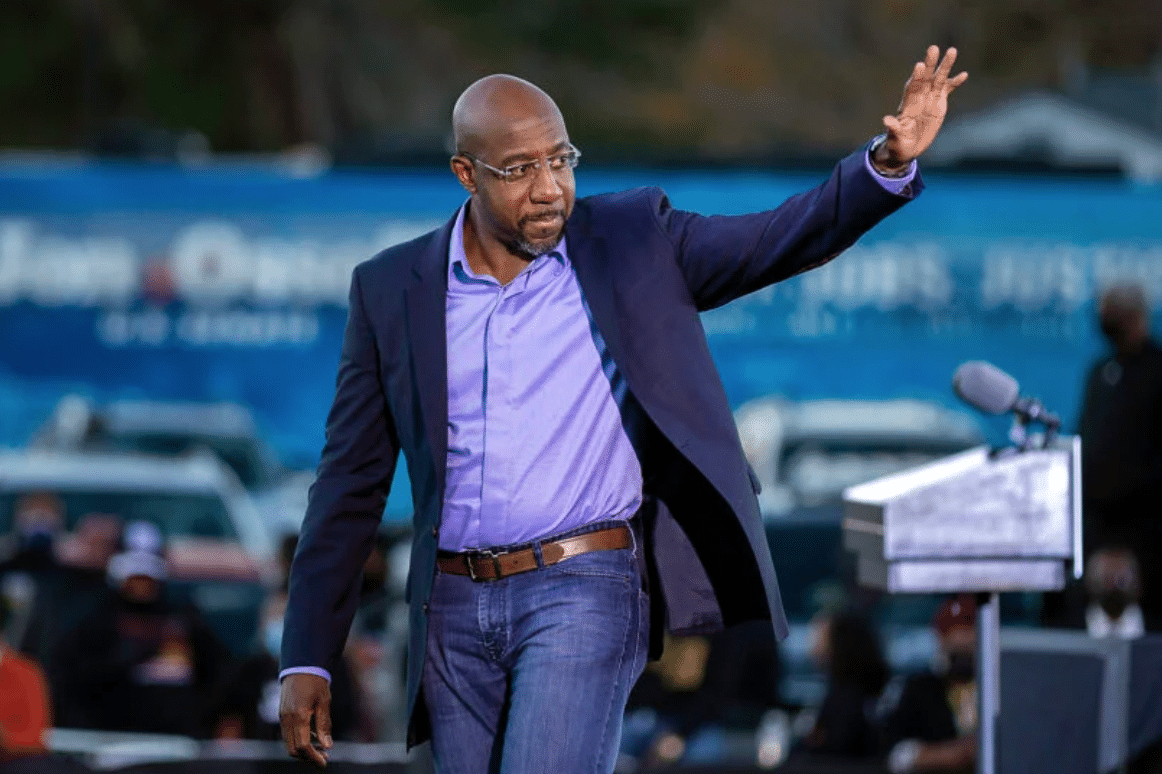

Democratic U.S. Senate candidate the Rev. Raphael Warnock waves to supporters during a drive-in rally Jan. 3, 2021, in Savannah, Georgia. Vice President-elect Kamala Harris made a campaign stop for Georgia candidates Warnock and Jon Ossoff before the runoff election Tuesday. (AP Photo/Stephen B. Morton)

(RNS) — Sen. Raphael Warnock may have added a title to his name when he was elected to the U.S. Senate last year, but he says he remains first and foremost a preacher.

“It was disruptive for me to decide to run for the United States Senate,” he said in an interview ahead of the Tuesday (June 14) release of his book, “A Way Out of No Way: A Memoir of Truth, Transformation, and the New American Story.” “I enjoyed being a pastor, and, in my heart, that’s who I am essentially — not only a pastor but the son of two pastors.”

Born in Savannah, Georgia, the 11th of 12 children of those two pastors, both Pentecostals, Warnock took his book’s title from a familiar refrain in Black churches.

“It is an expression that’s born of suffering and travail and yet keeping the faith even in the midst of challenge and recognizing that the light shines in the darkness. Not that there isn’t darkness in the world. But the light shines in the darkness and the darkness overcometh it not,” Warnock said, quoting the Gospel of John.

He went on to serve or pastor churches in Birmingham, Harlem and Baltimore, rising eventually to senior pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached.

