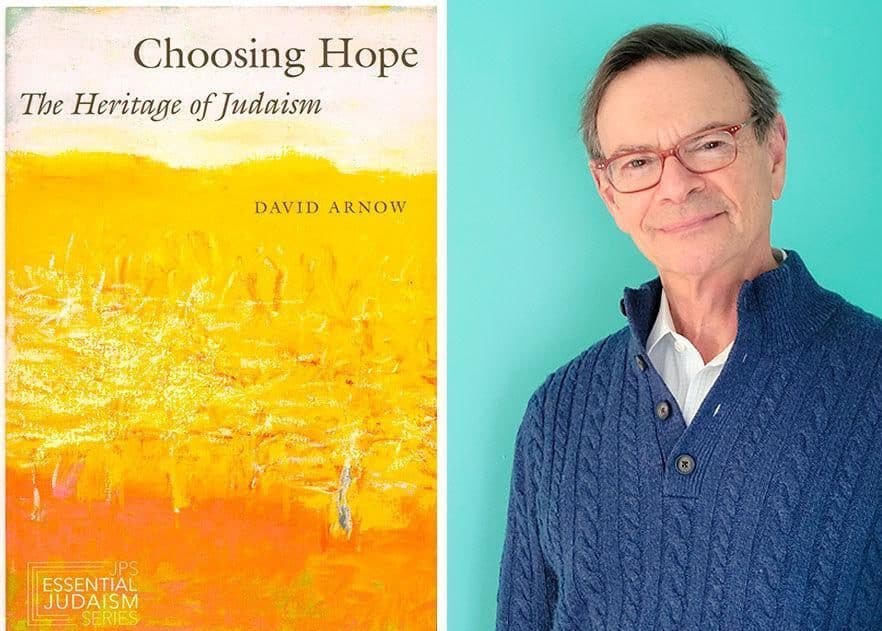

CHOOSING HOPE: The Heritage of Judaism. (JPS Essential Judaism Series). By David Arnow. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2022. Xxv + 320 pages.

As a Christian, I believe it’s important that I regularly acknowledge my tradition’s origins in ancient Judaism. While Judaism has evolved/changed/developed greatly over the centuries, sometimes in reaction/response to developments within Christianity, there is still much for Christians to learn from our spiritual ancestors and their contemporary descendants. There are, after all, many similarities and points of contact between the two traditions that can enrich the Christian faith if we’re willing to consider and acknowledge them. That has been my personal experience over the years. My Jewish friends and colleagues have taught me much that has enriched my own faith experience.

Robert D. Cornwall

I offer this personal preface to this review of David Arnow’s book Choosing Hope: The Heritage of Judaism, which forms a part of the Jewish Publication Society’s Essential Judaism Series because I found Arnow’s book to be theologically enriching and hope-producing. In writing this book, Arnow wants the reader to know and understand that hope stands at the center of Jewish theology. That’s understandable since Judaism, historically, has had to navigate tremendous challenges when it comes to its survival. Unfortunately, one of the biggest impediments to the survival of the Jewish community has been people/communities/nations that claim to be Christian. As a Christian, I know this to be one of the biggest stains on Christian history.

The author of this Choosing Hope, David Arnow, is by training a psychologist. He is also a scholar who has focused his attention on the Passover celebration. As such he has written widely on the Passover and how it might be celebrated along with exploring other elements of Jewish life, some of which have been directed at an interfaith audience. In this book, the focus is on Jewish understandings of hope and why hope matters to being Jewish.

In his introduction, Arnow sets the tone of the book by defining hope as that which “reflects our embrace of the possibility of a particular, deeply desired future, and hope fuels our actions to help bring it about” (p. xiv). He suggests that hope is not the same thing as faith. While faith is an unshakeable belief, perhaps belief in God or the goodness of humanity. That faith serves as the foundation for hope. With that in mind, Arnow suggests his faith in the “fundamental goodness of human beings as bearers of the divine image” serves as the foundation of his hope or desired goal that the world will reflect his belief in the goodness of humanity. In his view, hope is not just faith/belief but is evidenced by actions based on that faith such that hope “finds expression in my efforts to build that world despite all the obstacles and setbacks along the way” (p. xiv).

This view of hope rooted in faith evidenced by human action is the central theme of the book. While Arnow reflects on biblical texts (the Christian Old Testament), he also draws heavily on Jewish history and tradition, including contemporary ideas and concepts. As we move along with this discussion of hope he reminds us that it’s important to distinguish between false and real hopes. That’s because hope matters. Thus, he writes: “even without the science to prove it, Jews know in their kishkas that if their ancestors had responded to their circumstances with despair instead of hope, the Jewish people would have vanished from the earth long ago” (p. xvi). As for God, God is the reservoir of hope. As such, God “is not static but rather dynamic, changing, evolving. Like God, in whose image we are created, we are not defined by the past or the present. I take this to mean that together with God, we inhabit an open future, the place where hope resides” (p. xvii).

Arnow’s Choosing Hope could easily function as a reference book, especially for preachers, who wish to draw upon Jewish wisdom in teaching about hope, but it is also readable and thus worthy of spending time simply reading it cover to cover. Whether one uses it as a reference book or not, Choosing Hope focuses on nine core Jewish teachings. The first teaching is Teshuvah or repentance. It serves as the gateway to hope because it involves self-examination. This core teaching invites us to engage in prayer and seasonal rituals that enable such reflection. With Teshuvah serving as the gateway or starting point of hope, we can then move to the second core teaching, that of Tikkun Olam or repairing the world.

