People pray over an individual. Photo by Adrianna Geo/Unsplash/Creative Commons

This story is part of a series on disability and faith.

(RNS) — The worship service begins with “Amazing Grace,” an old favorite with the lyrics: “I once was blind, but now I see!”

Later, preaching on the gospel story of Jesus healing a blind man, the pastor preaches a sermon about Jesus bringing wholeness to the physically and spiritually broken, followed by a rendition of the Hillsong Music worship ballad “The Lost Are Found.” The congregation members raise their hands as they sing, “The lost are found, the blind will see, the lame will walk, the dead will live!”

Imagine being a person with a disability at this hypothetical but unremarkably common service. Even if a worship space has ramps, accessible seating, large-print programs and a separate room for those feeling over stimulated, the theology of many Christian services itself can offer little besides condemnation and exclusion.

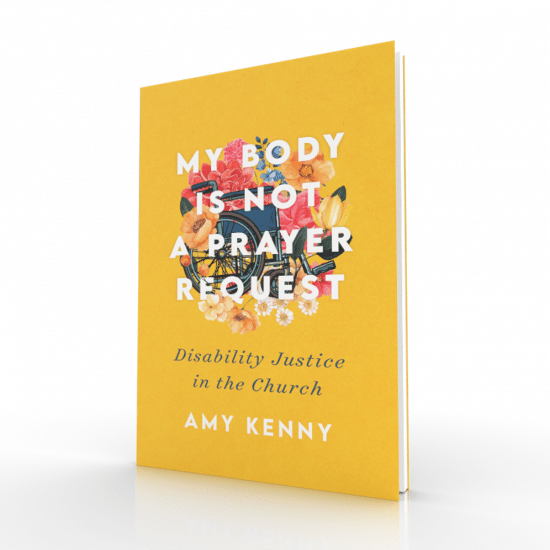

“When we limit our understanding of faithfulness or of holiness to nondisabled people,” said Amy Kenny, a Shakespeare scholar and author of “My Body Is Not a Prayer Request,” “it limits our understanding of God, and it allows for us to be fooled into thinking that independence is a virtue, and non-disability is somehow holy, or good.” This might be termed “theological ableism.”

Kenny knows this firsthand. For most of her tween and teenage years, churchgoers would routinely attempt to “pray away” her disability on Sundays. Kenny acknowledges that the prayers were well-meaning, even as they labeled her as defective.

Kenny thinks about her disability differently: It can be a way to reveal God to others.

“These unsolicited prayers come from a place of wanting to erase disability altogether. They fail to recognize that disabled people are at the forefront of the work that God is doing in and with humanity throughout Scripture,” Kenny said.

She listed Moses, Elijah, Timothy, Zacchaeus, Paul and Jesus himself as just some of the often-overlooked disabled biblical characters. Their prominence in scripture shows us that all humans have divine worth, Kenny said.

In her new book, Kenny also writes about her belief in a disabled God — one who returned from the dead with a scarred body, and who is described as sitting on a throne with wheels, not unlike her own wheelchair. She originally encountered the idea in Nancy Eiesland’s book “The Disabled God,” published in 1994.

“It just made such complete sense to me. It’s like when someone gives you the language to explain something you felt in your gut all along,” she said.

While conceiving of God as disabled is empowering for some, non-theistic religions also have beliefs that enrich followers’ understanding of disability. When she suffered a spinal injury as a 17-year-old, Vidyamala Burch did not identify as spiritual. It was only when a hospital chaplain led her in a brief meditation when she was hospitalized with complications related to her injury that she discovered another side of her disability.

“This experience of meditation and my subsequent exploration completely changed the direction of my life,” Burch, now in her 60s, wrote in an email. Today, she is a member of the Triratna Buddhist Community and is co-founder of Breathworks, an organization that offers mindfulness-based pain management. She pointed to a Buddhist teaching called the Sallatha Sutta, which imagines two arrows: One signifies physical pain, and the other mental suffering.

“(I)f someone has freed their mind, they will still be pierced by the first arrow as that is an inevitable part of life,” Burch explained. “But we can learn to let go of automatic resistance and resentment and then we are not pierced by the second arrow.” That teaching has been invaluable to Burch as a person with disabilities living with chronic pain.

Noor Pervez, a disability activist and community organizer, said his religious beliefs shape his commitment to disability justice. A board member of Masjid al Rabia, an Islamic community center for marginalized Muslims, Pervez annually hosts #MyDisabledRamadan, a series of online events where disabled Muslims share their varied experiences with Ramadan and discuss accessibility in Muslim spaces. Pervez is also on a team developing an Easy Read Quran designed for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“I think really critically about the fact that Islam has built-in accessibility modifications by default, around the things they knew of in the time the Quran was transcribed,” Pervez told RNS. “For example, modifications to allow people to pray while seated or lying in bed are readily available.”

Rabia Khedr is CEO of DEEN Support Services, a Canadian disability support organization founded by disabled Muslims. In her approach to disability theology, she draws on a story about the Prophet Muhammad. Abdullah Ibn Umm-Maktum, who was blind, approached the prophet as he was speaking to nobility in the mosque in Mecca. Muhammad turned away and frowned, Khedr said, but was quickly rebuked by Allah.

“After that, the prophet always referred to Ibn Umm-Maktum as the ‘man for whom I was rebuked.’ And, in fact, gave him high respect and honor and at some point made him in charge of the city of Medina in his absence,” said Khedr, who noted that if the prophet can shift his view of community members with disabilities, so can Muslims today.

Rabbi Michael Levy, who leads a disability empowerment organization called Yad HaChazakah, and who, like Khedr, is blind, noted that God chose Moses to lead the Israelites from Egypt, even after Moses protested that he was too “heavy of tongue and heavy of speech.”

“God said, ‘Don’t tell me that I can’t choose you because you have a disability,” said Levy, paraphrasing. Moses came to rely on his brother, Aaron, in the same way that disabled folks often rely on speech augmentation devices and other aids.

Once you begin looking for them, stories about disabled folks are woven throughout countless religious traditions. The teachings about disability they lead to, however, are often overlooked or oversimplified.

Bethany McKinney Fox is the founding leader of Beloved Everybody, a Los Angeles community for people with and without intellectual disabilities. She said many Christians reduce healing narratives, like the story of blind Bartimaeus in the Gospel of Mark, to be about a miraculous cure. The reality is more complicated, she insisted, pointing to the shift in Bartimaeus’ community and Jesus’ decision to ask Bartimaeus whether he wants his sight restored.

“His eyes are cured at the end of the story. But he also becomes a follower of Jesus, and the crowd is transformed,” McKinney Fox observed. “If you just narrow it down to, ‘Bartimaeus was blind and then he wasn’t,’ you miss a host of other things happening here.”

Ultimately, the stories faith traditions tell about disability matter because they translate into action. Stories that dehumanize disabled folks label disabled people as the problem, rather than the barriers to accessibility themselves.

Lamar Hardwick, author of “Disability and the Church” and pastor at Tri-Cities Church in East Point, Georgia, said faith communities should place disabled folks at the center of their ministry.

“Jesus places the emphasis on starting with the disability community, making them the priority at this banquet, which can be an allegory for the church,” said Hardwick, referencing Luke 14. “The challenge we have in the Western church is, we built the church backwards. We think about disabled folks last, when Jesus tells them to focus on them first.”