Is nothing sacred anymore, is forever just another word?

The rock star Meatloaf famously posed these questions. And we’re singing along with him, wondering if nothing is sacred anymore, after seeing how some politicians decided to treat Easter this year. Even the holiest day for Christians is now just another occasion for partisan diatribes and politicking.

Lest we should seem overly dramatic, remember that Easter defines us as Christians. As Pope Paul John II declared, “We are the Easter people and hallelujah is our song.” We both spent Sunday morning joining other Christians in celebrating the resurrection. It’s the key event that inspires our faith in Jesus, distinguishing him from a host of other failed messiahs who also died on Roman crosses.

(Bruno van der Kraan/Unsplash)

Yet, for some politicians, this past weekend was just another opportunity to bolster their own interests. From former President Donald Trump using “Easter” statements to sing his grievances against political opponents to Georgia Republican Senate hopeful Herschel Walker using the resurrection as a political attack to North Carolina Democratic Senate hopeful Cheri Beasley actually campaigning in church services on Easter.

Each of these politicians offered an example of how not to engage in the public square. They managed to profane the holiest of moments, attempting to transform a miracle only God can perform into a moment that benefits themselves and harms their opponents. If churches and Christians don’t stand up against abuses like these, we’ll find our shouts of “He is Risen!” co-opted and exploited for other kingdoms.

Thus, we cannot remain quiet — and let just the rock stars cry out, “Is nothing sacred anymore?” In this issue of A Public Witness, we report on three moments from this weekend when Easter hope was weaponized for partisan politics.

Festivus

The man who lost the 2020 presidential election released not one but a trinity of Easter messages on Sunday. But none of them showed any understanding of the occasion.

“Happy Easter to failed gubernatorial candidate and racist Attorney General Letitia James,” Trump said in one statement attacking the Black Democrat investigating Trump’s business dealings. “May she remain healthy despite the fact that she will continue to drive business out of New York while at the same time keeping crime, death, and destruction in New York!”

“Happy Easter to all including the Radical Left Maniacs who are doing everything possible to destroy our Country,” he wrote via his Save America PAC. “May they not succeed, but let them, nevertheless, be happy, healthy, wealthy, and well!”

His other statement, quickly buried by the tone of those two, wasn’t mean but also was pointlessly generic. If he swapped out the word “Easter,” it could’ve been offered for just about any occasion: “Happy Easter to all. May there be great peace and prosperity throughout the World!”

Trump seems to treat Easter like a Seinfeld rerun with the fake “Festivus” holiday, which the character celebrated as a Christmas alternative for the “airing of grievances.” For some, apparently one such holiday a year isn’t enough. But to treat Easter this way says more about the one releasing the statements than it does about the targets of his ire.

On one level, this shouldn’t surprise us. Trump’s long demonstrated he doesn’t understand or appreciate the meaning of Easter (and we don’t just mean in a “Two Corinthians” way). During the 2016 campaign, he appeared on ABC’s This Week on Easter morning but apparently wasn’t ready for the softball question: “What does Easter mean to you?”

“Well, it really means something very special. I’m going to church in an hour from now and it’s going to be, it’s a beautiful church,” he answered. “And it’s just a very special time for me. And it really represents family and get-together and something, you know, if you’re a Christian, it’s just a very important day.”

That’s akin to the student who doesn’t know a concept on a college exam but is determined to fill the essay space anyway in hopes of partial credit. And once he got into the White House, things didn’t get better. Easter often turned out to be just another day about himself.

“I did what was an almost an impossible thing to do for a Republican — easily won the Electoral College! Now Tax Returns are brought up again?” he tweeted on Easter in 2017. “Someone should look into who paid for the small organized rallies yesterday. The election is over!”

“This is a special year. Our country is doing great. You look at the economy; you look at what’s happening,” he declared during the 2018 White House Easter Egg Roll. “Nothing is ever easy but we have never had an economy like we have right now. And we’re going to make it bigger and better and stronger.”