I found his discussion of this term, which is widely used well beyond Judaism to be very helpful. In his discussion of this term, he draws on Ecclesiastes and Rabbinic discussions. While Ecclesiastes offers a rather cynical view of the possibility of repairing the world, the Rabbis coined this term to counter that pessimism. The belief here is that what is crooked can be made straight and it’s our job to make that happen. We can discover that this is possible by starting with a small piece of the world and fixing it. This chapter should prove very helpful to anyone wishing to understand what this term means with Judaism and how it translates outside of Judaism.

The third core teaching that expresses this vision of hope is found in the story of Abraham and Sarah and the role they play in Jewish self-understanding. Their faithfulness provides models of living in hope. From Abraham and Sarah, we move in chapter 4 to a discussion of the Exodus. He writes of the Exodus and its remembrance in the Passover, serving as a “beacon of hope for Jews wherever and whenever they have lived” … “and will live” (p. 61) As such the Exodus has become “Judaism’s master story of hope, coloring practically every aspect of Judaism” (p. 81). This discussion of Judaism’s master story turns to the concept of covenant. He explores this idea of covenant, which is central to Jewish self-understanding, in the context of Jewish morning prayer and Jewish sufferings in history, ancient and modern. This includes a discussion of the post-holocaust reality.

Here the question raised is one of theodicy—why do the innocent suffer? In that regard, he invites us to engage with the question: “what kind of covenantal relationship allows one partner to sit in silence while the other is annihilated? (pp. 96-97). These realities have put the covenant to a test that modern Jews struggle with. In this context, he writes that “we cannot hope that God will act to send redemption to the shattered world—but we can hope that God will strengthen our will to redeem it” (p. 102). This sense of covenant will challenge many who may not like the idea that fulfillment of this hope rests on our actions. Again, for Christians, this can be enlightening since many of our traditions make use of covenant language.

The next core teaching speaks of “hope for vindication” in the context of a discussion of the Book of Job. While it is usually understood to be a rather pessimistic book, it offers some two dozen references to hope. Job suggests that hope is not a piece of armor that offers unfailing protection against despair, but rather “hope is a thin thread that can tear or escape our grip, but there is no weaving, or living, without it.” In fact, despair and hope may live with us simultaneously (p. 126). But, it inspires the search for vindication. The conversation about vindication is followed by a discussion of Jewish eschatology in chapter seven. This is another chapter that should prove helpful to Christian reflection as Arnow explores eschatological concepts including the resurrection, messianic hopes, and Jewish understandings of the afterlife.

It is good to remember that Jewish understandings of eschatology are not monolithic. Any conversation about Jewish understandings of hope will take into consideration the role of Israel in the Jewish vision of a homeland. In this chapter (chapter 8) he speaks to the development of Zionism and its implementation. Since this is such a challenging topic in Christian-Jewish and Jewish-Muslim conversations, this discussion will prove very helpful. The hope of finding a homeland has been a central component of Jewish life for millennia, and for Jews, the assumption is that fulfilling this hope depends on the Jewish people themselves. What the future holds is unknown, but as Arnow writes, “trying to build a better future is not” a waste of time. Change is possible, and thus this hope must be acted upon.

The final core teaching focuses on the role humor plays in Jewish life. It shouldn’t be surprising, Arnow acknowledges, that comedians are often Jewish. It is humor that has enabled Jews to survive throughout difficult times. Arnow writes that “humor does more than make us laugh. It keeps us going, keeps us human” (p. 211). We might not expect to find a discussion of humor in a book like this, but it is central to Jewish understandings of hope.

As Arnow draws to a close, he reminds us that hope requires something of us. It involves work on our part. It is also rooted in, according to Arnow in Choosing Hope a belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity. That doesn’t mean Arnow believes that nothing evil or bad exists within the human family, only that there is the possibility inherent in our existence as humans to pursue that which is good. It is, he believes rooted in our creation in God’s image. That is something we can build upon. Therefore, hope is not mere optimism. It requires human action, though God serves as the reservoir of hope. While I might want to temper this foundation with a bit of Niebuhrian realism, I appreciate Arnow’s reflections on hope and our ability to choose to hope (through actions).

With that in mind, he offers two principles when it comes to a Jewish theology of hope. First, “Human beings are created in the divine image.” With that comes the second principle: “God has put the responsibility for fulfilling our hopes in our hands” (p. 212). This may sound like works righteousness to many Christians, but if we listen closely to our Jewish cousins, we might discover that committing ourselves to repairing the world by doing what is right does not earn us God’s love but is a reflection of our being created in God’s image. As Arnow makes very clear in Choosing Hope, Jewish theology affirms the goodness of humanity despite the many trials and tribulations Jews have faced throughout history. There is wisdom here that is worth exploring. Thus, as a Christian, I receive this wisdom with gratitude.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest books: Called to Bless: Finding Hope by Reclaiming Our Spiritual Roots (Cascade Books, 2021) and Unfettered Spirit: Spiritual Gifts for the New Great Awakening, 2nd Edition, (Energion Publications, 2021). His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.