“Is history the new theology?”

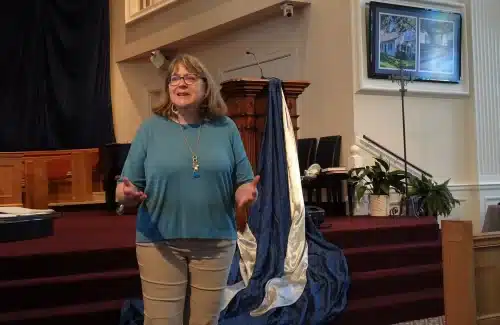

Diana Butler Bass posed that question on Saturday (June 17) to start a lecture at First Baptist Church in Columbia, Missouri. And she made the case for the affirmative.

The author of numerous books on American religious history and a Substack newsletter The Cottage, Bass spoke as part of the congregation’s year-long 200th anniversary celebration. But in addition to lifting up the usual stories of God at work, the church is also wrestling with parts of its history long left unspoken. Like the fact that many of its founders and preachers were enslavers. So the church welcomed Bass to help them think about history in fresh ways.

“I’m very excited that you’re telling some new stories here and that you’re trying to figure out what your story is,” she told the congregation. “History can be changed if we know to tell the right stories, and sometimes we even stumble into the right stories unawares.”

An issue facing congregations, organizations, and individuals as they engage in justice work, Bass said, is to consider “what memory has been lost and can it be recovered?” Finding the untold, forgotten, or even censored stories remains critical.

Diana Butler Bass speaks at First Baptist Church in Columbia, Missouri, on June 17, 2023. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

In her sermon during Sunday worship the next day, Bass talked about hospitality from the story of Abraham and Sarah welcoming the strangers in Genesis 18 and Jesus sending out his disciples with instructions in Matthew 9. After retelling a story from her latest book, Freeing Jesus, she noted that the book includes that “hidden story inside of its most obvious story.” The idea of a story within a story led her to the climax of her message about the two biblical passages.

“It’s the hidden story inside of the obvious story that is often the most important story,” she said. “It is the most important story that Abraham and Sarah would not have had their son without Abraham first offering water to the three strangers. It is the hidden story that Jesus says, no, bypass those who refuse to offer you hospitality for the kingdom of God can only be received by those who are willing to welcome the stranger.”

That idea of finding the important hidden stories was the key point of her lecture on Saturday about history. And during her talk, she demonstrated how to do exactly that, with profound insights that need to be heard beyond that sanctuary in the Show-Me State. So this issue of A Public Witness provides a seat to listen to Bass’s lecture as she considers the stories we tell about history, especially about race and religion.

Empty Spaces

Bass noted that many scholars are paying attention to “what arguments we’re having in the public square about history right now.” She gave examples from Florida and other states of efforts to limit what professors can teach about history. Such conflicts show the importance of history today — a level of public conflict she didn’t expect when she started her graduate studies in the history of American Christianity.

“Years ago, when I was a seminary, I loved both history, church history and I really liked theology. But one of the things I noticed is that theologians always got in trouble. And I don’t really like conflicts. Kind of conflict-avoidant, actually. And so I thought I’ll become a historian. And that way I can just sort of stand on the side of the fray and say, well, you know, back in the 18th century people used to xyz,” she said.

But today, Bass added, people aren’t fighting about theology but history.

“Now we have all these historians who are always in trouble all the time, especially on social media and people whose jobs are actually being threatened,” she said.

“People had big public fights over things like infant baptism and double predestination. Now, we could walk down the streets here in Columbia and maybe find ourselves a hardcore neo-Calvinist sort of type and manage to get into a fight about double predestination, but I can pretty well guarantee you that if we go into a coffee shop or a bar — oops, Baptists — anywhere around here, you’re going to be hard pressed to find anybody who even knows what double predestination is, much less who John Calvin is,” Bass added. “People just don’t really argue about this same stuff anymore. But instead, we’re arguing about history. So while people might not know who John Calvin is, they know who this guy is: Robert E. Lee.”

On her slides projected in the sanctuary, Bass then moved from showing a picture of Lee to a picture of the massive monument to him that long stood on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. She highlighted the difference between the history of information like that in a Wikipedia entry about Lee to the history of interpretation seen in that monument. Thus, she noted that people where she now lives in Virginia “had a particular interpretation of those facts, and Monument Avenue was their physical representation of that interpretation.”

