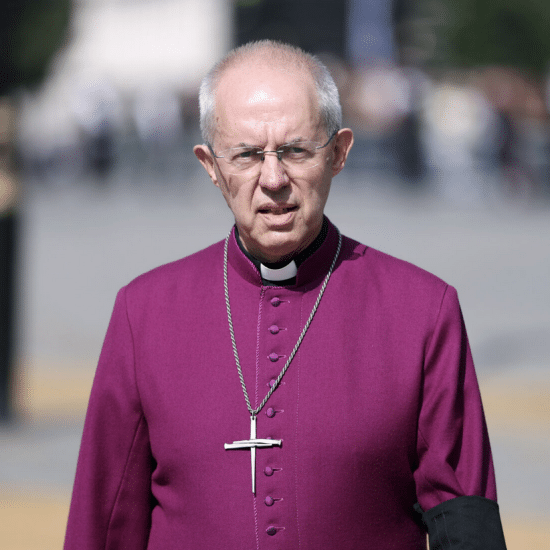

The official portrait of Queen Elizabeth II in 2011 as the Australian sovereign. Photo courtesy of Queensland/Wikipedia/Creative Commons

LONDON (RNS) — Elizabeth II of England, Britain’s longest-serving monarch and official head of the Church of England, died Thursday (Sept. 8) at Balmoral Castle in Scotland at age 96. She came to the throne in 1952 but had dedicated her life to service of her nation six years earlier, as a 21-year-old princess, saying, “God help me to make good my vow.”

When Elizabeth was crowned, following her father, George VI, Britain was still recovering from World War II and its heavy bombing campaigns; Winston Churchill was prime minister and the country still had an empire. The young queen’s coronation suggested a new era — as the millions of television sets purchased to watch the live broadcast of the ceremony from London’s Westminster Abbey signaled.

But the coronation itself was steeped in tradition and confirmed the monarchy’s intertwining of the monarchy and religion. The more-than-1,000-year-old ceremony involves the anointing of the monarch, who commits himself or herself to the people through sacred promises.

One of those, to uphold the Protestant religion, is also a reminder of the religious divisions of the nearer past.

The queen’s two titles of Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England, given to her at her accession, also owe their existence to Reformation history. The first was first bestowed on Henry VIII by a grateful pope for the king’s rebuttal of the teachings of Martin Luther. Henry defiantly held onto it even after breaking with Rome to declare himself head of the new Church of England.

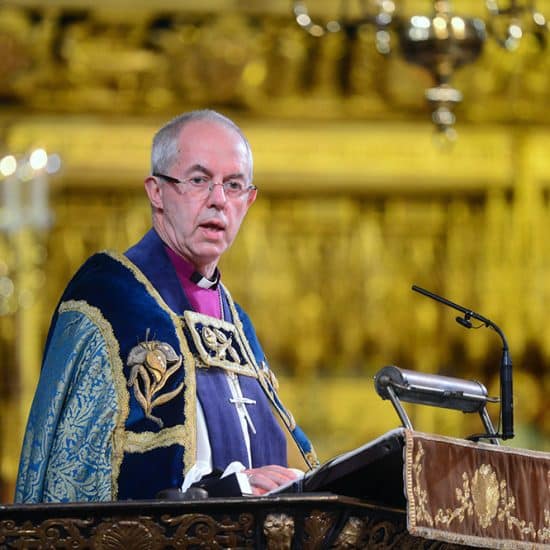

His daughter, the first Elizabeth, dubbed herself Supreme Governor of the Church of England, saying Jesus Christ was its head. To this day, the British monarch retains constitutional authority in the established church but does not govern it. The modern Elizabeth left that to the bishops, although she addressed general synods and maintained a role as a listener and guide to her primate, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

But while Defender of the Faith has been an inherited title and little more, Elizabeth II embraced it and in recent years made it her own, speaking very openly about her faith and explaining how it provided the framework of her life.

She did this mostly through her annual Christmas message, a tradition begun by her grandfather, George V, in 1932, and continued by her father. Her early Christmas Day broadcasts were platitudinous — the holidays as an occasion for family was a frequent theme. In 2000, however, she spoke of the millennium as the 2,000-year anniversary of the birth of Jesus Christ, “who was destined to change the course of our history.”

She went on to speak very personally and frankly about her faith: “For me the teachings of Christ and my own personal accountability before God provide a framework in which I try to lead my life. I, like so many of you, have drawn great comfort in difficult times from Christ’s words and example.” Similar sentiments have been aired at Christmas ever since.

The queen led the nation at regular services honoring the war dead, or offering thanksgiving for her jubilees, but worship was not, for her, only a public show. She attended church regularly throughout her life and is said to have had an uncomplicated, Bible- and prayer-book-based faith.

That love of the Bible was something she shared with American evangelist Billy Graham, whom she invited to preach for her on several occasions (though the close friendship the Netflix series “The Crown” suggested between them seems far-fetched). She relied on the deans of Windsor — the clerics who run St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, where Prince Harry and Meghan Markle married — for spiritual solace.

Her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, who died in April 2021, and her son Charles, who succeeds her, always displayed a more intellectual curiosity about religion, including a great interest in both other Christian denominations and other faiths as Britain’s religious landscape became increasingly diverse.

Elizabeth expressed an increasing openness as well. She encouraged members of all faiths to be present at great church occasions and in the annual Commonwealth Day service held at Westminster Abbey. She met five popes — a remarkable turnaround for a monarchy that once broke so spectacularly from Rome — though she never went so far as to ask other religious leaders to be a chaplain or offer other spiritual advice.

There has been talk of disestablishment of the Church of England, even in Anglican circles, although there has been little call for this from other faiths. But Elizabeth’s views seemed apparent when the queen spoke at Lambeth Palace in 2012, suggesting the Church of England might act as a sort of umbrella under which other faiths might shelter, saying Anglicanism “has a duty to protect the free practice of all other faiths in this country.”

At her Platinum Jubilee thanksgiving service at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, in June, Buddhist and Jewish leaders were present alongside Anglicans and other Christians.

Many figures of faith and the church will be among the dignitaries paying their respects at her lying in state at Westminster Hall and at her funeral at Westminster Abbey. According to plans outlined in Politico in 2021, she will be buried in the King George VI Memorial Chapel at Windsor Castle, outside London, after an Anglican service at St. George’s Chapel there.

(This article is adapted from an earlier profile that appeared in June 2022.)