the church powerful symbols of national solidarity and to mobilize deep levels of personal motivation for the attainment of national goals.”

Presidential addresses regularly invoke this civil religion to increase support for various causes. Military cemeteries are set aside as sacred sites to which pilgrimages are made. National holidays, such as Memorial Day or Thanksgiving, express common rituals that bind us together as a religious community.

“It has its own prophets and its own martyrs, its own sacred events and sacred places, its own solemn rituals and symbols,” Bellah explained. “It is concerned that America be a society as perfectly in accord with the will of God as men can make it, and a light to all nations.”

While many presidents serve as priests of this national creed, few represented it as well as Eisenhower (there he is again), who remarked in 1952 that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is. With us of course it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with [sic] all men are created equal.”

Civil religion is nationalistic but non-sectarian. It fosters loyalty and pride in one’s country, while binding people together in common cause. The goal is to make citizenship a transcendental experience that inspires citizens to take whatever action is necessary, including making the ultimate sacrifice, out of fidelity to the American experiment.

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

The Actual City on a Hill

Michael Flynn’s democratic sin was violating this communal religious project. With civil religion, it’s okay for everyone to profess that we are “one nation under God” so long as nobody specifies the deity involved. The vagueness allows for broad agreement, even though every individual citizen means something different in their affirmation (factoring in atheists, polytheists, and non-theists complicates things, of course, but few in our society let such concerns get in the way).

To be absolutely clear, we abhor the specifics of Flynn’s faith. His argument that the U.S. is the biblical “city on a hill” is nothing short of heresy. If you actually read your Bible (unlike, we presume, Flynn), you’ll find Jesus clearly tells us who makes up this city: his followers. It’s a metaphor for a new kingdom, not an actual city or nation. And this city by definition transcends human boundaries so it cannot be confined within the jurisdiction of one nation.

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer explained, “The followers [of Jesus] are the visible community of faith; their discipleship is a visible act which separates them from the world — or it is not discipleship. And discipleship is as visible as light in the night, as a mountain in the flatland.”

While Flynn rejected this theology, he’s merely the latest in a long line of politicians to co-opt Jesus’s city as a blessing for this American nation. Flynn even situated himself in this lineage by noting that both John Winthrop and Ronald Reagan invoked the “city on a hill” language this way. Flynn went a bit further to not only steal the language but to even suggest that when Matthew wrote it, he was actually prophesying about the United States.

“This is the city on the hill,” Flynn declared with the earnestness of a televangelist. “They’re talking about the United States of America, talking about the United States of America. ‘Cause when Matthew mentioned it in the Bible, he wasn’t talking about the physical ground that he was on; he was talking about something in the distance.”

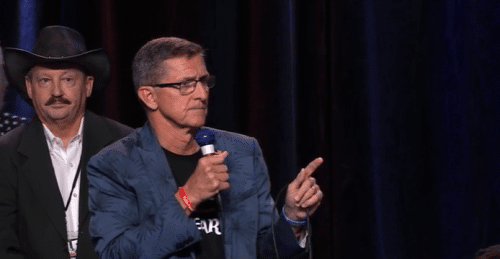

Screengrab of Michael Flynn speaking at the “Reawaken America” event in San Antonio, Texas, on Nov. 13, 2021.

Now the Matthew verse becomes not just a metaphor to steal but an unbelievable prediction of a nation to come (perhaps Q told Matthew this along with a prediction about waiting on the grassy knoll for JFK Jr. to return). Although Flynn’s words seem outlandish, many Christian Nationalists hold to such a general philosophy. Unmoored from informed biblical interpretation, this dangerous ideological movement and its growing influence poses significant risks both to the health of our nation (like on Jan. 6) and to churches (like on Saturday at Cornerstone in San Antonio).

And Cornerstone, founded by televangelist John Hagee, provides quite the case study of a people gone adrift. Over the past few decades, Hagee racked up a record of controversial statements, as if he’s in some sort of challenge with Pat Robertson and Jim Bakker to see who can score the most points for offending people. Hagee’s record clearly demonstrates anti-Catholicism, anti-Semitism, and Islamaphobia. Throw in his Christian Zionism and his “blood moon” prophecy and you’ve got quite a contender!

Long active in Republican politics, Hagee found himself a political pariah in 2008. After endorsing Republican presidential nominee John McCain, controversy erupted about Hagee’s hateful remarks against various groups of people. McCain announced he found comments by Hagee “deeply offensive and indefensible.” He added that he repudiated Hagee’s remarks and “must reject his endorsement as well.”

A few years later, however, Hagee found political redemption in the form of a profane businessman who mocked McCain’s time as a POW and called the Republican Senator a “dummy” and a “loser.”

Now Hagee’s church hosts Trumpian events like the Flynn revival that included a call-and-response chant with the congregation to declare, “Let’s go, Brandon,” which is code for an obscene denouncement of President Joe Biden. Whatever the hill this is, it’s not shining good deeds that glorify God in heaven.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Worshiping a Generic God

Flynn and Hagee not only represent a distortion of Jesus but also a threat to democratic principles. Not only is Christian Nationalism a heresy, but it is also inherently anti-democratic because it seeks to impose a religious test on our national identity. We saw this as insurrectionists listening to Flynn and Trump violently attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 while carrying Bibles, Jesus signs, and Christian flags.

By definition, such a theocracy can never function as a democracy. We are a nation that includes Christians and Confucians, Buddhists and Baháʼís, atheists and agnostics, Jews and Jedis, and much more. Flynn and his fellow horsemen of the insurrection want to deny basic freedoms to democratic citizens and turn followers of Jesus into idolaters of an empire.

But Flynn and other Trumpian preachers didn’t invent this problem. And in some way, Flynn is merely taking the Eisenhower project to its natural conclusion. Although civil religion provided a unifying nationalistic faith, as Bellah noted, it does so by co-opting Christian words and symbols.

In that way, Flynn is right. If we are to actually be one nation under God, then that logically implies a privileged religion and the disenfranchisement of those outside that faith. To seek a nation with “one religion” or even a nation “under God” is to create a religious test that strips some people of their citizenship.

That’s what Flynn would do, but it was also the belief of the Presbyterian pastor who inspired Eisenhower to push to christen the Pledge. That pastor claimed in his sermon that atheists may be “good neighbors” but are “spiritual parasites” as they live off the society he felt came from the God who created this nation. Thus, he argued, “Philosophically speaking, an atheistic American is a contradiction in terms.” And Eisenhower said, “amen.” But what that pastor, Eisenhower, and now Flynn fail to understand is that atheists can still be fully American.

(Luke Stackpoole/Unsplash)

The problem with civil religion remains that there is no such thing as a generic “god.” We should stop pretending that god exists. Whenever someone talks about “God,” they always have something specific in mind. For the two of us, we do not worship the vague god of civil religion nor the partisan deity imagined by Christian Nationalists. We bow down before the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. We confess that Jesus Christ alone is Lord. We praise the One who is “God of gods and Lord of lords.”

The God we worship cannot be the god of civil religion (or Christian Nationalism). And Christians, who are taught that they cannot serve two masters, cannot pledge allegiance to both God and a generic American “god.” So, we should stop pretending and just toss out “one nation under god” and “in god we trust” as governmental statements. Let’s stop acting like some people aren’t fully American because of their faith, or that some followers of Jesus aren’t fully Christian because of their nationality.

Although Flynn violates democratic principles and Christian theology with his “under god” remarks, he also inadvertently exposes how civil religion does the same things. We don’t need to establish a religion or a god to run our democracy. As that Baptist socialist who wrote the Pledge over a century ago did, it’s time to just leave God out of it.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood