The sun sets behind a pumpjack at an oil well. Photo by Zbynek Burival/Unsplash/Creative Commons

(RNS) — A prominent mainline Christian denomination plans to divest from five oil companies it believes are not doing enough to address climate change.

The vote to divest from Chevron, Exxon Mobil, Marathon Petroleum, Phillips 66 and Valero Energy comes after years of debate in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

On Wednesday (July 6), commissioners at the PCUSA’s general assembly voted 340-41 to add those companies to the denomination’s divestment list. They join 85 other companies on the list — most with ties to the military or the weapons industry.

The move “gives teeth to selective divestment,” said Aaron Ochart, vice moderator of the Environmental Justice Committee, who introduced the divestment recommendation to the general assembly, which voted online.

Since the 1980s, Presbyterians have called for a move away from fossil fuels, including oil. More recently, they have debated whether to divest or to use their investments to pressure companies to change their ways. In 2016 and 2018, votes to divest failed in favor of more engagement.

Rob Fohr, director of faith-based investing and corporate engagement for the PCUSA, said the church’s “Mission Responsibility Through Investment” committee had hoped to see more change at the five oil companies.

But their efforts at engagement failed to make progress, he said.

“Divestment is never the goal,” he said in an email. “Corporate change is the goal. MRTI determined, after engagement with these five companies, that continued engagement is not likely to yield meaningful change. Meanwhile, the climate crisis is only increasing in urgency. We hope this divestment will be received as a clear signal that meaningful change is needed.”

The next step in the process will be for the MRTI committee to compile a new version of the divestment list. That list will then be sent to the denomination’s pension board and the Presbyterian Foundation for approval. Both groups have already said they will approve the new list, said Fohr.

During the discussion of the divestment recommendation, Tom Taylor, president of the Presbyterian Foundation, was asked about the financial impact of divesting. He said the impact was “impossible to know” and would depend on future market conditions. He also said the foundation would act quickly to divest.

“As soon as possible, we will get out of it,” he said.

Commissioners, who are made up of local Presbyterian church leaders, also approved a recommendation to add seven other companies, including three airlines, for more direct engagement. Those companies are found on a list compiled by the environmental group Climate Action 100, according to the denomination’s Environmental Justice Committee.

Those commissioners also approved a proposal, known as an overture, to create a “Presbyterian Tree Fund” to purchase carbon offsets for work-related air travel by church staff, as well as one titled “Investing in a Green Future.”

Earlier this week, a group of three dozen faith groups from seven countries announced they have divested from fossil fuels. The groups include five Church of England dioceses, two Catholic dioceses in the United Kingdom, 11 Catholic religious orders, two Jesuit universities in the United States and the United Methodist Church in Ireland.

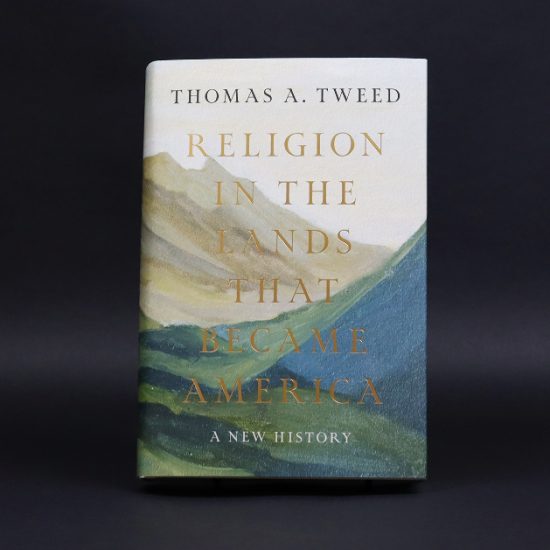

Darren Dochuk, author of “Anointed With Oil,” a history of religion and the oil industry in the United States, said faith groups in the past saw oil and other fossil fuels as a blessing. Some of the early oil tycoons, such as the Pew family and Lyman Stewart, who helped fund the fundamentalist movement, were Presbyterians and many church institutions in the United States were funded by oil money.

Divesting from fossil fuels, Dochuk said, is complicated both for denominations and for local congregations, especially those in areas where the local economy depends on the fossil fuel industry.

“Today’s generation probably doesn’t realize that this is a relationship generations in the making,” he said. “So, to all of a sudden unravel it or disassemble it is complicated.”

Fletcher Harper, an Episcopal priest and executive director of GreenFaith, an environmental group, said the increasing threat of climate change makes divestment from fossil fuels a crucial priority for churches. In the past, he said, there were worries that doing so would cost churches money.

That’s no longer the case, he said.

“The research has shown you can get out of oil and gas and perform as well as the market,” he said.

Along with divesting, he said, faith groups can work with other activists to put pressure on financial companies to get out of investing in fossil fuels. That’s the bigger goal, he said.

“The purpose of the climate movement is not just to get certain small sectors of the economy to be fossil fuel-free,” he said. “We need a fossil-fuel-free economy, period.”

Fohr told Religion News Service in an interview that the MRTI committee will continue to engage with companies and work with church leaders to turn their values into action. The work remains complicated, he said, adding that “the divine is in the details.”

Still, he sees the divestment vote as a step toward progress.

“Fossil fuel divestment has been one of the more divisive and controversial issues at the past few General Assemblies,” he said in an email. “This year, it passed by almost 90% of the vote. I think this is something the PCUSA has to offer to the broader culture — through robust and transparent processes, differing sides can come together to effect meaningful change.”