Donald Trump speaks during the 2019 White House Easter Egg Roll in Washington, D.C., on April 22, 2019. (Andrea Hanks/Public Domain)

The next year, he talked about impeachment and why the country needed to build the wall. And just before heading to church that year, he tweeted about being the victim of “the worst and most political Witch Hunt in the history of the United States,” adding, “Disgraceful!” Yes, definitely a disgraceful Easter tweet.

Trump is notoriously self-centered. Because his statements reflect this character flaw and align with how he’s treated Easter in the past, the temptation is to overlook or dismiss his rhetoric as par for the course. Yet, as Christians, the true danger is growing dull to such affronts. God raising Jesus from the dead is a radical act of hope. We should fiercely defend the Church’s Easter message from those wanting to dull its implications. The way Trump used the occasion for self-aggrandizement, insulting his opponents, and revisiting grievances is offensive to those celebrating the miraculous act of a magnanimous God.

Help sustain the ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Out of Bounds in Georgia

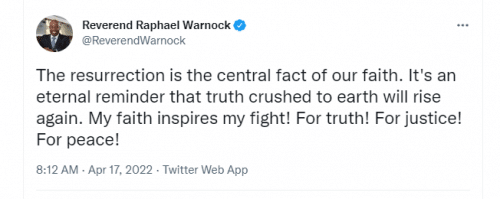

The Easter rhetoric in Georgia was no less elevated. GOP Senate candidate Herschel Walker, who brazenly campaigns in churches, used Holy Saturday — traditionally a somber day for Christians — to resurrect a year-old attack on his opponent, Sen. Raphael Warnock (who is also the pastor of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta).

Personally, we’ll acknowledge that Warnock’s tweet confused us. Making complex theological statements in a couple hundred characters on social media is a treacherous exercise. The biblical and historical complexities of what the resurrection entails involves interesting, but dense, discussions that rarely arise in sermons preached on Easter Sunday (and certainly not in the lyrics to contemporary Christian music sung in Easter worship).

Personally, we’ll acknowledge that Warnock’s tweet confused us. Making complex theological statements in a couple hundred characters on social media is a treacherous exercise. The biblical and historical complexities of what the resurrection entails involves interesting, but dense, discussions that rarely arise in sermons preached on Easter Sunday (and certainly not in the lyrics to contemporary Christian music sung in Easter worship).

Back in 2021, Warnock’s tweet became a religious Rorschach test. Reporting about the episode in the Washington Post, Michelle Boorstein noted, “For many conservative Christians, the tweet challenged the core belief of their faith: Jesus’s literal resurrection is the way to salvation. To many progressive and moderate Christians, Warnock seemed to be suggesting closeness to God is more about their actions, what they do to relieve suffering and create justice. The seeking of social justice is emphasized in particular in the Black church.” (The tweet in question was actually deleted after just a few hours and Warnock’s office said it was posted by staff and not by him.)

By intentionally revisiting the episode, Walker clearly intended to renew the controversy. Presumably, he thought attention and votes would come his way by challenging his opponent’s religious beliefs. The only reason for resurfacing the short-lived tweet was to paint his opponent as outside the mainstream of Christian belief, at least as understood by Walker. In doing so, Walker reduced the awe-inspiring power of resurrection to a political bludgeon.

Such cynicism about Easter deserves to be flagged for unsportsmanlike conduct. Not only does it diminish what Christians proclaim about resurrection, but it also demonstrates a confusion about politics. The theological beliefs of any candidate for public office are irrelevant (unless, of course, they conflict with the foundational principles of democracy itself). Good faith debates about the meaning of resurrection are part of the Christian life. They should occur in church sanctuaries, not in quests for a desk in the Senate chamber.