Warnock, the 11th Black senator in American history, said his efforts on Capitol Hill, such as seeking to expand access to Medicaid and cap the cost of insulin, are based in the suffering he has seen.

“I do this work because I preach, after all, every Sunday morning in honor of a man who spent much of his ministry healing the sick, even those with pre-existing conditions,” he said, referring to Jesus. “I believe that health care is a human right. And it is certainly something the wealthiest nation on the planet ought to provide for all of its citizens. I intend to keep fighting for that.”

Warnock, 52, spoke with Religion News Service about the influence of King on his life, the challenges of being a father to young children from afar and how he finds sermon topics as he works in Washington.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In your book you wrote that you initially tried to sound like Martin Luther King Jr. when you preached but eventually found your own voice. How have you found your voice on the Senate floor?

The voice and the moral vision of King absolutely captivated me as a kid. He’s been formative for my understanding of what it means to make your faith come alive in the public square. I was inspired by his courage and his ability to move others to lay it on the line, put their bodies in the struggle in the hope of creating positive change.

All preachers, like singers, start out imitating somebody, and, in the course of that, hopefully you find your own voice. Through decades of preaching, I’ve tried to find mine, both as a pastor and as an activist and now as a senator. I’ve tried to bring the same kind of conviction and commitment to the issues that I argue about on the Senate floor, which I think are moral issues: voting rights, health care, a whole range of issues.

Is there a way to sum up how you juggle your roles as pastor, politician and father?

I’m a father, and I’m a pastor, and I bring my love for my children to this work as a senator. I want to make sure my children are left with a country and a planet that is both sustainable and characterized by peace and justice. In order for my children to be OK, other people’s children really need to be OK. So it’s difficult when I’m away from them, days at a time, but we talk on FaceTime, and we make it work, and they inspire me to keep on pushing.

Have your congressional colleagues sought you out for your pastoral assistance?

I’m certainly available for that. Occasionally, I have colleagues on both sides of the aisle with whom I seldom vote in agreement ask for prayer. Or they’ll say, “Rev, pray for me.” They’ll ask me what the sermon’s about this Sunday. I’m happy to talk about that. But in this moment, what we need is people who bring us together.

You’ll soon be on the Georgia ballot again. At Ebenezer, you worked with Black churches on Souls to the Polls, an initiative that has been eliminated in parts of your state. How will you approach the election this time out?

Early voting is still very much available. I intend to do everything I can to encourage people to exercise their constitutional right to vote. And I hope faith communities everywhere — not just Black, but white sisters and brothers, not just Christians but Jews and Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs — will dig into the wellsprings of their own faith traditions, as those traditions center the values of justice and compassion and beloved community, and that will drive them out to the polls.

A vote is a kind of prayer for the kind of world we desire for ourselves and for our children, and I think our prayers are stronger when we pray together.

How do you prepare for your Sunday sermons? Is it harder to do with your senatorial responsibilities?

Oh, there’s sermons all around us. You just have to be attentive to the lessons that life is trying to teach us and where the Spirit is trying to take us. John Lewis, who was my parishioner, started out thinking that he was going to be a preacher. But instead of preaching sermons, he became a sermon. That’s the work I try to do, whether I’m standing on the Senate floor or standing in the pulpit or standing on the streets, arguing and fighting for Medicaid expansion or criminal justice reform or voting rights. I’ve tried to live and be the sermon. I think that’s what makes preaching come alive on a Sunday morning.

You mentioned being inspired to observe a morning devotional time after hearing your mother’s whispered prayers early in the day. Are you continuing that practice? And if so, what Bible verse or verses did you focus on today?

Prayer is very central and so very important for my life, and I — including this morning — I tend to take a look at the lectionary texts for the week, and often I begin there. We, of course, are on the heels of Pentecost. And what I’ve tried to do in my ministry is to be open to the winds of the Spirit.

Do you have a preference for how you are identified? Reverend Senator? Senator Reverend Warnock?

I don’t care what you call me. Just call me when it’s time for dinner. My Mama named me Raphael.

Raphael and Gamaliel, your middle name, are both biblical. Is that a heavy burden for you?

No. It has always been a part of my self-understanding. Raphael, one of the archangels — I don’t know if I was angelic as a kid. I’m sure I got in my share of trouble like any other kid. But the name means “the Lord heals.” And my hope in this moment in our country, in which there’s so much division, is to be a source of healing, an agent of healing. We certainly could use it in the Senate.