Lately, I have been thinking deeply about the concept of home for those of us across the African diaspora. I am a native of Demopolis, Alabama, a small town in the Black Belt of Alabama, 49 miles west of Selma. As far back as I can trace my matrilineal ancestry, I am a descendant of those who were abducted from our homeland and enslaved in Demopolis in the early 1800s. It is the only home we know. There are relatives who are old enough to remember the stories from Grandma Johanna, born in 1860 in Demopolis, who believed that our family came from West Africa. As a child, I dreamed of “going home” and being welcomed by my African kin.

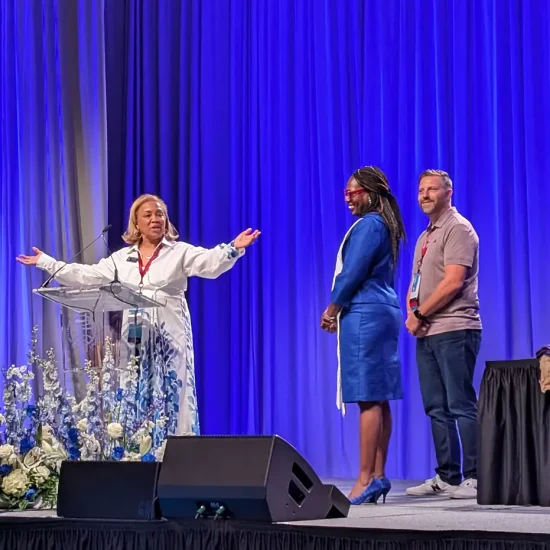

Rev. Dr. Cassandra Gould

I recently traveled with our executive director, Rev. Alvin Herring, and our International Board Chair, Mr. Ron White, to Ghana. It was my fifth trip there. As usual, I was comforted at the sight of the red clay dirt, immediately visible from the plane when landing in Ghana. It is the spitting image of the dirt in Demopolis. In addition to meeting with and learning from faith leaders in our partner org, Faith in Ghana Alliance (FIGA), at the invitation of Father Stephen Amoah-Gyasi, a leader with FIGA, we visited his home village near Cape Coast. The hospitality extended during our visit was indescribable. Every trip I have made to Ghana has been marked by the familiarity of the kind of radical hospitality often associated with Black southern families.

We also received a surprise invitation to meet the village chief and the elders. With tears in his eyes, the chief addressed us in his native language, Twi. Father Stephen translated the words, “I am so grateful that the Creator allowed me to live long enough to see our children return home. The colonizers snatched you away from us; welcome you back home.” The one word I understood is the common refrain from Ghanaians when they encounter African Americans, “Akwaaba,” which means welcome in Twi. As three Black Americans, those words deeply impacted us. Not only had hospitality survived the Middle Passage, but kinship and connection were still intact, even against the backdrop of the violent history of enslavement and colonization. We were officially home.

Earlier this month, Rev. Al Sharpton spoke powerfully to the experience of being Black and understanding the concept of home. As he eulogized Tyree Nichols, an unarmed 39-year-old Black man who was brutally beaten and killed by Memphis police officers, he proclaimed, “All he wanted to do was get home. Home is not just a place. It is not just a physical location. Home is where you are at peace. Home is where you are not vulnerable.” He repeated, “All Tyre wanted to do was get home.” I sat and cried for this family like I have done for a long list of Black families who lost children and other family members to violent injustice.

Rev. Sharpton’s poignant illustration pierced my heart. Sadly, Tyre now joins a cast of those who became ancestors prematurely, when all they were trying to do was get home. I can’t help but think of these recent ancestors: Sandra Bland trying to get to her new home in Houston, Michael Brown Jr., trying to get home in Ferguson, Breonna Taylor, who thought she was at home in Louisville, George Floyd in Minneapolis, Mother Ruth Whitfield and nine Black shoppers trying to get home from the grocery store in Buffalo, and an innumerable list of innocent Black people in America who deserved to get home safely and now never will.

Black Star Square, also known as Independence Square, in Accra, Ghana (Ifeoluwa A. / Unsplash)

Part of my role at Faith in Action is working with our international team to build relationships, engage with, and learn from Ghanaian faith leaders across faith traditions who are working together to build beloved community and to ensure everyone has a safe place to call home. This work is holy and purposeful to me and connects me to the home that my ancestors were snatched away from centuries ago. Our work, domestically and globally, is rooted in justice, equity, and belonging.

Globally we are working on modeling multifaith, multiracial, gender-equitable solidarity rooted in faith. Our siblings in Ghana model this well, specifically Muslims, Catholics, and Protestants who work together daily to change the lives of the most vulnerable in Ghana. Despite women not being ordained in some of those traditions, their leadership is centered and supported. The FIGA, for instance, is led by Hajia Ayishetu Abdul-Kadiri, a brilliant Muslim woman who leads with strategic wisdom.

While divisions exist everywhere, the multi-faith interconnectedness and commitment to working together for justice and equity I continue to witness among our Ghanaian siblings is a model we can and must adopt here in the United States, if we believe justice is worth pursuing. This work of ensuring that everyone has a place to call home, and safe passage to and from home – not just making space for people, but ensuring they belong – is the aspiration for multifaith solidarity work in America.

Rev. Dr. Cassandra Gould lives in Washington, D.C. She serves as the Senior Strategist at Faith in Action and is ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.