What Walker and Warnock have in common is that, before entering politics, both men gained professional notoriety for their performance on Sundays. While we deplore Walker’s tweet picking a partisan fight with Warnock about the implications of the empty tomb, we must also note that his antagonism towards a preacher with a doctorate in theology from a prestigious seminary is just silly. We’d be equally dismissive of Warnock challenging Walker in a 40-year dash, though that contest would be less threatening of democratic principles.

It’s also worth noting that this year Warnock kept things simple on social media. Not to be misunderstood, he called the resurrection “the central fact of our faith” and explained the role it plays in his life.

We doubt that tweet will show up in a Walker attack anytime soon.

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

Sunday Evangelism

Unfortunately, it’s not unusual for politicians to campaign during Sunday morning worship services, despite IRS rules that prohibit 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofits like houses of worship from engaging in partisan politics like that. Already this year, we’ve reported at A Public Witness how Herschel Walker is using this strategy in Georgia, and how former U.S. Congressman Mark Walker is aggressively campaigning in church services in North Carolina (including one where the church even played one of his campaign ads). We also urged other reporters to pay more attention to these campaign moments, and the Associated Press did just that by looking at how Ohio Republican Senate hopeful Josh Mandel is, as he put it, “running a campaign through churches.”

We hoped Easter would at least be off-limits. Sadly, the draw of the Easter crowds was just too tempting for at least one candidate.

Cheri Beasley, the presumptive Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate seat in North Carolina, spoke during not one but two Easter services. We previously noted in our piece about Mark Walker’s exploits in the Tar Heel race that Beasley was also speaking in churches. But Easter politicking takes this problem to another level.

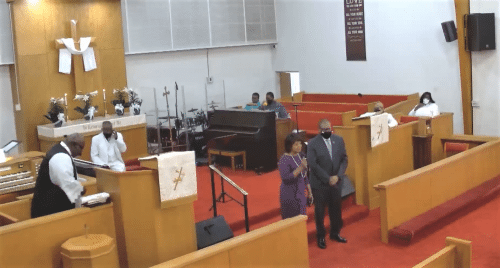

Beasley, former chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, spoke Sunday at both Trinity AME Zion Church and Mount Zion Baptist Church in Greensboro. We found the video of her remarks at Trinity, and it clearly violates both the IRS’s rules and good theology.

The candidate mentioned it was “truly a blessing” to be at the church for “Resurrection Sunday.” After greetings, she quickly launched into noting that she’s running for the U.S. Senate and recounted her qualifications and key issues.

“You all know what the issues are,” she said. “So many people as I travel across this state want to know that the next senator is going to fight to lower costs, make sure people have access to good, quality healthcare, clean air, clean water, the constitutional, foundational right to vote in North Carolina.”

“We need somebody who will lead with courage. We need somebody who is a woman of faith. We need someone who will stand by the truth,” she added. “I am asking for your prayers and your support. The primary election is May 17. The general election is Nov. 8.”

Screengrab as Cheri Beasley (in purple) speaks at Trinity AME Zion Church in Greensboro, North Carolina, on April 17, 2022.

Urging people to vote because “we’ve got to change things,” Beasley argued “this election is about today but it’s about the next generation. It is about righting the ship right now in the name of Jesus.”

After her remarks, the pastor commented about the importance of voting before trying to shift the focus back to the good news proclaimed on that first Easter. But the whole moment between hymns about Jesus the risen Savior seemed off-key. While we don’t think candidates should be campaigning during church services on any Sunday, we find it particularly problematic for a candidate to interrupt shouts of “He is Risen!” with “Vote for Me!”

Individually, each of these moments — Trump’s petty complaints, Walker’s weaponizing of theology, and Beasley’s sanctuary politicking — is concerning. But together they reveal that when politics becomes our idol, even our holiest moments, like Easter, become campaign events.

We also fear these three incidents provide a warning that the political co-opting of our sacred spaces and symbols is getting worse. We must demand better. We need politicians to declare, “I would do anything for voters’ love, but I won’t do that.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood