(RNS) — Against a patriotic backdrop of U.S. and Florida state flags, Governor Ron DeSantis took the stage at a private Christian university in West Palm Beach, Florida, last Wednesday (Feb. 15) to unveil a new “Digital Bill of Rights.” The governor, known for cracking down on diversity, equity and inclusion programs and AP African American studies courses, also blasted Big Tech for surveillance and censorship.

That same day, an English professor at the university was intercepted outside his classroom by school administrators who cited concerns that he was “indoctrinating students,” according to the professor. Samuel Joeckel, who has taught at the university for over 20 years, reports that they informed him his contract renewal letter was being delayed until leadership could review his lessons on racial justice.

At issue, according to Joeckel, is a three-day unit he teaches in his Composition II course for first-year students at Palm Beach Atlantic. A parent reportedly called the university’s president, Debra Schwinn, with concerns about the unit Joeckel says he’s been teaching without issue for 12 years.

“It’s time for universities like mine to have these kinds of difficult conversations,” Joeckel told Religion News Service. “And I worry that the university has succumbed to a political culture that will not allow those conversations to even get out of the gate.”

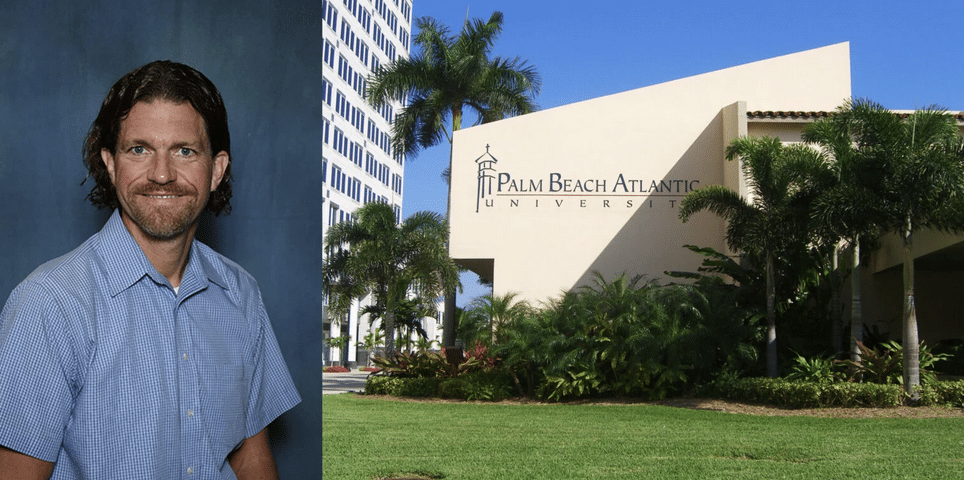

Professor Samuel Joeckel has worked for Palm Beach Atlantic University for more than 20 years. Headshot courtesy of PBAU website, photo by Nick Juhasz courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Palm Beach Atlantic’s provost contends that the situation is a dustup over pedagogy, not censorship of racial justice education, according to an internal email shared with RNS. “Faculty are free to choose a theme that unifies their Composition II course,” the email says. “However, it is important that the Composition II objectives remain the focus of the course.” A spokesperson for the university declined to comment for this story, saying, “The university is not commenting on personnel matters.”

Joekel, PBA students and alumni and some academics see the incident as part of a broader suppression of racial justice education in the state of Florida and in conservative Christian colleges across the U.S.

Joeckel told Religion News Service he incorporates a racial justice unit into his writing class “precisely because I teach at a Christian university.” The unit includes excerpts of Christian historian Jemar Tisby’s “Color of Compromise,” readings from Martin Luther King Jr. and relevant polling data, according to the professor. Joeckel said he wants students to come to their own conclusions while completing essays on the topic.

“It’s my attempt to do something that the university says it takes very seriously, the integration of faith and learning,” said Joeckel. “It’s the work of the gospel, as I understand the gospel. If a unit like mine can’t be taught here, we’re in bad shape.”

In the last week, students and alumni have drafted a public petition to save Joeckel’s job, with over 1,400 signatures and an open letter to the university’s president asking her to publicly apologize and commit to academic freedom.

Danielle Hawk, a PBA alumna and former democratic nominee for Congress, believes the university’s treatment of Joeckel is directly linked to the political climate in Florida.

“I think it fits into this broader culture, especially what we’re seeing in the state of Florida right now with Ron DeSantis and his censorship, white-washing issues of race, and really, a frankly paranoid surveillance of academic institutions. And he’s doing that in private schools and public schools,” observed Hawk.

Warren Throckmorton, a professor of psychology at Grove City College in Western Pennsylvania, says viewing racial justice education as a threat isn’t just a Florida problem.

