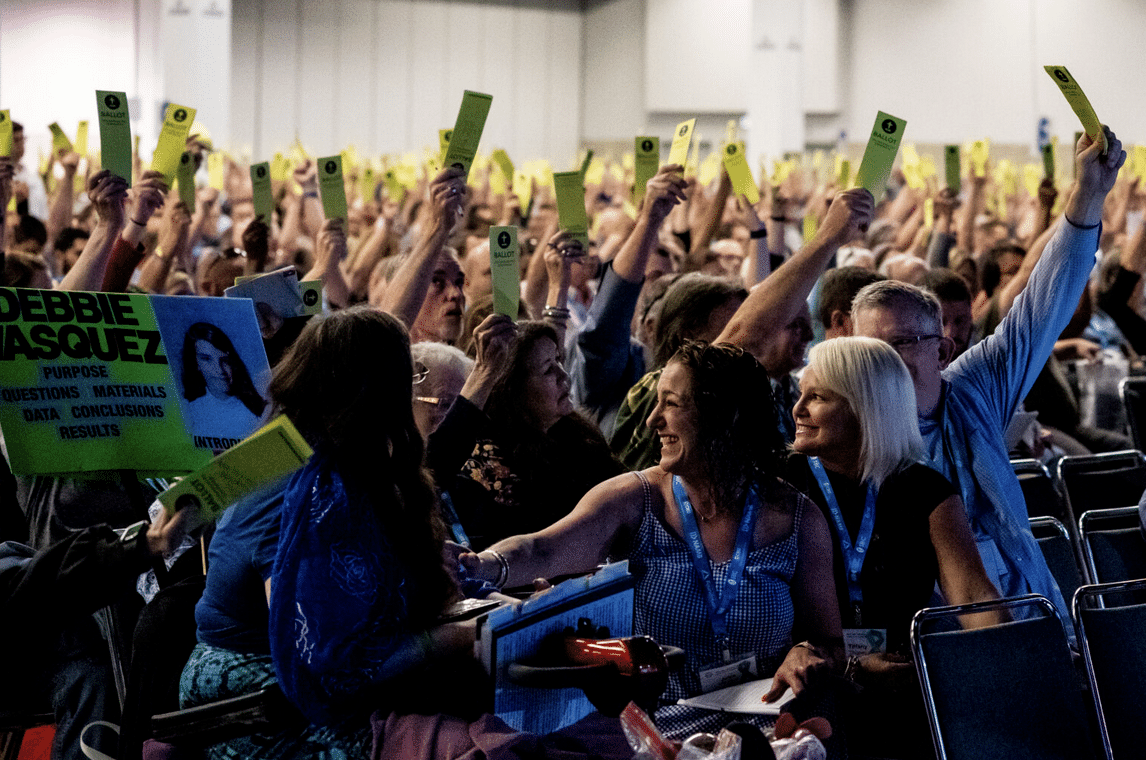

Abuse survivors Debbie Vasquez, from left, Jules Woodson and Tiffany Thigpen turn to watch as messengers vote on a resolution in favor of sexual abuse victims during the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting, held at the Anaheim Convention Center in Anaheim, California, on June 15, 2022. RNS photo by Justin L. Stewart

(RNS) — For years, Southern Baptist Convention leaders refused to listen to abuse survivors, ignoring their concerns and labeling them as enemies of the nation’s largest Protestant denomination.

After the release last spring of a major report detailing decades of mistreatment of survivors, Southern Baptist leaders pledged to change.

One of their first steps: setting up a confidential hotline where allegations of abuse could be reported to trauma-informed experts.

The hotline was meant as an interim measure until long-term responses were put in place. But until recently, very little was known about how it operated. That led one survivor and longtime abuse advocate to ask some pointed and uncomfortable questions about the hotline in an online publication.

“I had questions about the process,” Christa Brown told Religion News Service in an interview.

In particular, Brown said she was concerned about the role Rachael Denhollander, another survivor, had with the hotline. A prominent advocate and lawyer, Denhollander has publicly criticized SBC leaders over their treatment of survivors and her activism helped prompt the Guidepost investigation. She has also helped advise abuse survivors and consulted with Christian groups, including the SBC, on how to better care for survivors.

Brown argues that Denhollander’s roles as both a survivor advocate and a consultant for the SBC could lead to a conflict of interest. Brown worried survivors who call the hotline might be referred to Denhollander without knowing that she also works with church leaders.

Brown’s Baptist News column led Guidepost Solutions, which oversees the hotline, and the SBC task force working on abuse reforms to release statements about how it works.

But it also prompted a public conflict among abuse survivors and advocates, which played out on social media. Some backed Brown. Others saw her column as an attack on Denhollander.

The conflict also revealed a deeper challenge for Southern Baptist leaders trying to address abuse in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination. Because SBC leaders mistreated survivors for years, no one trusts them. Every attempt they make at reform is viewed with skepticism, most of it justified.

Brown worries readers missed the bigger point of her column.

“My purpose is not in any way to degrade Denhollander, an individual for whom I hold great admiration and gratitude for all she has done in broadly raising awareness about the dynamics of sexual abuse,” she wrote.

Instead, Brown wanted to draw attention to the lack of transparency about the hotline.

According to the response put out by Guidepost, a small number of trauma-informed staffers respond to callers. Any information collected by those staffers is kept confidential. Guidepost does not investigate any allegations. Instead, they are referred to the SBC’s Credentials Committee.

Guidepost said that on two occasions, out of “hundreds,” people reporting allegations have asked to be connected to an advocate.

The SBC task force also said all reports are kept confidential. No task force member or adviser, including Denhollander, was given information about callers to the hotline.

South Carolina pastor Marshall Blalock, who chairs the task force charged with implementing abuse reforms approved last summer, said survivors and advocates have every right to ask questions in this process.

“When concerns are raised, it is important to hear them,” he said.

Blalock said the task force is working as quickly as it can to implement reforms and wants to be transparent about the process. He acknowledged that earning trust will be a long-term process.

“We don’t want to do any more harm,” he said.

Survivor and advocate Jules Woodson said she agrees with Brown that there should have been more transparency about how the hotline operates. Without accurate information or details from the task force about the hotline, some survivors feared the worst, she said, or made assumptions based on incomplete information.

She also said survivors don’t all agree on how to respond to the SBC’s reforms. Some believe the SBC can never be reformed. Others see a “sliver of hope,” she said.

Woodson puts herself in the latter camp.

“For years, survivors have been pleading for the SBC to listen, and we were dismissed and ignored,” she said. “Now people want to listen. I do think the door is open for survivors to have a voice.”

For that reason, she supports Denhollander’s involvement with the task force. Woodson also said Denhollander, who declined to comment, has long assisted other survivors and is a trusted advocate and leader. She also understands other survivors might disagree.

Woodson said the process of implementing reforms will be complicated.

“There’s going to be tension,” she said. “That’s a sign of progress.”

The concerns over the abuse hotline reveal the larger challenge facing the SBC in dealing with sexual abuse. Because of the past actions of church leaders and congregations, neither survivors nor the general public has much trust in them.

Church leaders in the SBC and other denominations also likely still have not grappled with how much harm was done to survivors, said psychologist Diane Langberg, who has spent 50 years working with survivors of abuse and trauma.

“They want to say that they get it,” she said. “But it’s too soon. People do not understand, not only the damage done but the depth of the damage.”

Even after 50 years of working with survivors, Langberg said she is still learning about the harm done by abuse in the church. She believes churches and Christian leaders have yet to acknowledge the depth of their failure to care for and protect abuse survivors, which she said has led to lifelong harm.

“We have utterly failed God,” she said. “We protected our own institutions and status more than his name or his people. What we have taught people is that the institution is what God loves, not the sheep.”

The first step in regaining trust is not to ask for it, said Langberg. Church leaders, she said, will need to spend years listening to survivors and walking alongside them.

And things will never go back to the way they were before, she said.

Churches are supposed to be refuges, said Langberg, that demonstrate the character of God, which has led people to trust churches. But when abuse happens, that trust is shattered.

“The idea that something can be mended to the point where it is as if (abuse) didn’t happen is not a true idea.”

Brown remains skeptical because of her long-term history with the SBC. For years, she was labeled as a troublemaker. Southern Baptist leaders dismissed her concerns out of hand, with one criticizing her for using “hyperbole, argumentative language, strident tones, or pejorative adjectives” in dealing with SBC leaders and cutting off all official contact with her in a now-infamous 2006 letter.

Southern Baptist leaders disowned that letter last year. But Brown, who was mentioned repeatedly in the Guidepost report, said the SBC’s Executive Committee has done little to make amends to her.

“They are the ones who did wrong,” she said. “They are the ones who should make it right.”