With Christmas approaching, the story of Jesus’ conception and birth, popularly known as “the Christmas story,” vies for our attention once again. Most versions of the Christmas story are produced by combining select episodes from chapters one and two of the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. From Christmas storybooks to Christmas pageants, the most common starting point is the appearance of the angel Gabriel to Mary, recounted in Luke 1:26–38.

Christine Trotter

What happens next in Luke, however, is usually omitted: Mary travels from Nazareth to Judea to visit her relative Elisabeth, an older woman who speaks prophetically to Mary and informs her that she is pregnant with the Lord (1:39–45). Christian parents and educators need new renditions of the Christmas story that include Elisabeth and acknowledge her prophetic insight. Here is what we know about Elisabeth, why her character is frequently left out of the Christmas story, and why she should be included.

Within Christian tradition, Elisabeth is primarily remembered as a barren woman who, as the result of God’s favor, conceived in old age and became the mother of John the Baptist (Luke 1). Elisabeth is also conceptualized as an encouraging older woman who supported Mary, her younger relative, during her pregnancy with Jesus. These portraits of Elisabeth are not wrong, but they are incomplete.

As Luke recounts Elisabeth’s interaction with Mary in 1:39–55, Elisabeth functions as a prophet, that is, a person used by God to reveal supernatural knowledge to others. The first indication that Elisabeth acts as a prophet is that she is “filled with the Holy Spirit” (1:41) prior to speaking. The second indication is that Elisabeth knows things in 1:42–45 that she could not have known from her own experience. Elisabeth immediately declares that Mary is “blessed among women” and pregnant, even though Mary had no signs of pregnancy and no chance to tell Elisabeth about the angel’s words to her (1:39–42). Furthermore, Elisabeth recognizes that “the fruit of [Mary’s] womb” (1:42) is no ordinary baby, but her “Lord” (1:43). Elisabeth knows Mary had trusted the angel’s words would come to pass before Mary even has the chance to mention the angel to Elisabeth. She blesses Mary on account of her faith, saying, “blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by the Lord” (1:45).

Elisabeth’s prophetic power is underscored by the way Luke carefully scripts his narrative to convey that Mary was not visibly pregnant when Elisabeth joyously declared her to be “the mother of my Lord” (1:43). Elisabeth was six months pregnant when the angel appeared to Mary in Nazareth (1:36). After Mary stayed three months with Elisabeth, Elisabeth gives birth (1:56–57). Because pregnancies last nine months, there is no room in Luke’s story for Mary to linger in Nazareth for months and arrive at Elisabeth’s house already advanced in her pregnancy. Rather, shortly after her encounter with the angel, Mary set out “with haste” from Nazareth to Judea to see Elisabeth (1:39). In the tight chronology of Luke’s story, the reader is to assume that Mary would have arrived before she had even missed a period.

But couldn’t Mary have just told Elisabeth everything when she arrived, such that Elisabeth didn’t need supernatural insight to bless Mary and the fruit of her womb? No. There is no space in Luke’s narrative for Mary to tell Elisabeth about her conversation with Gabriel before Elisabeth blesses Mary and her unborn child. Luke emphasizes that Mary had only entered the house and greeted Elisabeth prior to her prophetic utterance (1:41). Upon Mary’s greeting, both Elisabeth and her son John are filled with the Holy Spirit, moving John to leap “for joy” in the womb and Elisabeth to prophesy (1:41–45). John’s prophetic action in utero fulfills the promise given to his father, Zechariah, that John would be “filled with the Holy Spirit even from his mother’s womb” (1:15–16). By divine insight, Elisabeth makes clear to Mary that God’s promise that she would conceive a son (1:31) has already been fulfilled (1:39–45). This realization causes Mary to burst into praising God (1:46–55). Christian tradition tends to remember that Elisabeth was the mother of a prophet while forgetting that Elisabeth was also given the power of prophecy at a pivotal moment in Mary’s pregnancy.

Why is Elisabeth so often omitted from the Christmas story? For versions of the Christmas story that begin with the journey to Bethlehem recounted in Luke 2, Elisabeth’s absence is a consequence of starting the story at the end of Mary’s pregnancy, just before Jesus is born. The Revised Common Lectionary, for example, designates Luke 2:1–20 alongside John 1:1–14 as the Gospel readings for Christmas Eve and Christmas. For renditions of the Christmas story that begin with Gabriel’s appearance to Mary in Luke 1, a practical need to simplify the story for young audiences seems to be the reason for eliminating Elisabeth’s character from the plotline.

Consider The Christmas Story by Jane Werner, A Little Golden Book that was first published in 1952 and is still in print today. After narrating the angel’s appearance to Mary, Werner proceeds directly to her marriage to Joseph and their journey to Bethlehem, omitting the episode of Mary’s encounter with Elisabeth completely. The Christmas Story by Ruth J. Morehead, which has sold over 1.5 million copies since its publication in 1986, likewise glosses over Mary’s pregnancy and her stay with Elisabeth. Following the angel’s appearance to Mary, which Morehead notes, “made Mary very happy,” Morehead writes, “Not long after, Joseph and Mary had to travel to Bethlehem to pay their taxes.” By omitting Mary’s journey to Judea and stay with Elisabeth, Werner and Morehead achieve streamlined narratives with a consistent focus on Mary, Joseph, and Jesus. They are, after all, writing children’s books, and simplifying complex stories is necessary for children’s books.

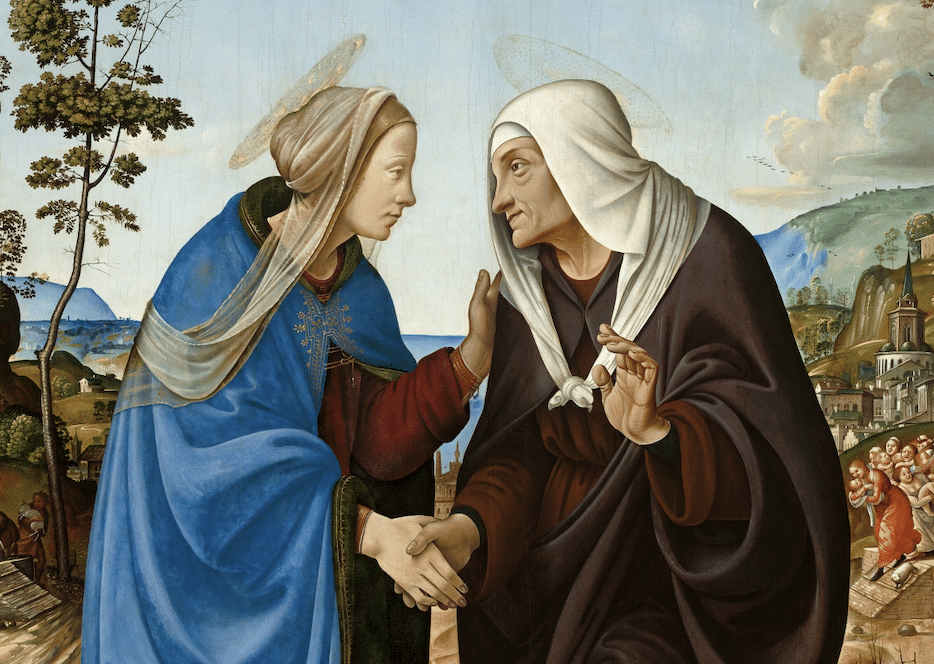

Mary and Elisabeth are depicted in a 15th-century oil painting by Piero di Cosimo. The title of the painting is “The Visitation with Saint Nicholas and Saint Anthony Abbot.” (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection)

Simplify we must, yet cutting Elisabeth out of the story comes at the cost of eliminating the voice and contribution of one of the few named women in the Gospels. Jane D. Schaberg and Sharon H. Ringe demonstrate that in the Gospel of Luke, named men outnumber named women by more than thirteen to one. Furthermore, women’s speech is seldom reported in Luke in comparison to men’s speech. These patterns in Luke reflect the relative scarcity of named women whose speech is recorded in the Bible as a whole. The first two chapters of the Gospel of Luke are an exception to the rule in featuring three named women (Mary, Elisabeth, and Anna), two of whom are quoted at length (Mary and Elisabeth). Because women’s voices are conspicuously absent in large portions of biblical narratives, it is important to recognize the women’s voices that are present. If we applied this principle to the Christmas story, we would include Elisabeth and direct our energies to making her character accessible for the intended audience of our retellings.

What might it look like to include Elisabeth in the Christmas story? To start, Christian educators should problematize the common understanding of Elisabeth as merely the mother of a prophet by acknowledging Elisabeth’s own gift of prophecy. A considerable number of illustrations of Mary and Elisabeth in Christian art implicitly deny Elisabeth’s prophetic power by depicting Mary as obviously pregnant in conversation with her. See, for example, La Visitation by Josse Lieferinxe, which represents Mary as practically full-term. Images like this communicate to viewers that both Mary and Elisabeth would have known about Mary’s pregnancy, no divine insight required. Once Elisabeth’s function as a prophet is ignored or denied, interpreters can reduce her role vis-à-vis Mary to that of an older pregnant kinswoman who congratulated and encouraged Mary during her own pregnancy. Christian educators and parents can do better. Here is my own suggestion for how one might include Elisabeth in the Christmas story this year:

Astounded at what the angel had told her, Mary packed her bag and set out on a journey to see Elisabeth. The angel had said that Elisabeth was in the sixth month of her own remarkable pregnancy — maybe she would understand. When Mary arrived, something miraculous happened. Before Mary could even tell Elisabeth about the angel, Elisabeth told Mary she was especially blessed and pregnant with the Lord! Somehow, Elisabeth already knew about the angel and that Mary had trusted that God would fulfill his promise. Mary was amazed to hear that she had conceived and celebrated with Elisabeth. Later, Mary asked Elisabeth, “How did you know?” Elisabeth replied, “When I heard your voice, my son leaped in my womb. The next thing I knew, I was filled with the Holy Spirit, and God told me what to tell you.” After staying three months with Elisabeth, Mary returned to Nazareth.

When Christian parents and educators decide how they will tell the Christmas story to the next generation, they have a choice to make. Do they want to perpetuate the exclusion of Elisabeth from the Christmas story or include her as a prophetic voice? Too many generations of Christian children have grown up with hardly any awareness of the women who followed Jesus and contributed to the early church. The Christmas story presents an opportunity to begin to correct this imbalance by introducing young people to Elisabeth, a prophetic pregnant mother who has been omitted from popular retellings of Jesus’ conception and birth story for too long.

Christine Trotter holds a Ph.D. in Biblical Studies from the University of Chicago and regularly teaches college courses on Religion and Gender.