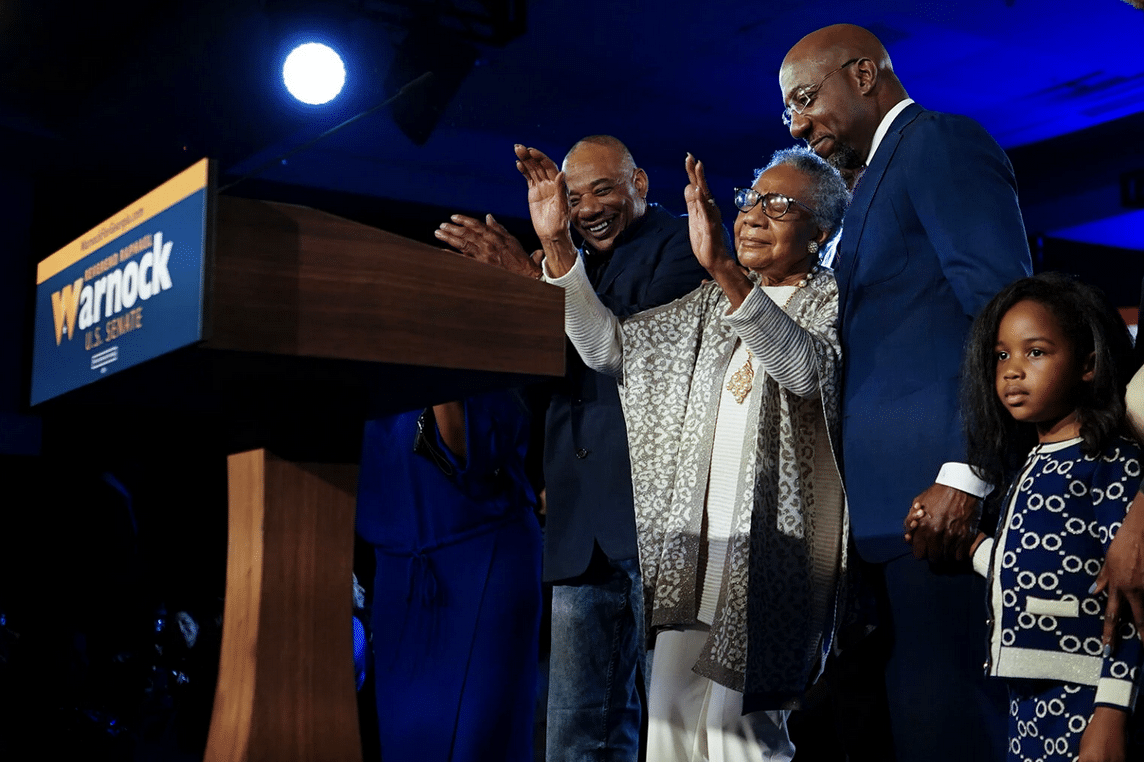

Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock speaks as he stands with his mother, Verlene Warnock, and his daughter, Chloe, during an election night watch party, Tuesday, Dec. 6, 2022, in Atlanta. Sen. Warnock defeated Republican challenger Herschel Walker in a runoff election in Georgia. (AP Photo/John Bazemore)

WASHINGTON (RNS) — When Sen. Raphael Warnock walked to the podium in Atlanta on Tuesday night (Dec. 6) to celebrate his election to a full term as a U.S. Senator, it was mere moments before he brought up a subject close to his heart and key to his win: God.

“Thank you from the bottom of my heart, and to God be the glory,” he declared to thousands of supporters, “for the great things God has done.”

The crowd erupted in jubilation and kept cheering as Warnock, senior pastor at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, a historic Black congregation once led by Martin Luther King, Jr., referred to “that American covenant: E Pluribus Unum” and described voting as a “certain kind of prayer.”

They were lines Warnock has used for years, sometimes from the pulpit, other times from political podiums, often both.

But his rhetoric seemed to hit differently that evening, bringing not only raucous applause from the crowd but also praise from liberal media observers. As Warnock finished his speech, MSNBC hosts Joy Reid and Rachel Maddow lauded his soaring oratory, with Maddow merrily suggesting that perhaps Democrats should elect more Baptist ministers — or at least ones who speak like Warnock.

The quip may surprise some, as liberal Democrats are commonly cast as “godless” by their conservative opponents. Warnock not only rebuts that kind of talk, he represents a particular brand of social justice-focused Christianity that favors voting rights and prioritizes the poor. By couching those issues in his faith, he offers a prominent counter to the religious right and appeals to the Democrats’ historic base among Black Protestants.

Warnock is someone who “embodies the best vision of progressive faith in America,” said Joshua DuBois, who oversaw faith outreach for Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign and in his administration. Dubois noted that Warnock — whose “pro-choice pastor” identity resonates with many liberals, be they religious or otherwise — has also been active in the Progressive National Baptist Convention as well as in ecumenical and interfaith circles.

“He’s someone who not only understands the perspective of progressives of faith and really lives in that space, but also will elevate that perspective in the halls of power,” said DuBois, who now runs the consulting firm Values Partnerships.

Now that Warnock, who has held onto his pulpit at Ebenezer, is freed from what seemed like a perpetual campaign for his seat, he stands to serve as both a champion for the resurgent religious left and as a model for Democrats seeking to expand their influence in the South.

Many on the left are watching to see what Warnock does now that he has a full term in the Senate. Just a few years ago, Warnock was walking through the halls of Congress in handcuffs, arrested for protesting Republicans’ proposed Medicaid cut with a group of Black clergy.

“I have a feeling that in a few days I’m going to meet those Capitol Hill police officers again, and this time they will not be taking me to central booking — they can help me find my new office,” he said just before winning his last runoff, in 2021.

In 2014, he was one of dozens detained at the Georgia State Capitol as part of a “Moral Mondays” demonstration urging local legislators to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Both protests involved or were connected to the Rev. William Barber II, the North Carolina pastor who started the Moral Monday movement with demonstrations in his home state and later co-founded the Poor People’s Campaign, restarting the effort organized by King shortly before he was assassinated.

Warnock and Barber regularly operate in each other’s orbits. The North Carolinian has preached at Warnock’s church, while Warnock appeared at one of Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign protests last August. They share several core concerns as well, primarily voting rights bills, such as the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and the For the People Act, which were the subject of Warnock’s first speech on the Senate floor.

But as Warnock has become a political insider, the nature of the duo’s relationship has changed. At a Poor People’s Campaign protest last year on Capitol Hill, Warnock arrived and appeared prepared to address the gathering, but Barber barred him from the microphone, citing the group’s policy of prohibiting politicians from speaking at their demonstrations. It’s a divide Barber has seen work in the other direction as well: President Joe Biden made a point to laud the Poor People’s Campaign while running for president but has evoked frustration from Barber since the 2020 election for, among other reasons, remaining silent on requests to host a White House meeting with anti-poverty advocates.

Even so, Barber and other faith-rooted advocates have Warnock’s ear. Barber told RNS he spoke with Warnock in November, shortly before the Georgia runoff. He pressed the senator to, should he win reelection, urge Democratic leadership to hold votes on voting rights bills before the next Congress is sworn in, as well as votes to protect abortion rights and raise the federal minimum wage.

“Because of his election, we have seen that the South can now be broken through,” Barber said, “but there needs to be an action that goes along with the election.”

The Senate is unlikely to pass any of the bills, even with a Democratic majority, but Barber noted Republicans will control the House of Representatives in the new year, making this month the best option for Democrats in the near-term.

“When God gives you a gift, use it,” he said.

Warnock, in keeping with a long history of Southern Black pastors’ activism on the vote, talks about voting as “sacred” and has echoed a common spiritual rationale for voting rights as a recognition that each human is made in the image of God. He mentioned voter suppression in his victory speech this week, noting many Georgians stood in long lines to cast their ballot.

“Just because they endured the rain and the cold and all kinds of tricks in order to vote doesn’t mean that voter suppression does not exist,” he said.

Adrienne Jones, an assistant professor of political science at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Warnock’s alma mater, said that a comprehensive voting rights agenda pushed by Black pastors and other advocates could result in pragmatic gains for Democrats in the South. New voting laws in Georgia and elsewhere have been widely decried by Democrats as suppressing voting by people of color, she noted, and neither the trend toward greater restrictions nor the uproar they spark is likely to abate as Southern states become increasingly competitive.

“If you want to have a democratic system where voting is an option,” Jones said, noting that Republican-led laws have made voting harder for many, “then you’ve got to prioritize the voting system and have it not be fettered by systems that result in biased outcomes.”

Black Protestants make up the lion’s share of Democratic voters in Southern states, and Obama and particularly Joe Biden owe their presidential nominations to Black religious voters in the Palmetto State, who helped keep Obama’s 2008 primary campaign afloat and rescued Biden from a string of defeats. Both men mustered sizable faith outreach efforts in South Carolina, now on track, at Biden’s urging, to replace Iowa as the first state to vote in the Democratic presidential primaries.

In general elections, Southern states often reject Democrats, even those that lean into faith. When Jamie Harrison ran against Senator Lindsay Graham in South Carolina in 2020, he often spoke at churches and foregrounded religion in his advertisements. It wasn’t nearly enough: Harrison lost by 10 points.

But when Harrison took over as chairman of the Democratic National Committee last year, he remained bullish about the party’s prospects in the South — and the role of faith. “You go to where people are and engage them in things that are of value to them,” he told RNS at the time. “Religion and faith is a huge component of that, particularly in the Sunbelt across the South.”

In a statement to RNS this week celebrating Warnock’s victory, Harrison argued that the Democratic Party’s values are in line with his personal faith, “whether it’s in our support for opportunity and justice or our fight for equality.”

Fronting one’s faith may risk alienating some Democratic voters, as Warnock seemed to acknowledge in his victory speech, assuring those who are “not into … religious language” that “our tent is big.” But Warnock has so far succeeded in politics by being the pastor he is, depending on the overlap in values between the religious left and the broader Democratic Party and the deep faith of his most ardent followers.

“The times are dark, but the light, the Scripture says, shines in the darkness — and the darkness overcometh it not,” he said in his victory speech.

Behind him, some raised their hands and pumped their fists in response. Others shouted from the crowd: “That’s right!”