WASHINGTON (RNS) — U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock and U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, both Democrats and one an ordained minister, made the religious case for protecting and expanding voting rights on Thursday (Nov. 18), championing the “sacred” right to vote in a wide-ranging discussion that also touched on whether God is Black.

The two lawmakers appeared at “Race, Religion and the Assault on Voting Rights,” the inaugural event at Georgetown University’s Center on Faith and Justice, headed by Rev. Jim Wallis, founder of the liberal-leaning Christian group Sojourners.

“Voting rights must also be named as a faith issue — even a test of faith,” Wallis told the crowd.

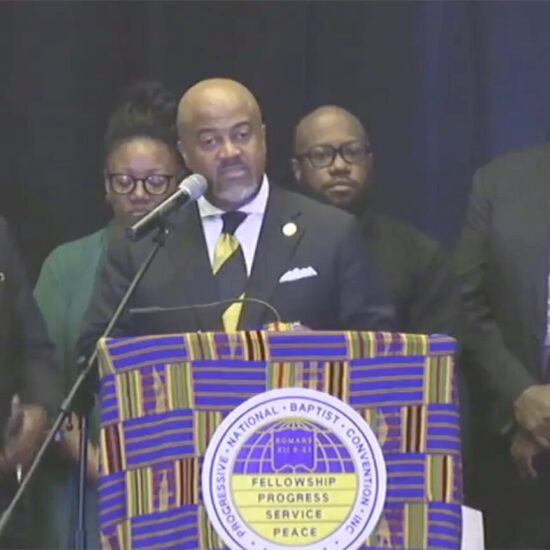

U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock of Georgia speaks during the Center on Faith and Justice launch event at Gerogetown University, on Nov. 17, 2021, in Washington, D.C. (Phil Humnicky/Georgetown University)

Warnock expressed a similar sentiment throughout the session, at one point describing the act of voting as “a kind of prayer for the world we desire, for ourselves and our children.” The Georgia senator’s views on voting, he said, are connected to his beliefs surrounding salvation, which he sees as a “broadening of communal space.”

“I believe (voting) is sacred, because at root the vote is about your voice, and your voice is about your human dignity,” he said, adding that voting is a “covenant that we have with one another as American people.”

But he warned that the bevy of state-level voting bills backed by Republicans constitute an existential threat to the right to vote and, ultimately, American democracy itself. It’s a position echoed by faith groups — many led by Black pastors — that have staged massive protests or threatened boycotts against the laws passed throughout 2021.

The demonstrators — including Warnock — have expressed particular opposition to provisions such as requiring voter ID, shortening voting hours, banning average citizens from handing out food and water to people waiting in line to vote and allowing more partisan oversight on the voting process.

“Instead of people picking their politicians, politicians are trying to pick their people,” Warnock said.

As a remedy, the senator pointed to the Freedom to Vote Act, which would institute broad protections for voting rights. He referred to it as a “compromise bill” developed after another, more wide-ranging bill — the For the People Act — failed to secure support from party moderates such as West Virginia’s Sen. Joe Manchin. Warnock voiced frustration with Republicans who continue to block the new bill’s passage by using the filibuster, a Senate rule that requires a 60-vote supermajority to pass many major pieces of legislation.

“I’m a preacher — it’s never too late to get saved, to get religion,” Warnock said of his Republican colleagues.

Sewell, who represents Alabama’s 7th Congressional District, urged passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which she has repeatedly introduced to Congress over the course of several years. The bill, named after the late civil rights icon and Georgia congressman John Lewis, would restore and strengthen aspects of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was gutted by a pair of Supreme Court decisions over the past decade.

“At the end of the day, our democracy, this Constitution, this exercise in form of government, if you will — the base of that is the right to vote,” Sewell said. “It’s fundamental — as John (Lewis) would say, ‘It’s almost sacred.’”

In a question-and-answer session, one student invoked late Black liberation theologian James Cone to ask if God, who “sides with the oppressed,” is also Black. Joking that he wanted to have a “longer theological conversation” with the student afterward, Warnock answered by appealing to a Christian faith that focuses on the poor and marginalized.

“I come out of a tradition, the Black church … it is the anti-slavery church. It is the freedom church,” he said. When other Christians attempted to use the Bible to justify the institution of slavery, he pointed out, the Black church “held vigil to a vision of humanity that embraces all of us — and it did that when, in the words of the old spiritual, ‘We couldn’t hear nobody pray.’”

Asked how she navigates being the only Democrat, woman, and person of color in the Alabama delegation, Sewell quoted Eleanor Roosevelt, saying, “No one can you make you feel inferior unless you give them permission.”

Having grown up in Selma, surrounded by the legacy of the civil rights movement, Sewell said: “My job is to use my voice in that seat and to create more chairs around the table that are filled with people who are women” and people from diverse backgrounds.

“I sit in seats to use the voice that God gave me,” she added.

Warnock, for his part, signaled that his faith remains central to his life and work.

“I’m not a senator who used to be a pastor. I’m a pastor who happens to serve in the United States Senate,” he said.

He recalled times when faith failed to impress a moral vision on society. In Nazi Germany, he said, “the church didn’t stand up.”

“It retreated to a kind of insular vision that says, ‘That’s not our business,’ or they gave over to a kind of Christian Nationalism,” he said. “The truth is, slavery wouldn’t have lasted so long, and segregation wouldn’t have been so intractable, were it not for the cooperation of people who worship every weekend.”

A defining question of the moment, he said, is “I know what you sing about in your hymns, but who — and what, really — is your God?’”

Asked by Wallis to offer a “benediction” to close out the event, Sewell provided attendees with a list of ways to protect voting rights moving forward.

“I want you to vote, volunteer, organize, turn out and elect people who will do the right thing,” she said, sparking a standing ovation.