Since history is both information and interpretation, she explained, it matters how we tell stories about history. She demonstrated that evolution with additional photos from Monument Avenue of people protesting the Lee statue, then an empty pedestal after the removal of the Lee statue in 2021, and then a patch of grass after the pedestal’s dismantling last year.

The statue of Robert E. Lee is removed from its pedestal on Sept. 8, 2021, in Richmond, Virginia. (Amr Alfiky/National Geographic via AP)

“This is what we’re fighting about. This is a fight about history. And it’s not a fight about facts of history,” Bass said. “The facts aren’t in dispute. But what’s in dispute is how we interpret that. And how as community we put physical reminders around those interpretations, which allow us to find meaning and purpose for our own lives today. And that’s what interpreting history is always about. History is always about the people who inherit the stories, people who inherit the facts finding a sense of themselves and their own vision for the future in those facts, and how we choose to write the narrative about those facts.”

With the removal of the Lee monument and other statues honoring Confederate leaders, Bass pointed out that “now what we have in Richmond is a whole bunch of empty space.” Which leads to questions about what to do with those spaces and how to tell these historical stories today.

“I’d like to suggest that it isn’t just Richmond, that in effect all of America right now is Richmond, Virginia,” she said. “The fight has been going on about meaning and identity of American history. And in many places, the space is now empty. What’s going to go up in its place? We don’t really know yet.”

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

A Whole Story

After highlighting the empty spaces in Richmond, Bass told a personal story about learning that some of her Quaker ancestors in Maryland in the 17th and 18th centuries had enslaved human beings. She also noted that one of them left the Quaker church amid a dispute, perhaps over slavery, and joined the Anglican church where slavery wasn’t condemned. Bass, who is Episcopalian, admitted, “I hate this part of the story more than anything else.”

She connected her attempts to discover this part of her family history to First Baptist’s own efforts to tell forgotten parts of its historic ties to slavery.

“That’s what your history page made me think about. It made me think about the big contemporary argument we’re having in Richmond, Virginia. It made me think about oh my goodness gracious these nice Baptists in Columbia wrestling with the fact that half of their founders or thereabouts held human property,” she said. “We’re wrestling with an interpretation of what it means to be a child of God, of what this history of being Christian is supposed to be about. And we have been wrestling with it from the very beginning.”

But just like the “original sin” of slavery can be found in the founding of First Baptist and in her own family, Bass noted that “there were prophets protesting that sin from the beginning.” In fact, in the same Quaker congregation in Maryland her ancestors had been part of, William Southeby wrote a powerful pamphlet against slavery in 1696, right around the time her ancestors left.

“This is not something that Black Lives Matter invented in the summer after George Floyd was killed,” Bass argued. “So anybody who gets up and says that you can’t teach this stuff because it’s not American history, it’s some radical woke thing that a bunch of socialists just made up in the last couple of years, they don’t know anything about American history. This is the part of American history that has been buried because we were trying to protect our ancestors from the shame of that sin. But we had ancestors who knew and who didn’t want to go along for the game plan.”

So she said that how she deals with having ancestors who went along with slavery is by telling the story, not to make her ancestors look bad but so we can do better today. Rather than memorializing blind spots of those in the past, she urged finding ways of telling new stories about the past in a quest of “moving ahead fearlessly into a better future.”

“When you find out … they did bad things in the past, instead of celebrating it by burying the parts that you think made them look less than saintly or less than heroic, what you do is you tell the whole story. You tell the whole story and its complexity and its beauty and its pain and the problems that people created on the other end of it,” Bass said. “It’s about reframing the narratives so that the stories tell a deeper truth that gives us a sense of meaning and purpose in our own time.”

Left: Diana Butler Bass speaks at First Baptist Church in Columbia, Missouri, on June 17, 2023. Right: Diana Butler Bass and Brian Kaylor. (Word&Way)

So Bass commended First Baptist for telling its story during its 200th anniversary year in a new way by highlighting the slavery of many of its founders and searching for the names of those who were enslaved.

“To have churches do this kind of work I think is astonishingly a great place to start because hopefully the churches can do it in ways that create community, that begin to model a kind of a spiritual element to the doing of history,” she said. “We can do new stuff with history. We can put up new monuments.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor