We all know we are dangerously polarized by political party. But there is a growing sense that we are also polarized by faith. “Unaffiliated” is considered by many to be progressive or “woke” and “Christian” is seen as conservative or more drastically, a right-wing challenge to democracy.

No matter what you think of that description politically, something deeper is lost here: that Abrahamic tenets themselves are among the foundations of liberal democracy. Given that, the political left may need to step back and recognize the importance of theological ideas to democracy, and the right may need to look at the kind of democratic policies that faith seeks.

The Founding Fathers, in developing their new experiment in democracy, drew from Aristotelian republicanism, natural law theory, and British liberalism, but Abrahamic principles were also key to the mix. To be sure, other philosophies and faiths may support liberal democracy. But in nations descended from Abrahamic traditions like the U.S., religion is not somehow conservative and anti-democratic while secularism is progressive and pro-democracy. Abrahamic principles are at the core of democracy.

It’s not a division — it is embeddedness.

One Abrahamic principle is the imago, the idea that we’re made in God’s image. This grounds liberal democracy in asserting that all persons, precisely because they are created in God’s image, have inalienable worth and dignity. Therefore, they have inalienable protections and freedoms which may not be violated: the freedom from torture, arbitrary incarceration, etc.; the freedoms of conscience, speech, and assembly; and the rights to due process and public/political voice.

One complaint against the religious genealogy for these freedoms and rights is that we can value and protect human dignity humanistically, without God-talk. So religious tenets are not needed. But what secures the mandate to value and protect? Why should I worry about others at all? The ease with which self-interest and fear trounce the image of God in others suggests that we need a very firm anchor indeed. Could be that if more people took the image-of-God idea seriously, we’d have less abuse and violence? Just saying…

A second complaint is that the imago is anthropocentric and leads to disregard for the rest of the planet — and thus, for instance, to environmental degradation. But if, to avoid anthropocentrism, we say people are no different from whatever animals or vegetables you ate for lunch, there is no reason to afford us liberal, democratic rights.

A second theological ground for liberal democracy is the relational nature of the universe. The Abrahamic faiths recognize that there could be nothing at all, no existence. But there is something, an entire universe. The reason for the existence of anything is what some call God. Every existing thing partakes of this transcendent Being in order to exist at all. The metaphor in Genesis is that God breathes of his breath/spirit into Adam. So there is a foundational relation between each existing thing and the transcendent God.

Now, God is radically different from every earthly thing. God surpasses time, space, and materiality while we have material bodies and live through time. Yet we are in relation with this radically different Being in order to exist. So the structure of the world, the very way it’s set up, is that very different things — God and world — are in foundational relation. The first law of nature, so to speak, is difference-in-relation.

Because difference-in-relation is the way everything in the world is, human beings too are different from each other yet also in foundational relation. We become who we uniquely are through our relationships. Consider how infants develop: through networks of relations and interactions. These may be with those nearby but also through our worldwide connectedness as the factors that affect health, safety, nutrition, educational and job opportunities, etc. may not be close at hand.

Like the imago, difference-in-relation underpins the worth that liberal democracy grants to each (different) person. It also underpins the idea that each of us, in foundational relation to others, must be concerned about their dignity, protections, and freedoms. Liberal democracy is not “freedom and protections for me and abuse for you.” It is a system of values, institutions, and laws aimed at shielding freedom and protections for all.

A third antecedent of liberal democracy is the covenantal nature of humanity. Covenant is a reciprocal relationship for the flourishing of the other. Each (different) person is in covenantal relationship with God and with other persons. Unlike contract, which protects interests, covenant protects relationship — the community, the polity, and the system of values and law in which the freedoms and protections given to me are given to all.

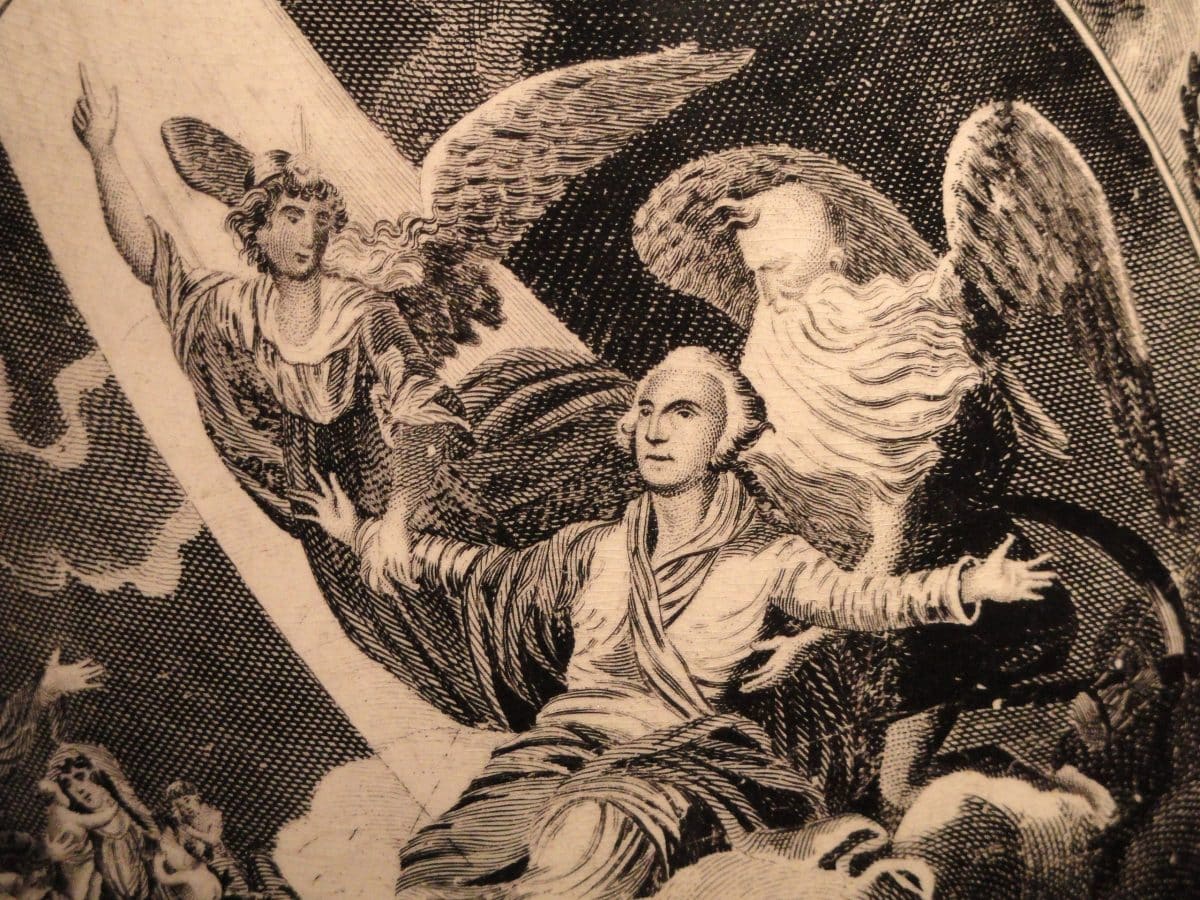

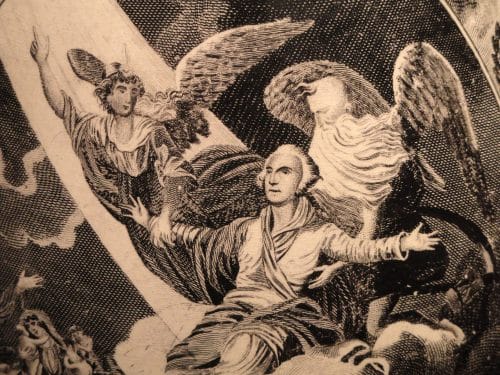

Apotheosis of George Washington, Herculaneum Pottery, c. 1800-1805, John James Barralet, artist. Exhibited in the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

Fourth is the biblical notion of human moral agency. In a relational universe where covenant is a reciprocal bond, every person is responsible for maintaining it. Sustaining the freedoms and protections for all is our task, not the responsibility of only kings or priests. The First Testament, for instance, provides explanations for its commandments. Why? Why not say they must be blindly obeyed? It’s because, as Yale Professor Christine Hayes notes, the Bible addresses readers as persons “capable of moral reasoning” (p. 139). The renowned sociologist of religion Robert Bellah provides a useful summary: covenant is “a charter for a new kind of people, a people under God, not under a king… a people ruled by divine law, not the arbitrary rule of the state, and of a people composed of responsible individuals” (Kindle Locations 4700–4701, 4864, emphasis mine).

Liberal democracy draws from this idea of human agency and responsibility. For without the notion that ordinary people have the capacity to make moral choices for the community and common good, there is no reason to grant us ordinary folk self-rule. Might as well leave it to some monarch or dictator.

The importance of these principles to liberal democracy is not a call for a state church, Christian Nationalism, or any other religious nationalism. First, these principles are central to many faith groups and theologies. No one could legitimately claim a monopoly on them to claim state-church status. Moreover, the best implementation of these premises may be clear to God, but we mortals have only imperfect interpretations. And these interpretations differ. But different interpretations are refined in relation in democratic discussion and debate. That’s the point.

It is not only a premise of the secular Enlightenment and “marketplace of ideas” that ideas must be debated. It is a premise of our theological tenets themselves: difference-in-relation and the moral agency of (different) persons who, in covenantal commitment to each other, work those differences out.

The late Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, Lord Jonathan Sacks, put it this way: “truth emerges from the quite different process of letting our world be enlarged by the presence of others who think, act, and interpret reality in ways radically different from our own” (p. 23).

The importance of Abrahamic principles is no guarantee that people will always keep to them. We are relational, covenantal, in God’s image, and yet we have the capacity to lose sight of all this — the prophetic outcry of many Abrahamic scared texts. Yet unmoored from these foundational precepts — from the value of all people and our covenantal mandate to a system that protects it — liberal democracy is adrift and vulnerable. The question now, riffing on Ben Franklin, is whether we can keep it.

This entails avoiding an unhistorical, purely “secular” past that erases the theological grounds of liberal democracy. If you want honest, democratic debate, you can’t begin by finessing your past. And it entails implementing policies, as moral covenant keepers, that enable all to live with the freedom, dignity, opportunities, and protections of persons in the image of God.

Marcia Pally teaches at New York University and held the Mercator Professorship in the Theology Faculty of Humboldt University (Berlin), where she is now an annual guest professor. Her most recent books are White Evangelicals and Right-wing Populism: How Did We Get Here?; From This Broken Hill I Sing to You: God, Sex, and Politics in the Work of Leonard Cohen; and Commonwealth and Covenant: Economics, Politics, and Theologies of Relationality. Commonwealth and Covenant was selected by the United Nations Committee on Education for Justice for worldwide distribution. Prof. Pally has been a contributor to U.S. and European periodicals, including Religion News Service, Religion and Ethics, Commonweal, The New York Times, and The Guardian.