Every Christian knows the great commandments: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” (Luke 10:27). And in the next verse, the lawyer asks Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” It’s a question that matters when we think about every aspect of our lives, including what we wear. Clothing is a ubiquitous commodity that almost every culture in the world shares in some form. One of humanity’s earliest inventions, it has grown into a massive industry, with pre-pandemic estimates of around $2.5 trillion in global annual revenues.

Lizzy Case

Yet we often have no clue whose hands actually sewed our clothing’s seams or whose land produced the cotton that goes into even basic garments like t-shirts. In the cotton industry alone, more than 20 million cotton farmers and workers in gins, mills, and garment factories produce the clothing we wear.

This is not only a global problem – it’s a theological one. As followers of Jesus, we aim to observe the two great commandments, love God and love neighbor, with our whole lives. But who is our neighbor when it comes to clothes? Garment workers are the engine driving the global clothing system. Yet they are often dismally compensated for their skilled labor and forced to work in unsafe conditions. If we cannot care for the people producing our clothing, can we truly say we are loving our neighbor?

In many ways, we live in a global village. Through our clothes we’re connected to cotton-growing fields, wool-producing sheep, farmers harvesting these raw materials, and the many, many hands transforming them into fiber, textiles, then dyeing, cutting, sewing, finishing, and shipping the final garments to the stores we buy from.

In this kind of webbed world, our neighbor is one who is both far and near. According to theologian Larry Rasmussen, our neighbor is, “the articulated form of creation to whom justice, as the fullest possible flourishing of creation, is due.” Existing in relationship to one another is our primary reality, and in the Christian lens, our neighbor is a person who is, “before all else, beloved (by God).”

As Jesus-followers, not only are we oriented in love towards our neighbors but we are also called to take action. In Luke 10, Jesus defines the neighbor “not in a theological sense, but in a life situation.” It is not the person who simply believed they were a neighbor – it is the person who, in the words of liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez, “proved themselves neighbor to the man.”

Theologian Sharon Ringe phrases it this way: “No one can simply have a neighbor; one must also be a neighbor. … The story simply stands as yet another challenge to the transformation of daily life and business as usual, which lies at the heart of the practice of discipleship.”

This mandate of our Christian faith stands at stark odds with the current situation of many garment workers. Ongoing research shows that no major brand can prove that all workers in their supply chain earn a living wage, whether fast fashion or luxury apparel. And raising worker wages just $100 per week (about what’s needed to reach a living wage in Bangladesh and India), would immediately cut 65.3 million metric tons of CO2 out of the global economy, according to new research. Paying workers more wouldn’t break the bank for brands either. One study shows that a living wage in India, for example, only adds 20 cents to the cost of a t-shirt.

Additionally, an estimated 80% of the garment makers in factories are female, compounding the labor violations and gender discrimination these workers face with forced overtime, lack of basic fire and building safety, no maternity leave, and unsafe travel to work. And the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these conditions. A new study from Traidcraft Exchange and the Modern Slavery and Human Rights Policy and Evidence Centre shows that in Bangladesh, Covid-19 inflamed existing vulnerabilities for women, including financial and housing insecurity, and increased exploitative practices like sexual and verbal abuse, mainly from line supervisors pushing garment makers to work faster to achieve unrealistic production targets. While many large brands have returned to profitability after the initial hit of the pandemic, their workers still feel the lingering effects.

To love garment makers as our neighbors, we must stop being indifferent to their needs and circumstances. After all, “the opposite of loving your neighbor is not always hating them, but just being indifferent to them” writes Jim Wallis. We must advocate for systemic change and protections for workers. Movements like this are gaining ground. In California, the historic Garment Workers Protection Act passed in 2021, which ended the piece-rate system of payment for factories producing goods in Los Angeles and holds brands accountable for wage violations in their supply chains.

Small, independent brands often lead by example. My own brand, Arrayed, partners with a women-owned, worker-led garment collective in Manila to bring our t-shirts to life. As a citizen, support locally made, small-batch production, conscious brands as often as possible or turn to thrift and resale. By consuming less and more mindfully, and advocating for garment workers’ rights, we can live out our faith with integrity.

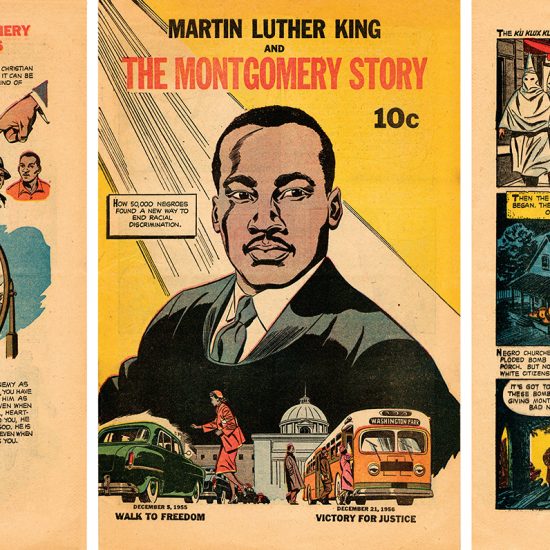

In his final sermon, Dr. King expounded on the story of the Good Samaritan saying, “I can imagine that the first question which the Priest and the Levite asked was: “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” Then the good Samaritan came by, and by the very nature of his concern reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” Let us follow the example of the Good Samaritan and advocate for our hidden neighbors, the garment workers.

Lizzy Case is a writer, theologian, and founder of Arrayed, a liberative people-first, planet-focused Christian apparel brand. She currently lives in southern California.