A year ago, Grove City made headlines when a group of parents published a petition accusing the Christian school of promoting critical race theory, an academic and legal theory that examines how systemic racism has shaped law and society. The school quickly became engulfed in a politicized dispute resulting in a board report that acknowledged instances of “CRT advocacy” while absolving the school from allegations of “going woke.”

“What the administration was doing to help raise awareness about social justice and racial consciousness … all of a sudden was considered subversive. Some people were being interrogated and became worried about what they were teaching,” said Throckmorton.

This year, things on campus have simmered. Throckmorton said there’s “cautious optimism” that last year’s debate won’t stifle what’s taught in the classroom. But the debate is still stirring online, where stakeholders concerned about CRT encroachment have authored another petition lamenting the direction of the college and calling for the president’s departure.

According to Throckmorton, “The people who have been opposing the current president and the college have argued that colleges like Hillsdale, who reject what they call ‘wokeness,’ are thriving. And colleges that are like Wheaton or Calvin, that are not like Hillsdale … that are taking racial justice seriously, aren’t doing as well.”

Hillsdale College, a Christian college in Hillsdale, Michigan, known for its conservative political identity, saw an enrollment surge of 16% in fall 2021 and reported an endowment topping $900 million that same year. The school advertises on Fox News, and in 2020 Donald Trump appointed the school’s president to chair a committee created to help curb “anti-American” scholarship.

According to Hillsdale’s website, the college rejects “the dehumanizing, discriminatory trend of so-called ‘social justice’ and ‘multicultural diversity,’ which judges individuals not as individuals, but as members of a group and which pits one group against other competing groups in divisive power struggles.”

Other politically conservative Christian colleges have also found success in terms of numbers. Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia, whose then-President Jerry Falwell Jr. championed Donald Trump’s White House run in 2016, boasted its highest enrollment in both online and residential programs in fall 2022. Trump also held a campaign rally at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where enrollment nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020, thanks in part to new online degree offerings.

“In a general sense, at conservative colleges, I’ve seen them become more explicitly partisan,” Matthew Warner, a critical cultural scholar who previously taught at Hillsdale and Liberty, told Religion News Service. He said that political identity is increasingly reflected in their student bodies.

“I think that as institutions have become more politically vocal and more partisan in how they market themselves — when Hillsdale College started advertising with Rush Limbaugh, for example — what you end up getting is a larger portion of the student body that’s coming for specific reasons … year on year on year, more of the freshman class was already politically aligned with the public reputation of the college.”

Leadership at other Christian colleges could be following suit. In October 2021, faculty at Cornerstone University in Grand Rapids, Michigan, voted no confidence in their new president, Gerson Moreno-Riaño, the day before his inauguration, citing a culture of “fear and suspicion” and his alleged opposition to diversity, equity and inclusion efforts.

Moreno-Riaño, who previously served in executive leadership at Regent University, wrote an article in 2020 calling today’s college classrooms “myopically fixated on the perspectives of the oppressed.”

Hawk believes Palm Beach Atlantic’s leadership is also on the path to partisanship. Before she graduated in 2017, she told RNS, it was “obvious” that it “leaned conservative,” but it “wasn’t necessarily a hostile environment” to non-conservatives. That changed, she said, in 2020 when the university honored Melania Trump as that year’s “Woman of Distinction.”

Conservative politics isn’t the only thing uniting these schools. Several, including Liberty, Grove City and Palm Beach Atlantic, don’t offer tenure (except at Liberty’s law school, where it’s required for accreditation). And Regent, Liberty and Cornerstone have all seen layoffs that allegedly targeted faculty and staff who didn’t align with leadership’s politically driven mission.

Many Christian colleges are trying to be defined by their faith, not politics, and to offer an education rooted in theology and open to people of all political viewpoints. But in today’s political climate, argues Andrea Turpin, a Christian historian of religion in American higher education and professor at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, simply having a “political spread” can get an institution accused of losing its identity.

“That’s what I see happening here at Palm Beach, that’s what happened at Grove City,” said Turpin. “There were individual people or classes that were exploring the connection of the faith with issues that have gotten coded as politically left in the contemporary American context.”

When donors, parents and other stakeholders apply labels like “CRT” indiscriminately, even broad lectures on racial justice are flagged as indoctrination. This is especially the case in Christian higher education, argues psychologist and educator Christina Edmondson, where there’s a risk of “this conversation being funneled through this cheat-sheet of labeling things quickly as either right or wrong, biblical or unbiblical.”

Edmondson acknowledged that many Christian colleges are financially dependent on churches and other outside funders to keep the lights on. But, she said, it’s in the vulnerable times that Christian colleges discover what they really stand for.

“That’s when you can demonstrate what I believe to be the best of the institutions, this Christian courageous tradition of not being controlled by dollars, but seeing oneself as standing for justice and righteousness, come what may,” she said.