Dietrich Bonhoeffer, reflecting on the state of the Protestant Church, questioned whether it was possible to establish a church grounded “solely in Scripture and confession.” If the answer was no, Bonhoeffer concluded, “Then there is only return to Rome or under the state church of the protest of Protestantism against false authorities.”

Rodney Kennedy

The Southern Baptists now are something new — the first Radical Reformation church whose entire existence hinges on Roman Catholic doctrine. The Southern Baptists are engaged in a long slow return to Rome in a couple of very particular ways: one pagan and one religious.

Lutherans and Episcopalians are of course more Catholic in liturgy and government. The Southern Baptists are still allergic to Catholic liturgy, bishops, and creeds, but in other ways they are now thoroughly Roman.

There are two meanings I intend by describing Southern Baptists as Roman Baptists. Southern Baptists are “Roman” in the pagan sense, in the first-century sense of the Roman model of the family, of male patriarchy. Then, Southern Baptists are “Roman” in the sense of following the Catholic insistence on no women in the priesthood, opposition to gays, abortion, and a development of what amounts to a Baptist Magisterium — led by Cardinal Al Mohler. What Mohler considers a biblical mandate against women in ministry I consider a first-century Roman family model. Mohler claims he is being Christian, but the model he supports is pagan.

First, the “Roman” family is the Southern Baptist model of family. George Lakoff labels this the “strict father family.” A comparison of the first-century Roman family model with Lakoff’s “strict father” trope is instructive.

“The strict father is the moral leader of the family and is to be obeyed. The strict father protects the family from the pervasive evil in the world — and mommy can’t do it. The strict father trope has been plastered onto the American political life in Donald Trump — he presents himself as the strict father who is strong and tough enough to destroy the enemies of the family. This is why conservatives are obsessed with authority, obedience, discipline, and punishment In this world there must be an absolute right and wrong. The categories must be absolute, the lines clearly drawn. This is the defining purpose of biblical literalism.

We are dealing here with what Aristotle identified as “essences.” If your identity is defined with respect to a strict-father family, where male-over-female authority rules, then the legitimacy of gay marriage can threaten your identity. If your enemy is evil, then you have no choice but to use the devil’s own means against them. This is where Trump enters the equation. He does the devil’s work for the evangelicals as a protective father. The same model is used by Putin and Erdogan.

Ancient Rome was a man’s world. In politics, society, and the family, men held both the power and the purse strings. Families were dominated by men. At the head of Roman family life was the oldest living male, called the “paterfamilias,” or “father of the family.” He looked after the family’s business affairs and property and could perform religious rites on their behalf. The paterfamilias had absolute rule over his household and children. If they angered him, he had the legal right to disown his children, sell them into slavery, or even kill them.

Roman women usually married in their early teenage years, while men waited until they were in their mid-twenties. As a result, the materfamilias was usually much younger than her husband. As was common in Roman society, while men had the formal power, women exerted influence behind the scenes. It was accepted that the materfamilias was in charge of managing the household. In the upper classes, she was also expected to assist her husband’s career by behaving with modesty, grace, and dignity.

St. Paul, a Roman citizen, does not take the time to develop a Christian family model. He simply maps his Christian theology onto the Roman strict father metaphor as his own. In the midst of hammering out church polity, evangelizing the Roman Empire, and trying to avoid being killed, Paul didn’t have the time to give attention to a radically different conception of family, marriage, and ministry for women.

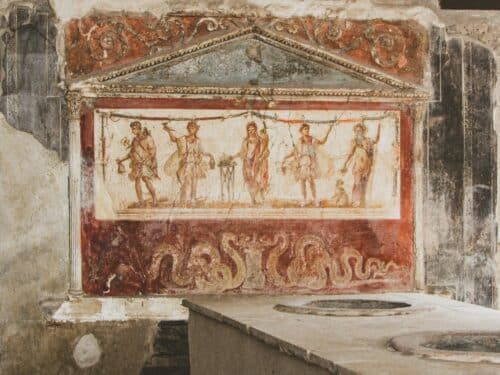

An ancient Roman fresco in Pompeii. Casey Lovegrove / Unsplash

There is no theology of the family in Paul’s writings. He left the system as he found it. This can be seen in his attitude toward slavery. He told Christian slaves to be good slaves and asked Philemon to take back Onesimus, his slave: “Perhaps this is the reason he was separated from you for a while, so that you might have him back for ever, no longer as a slave but as more than a slave, a beloved brother — especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.”

When Paul does give instructions related to family life, marriage, and women, his words have the feel of advice or opinion that fails to attain the depth and profundity of Paul’s justification theology. Paul’s instructions in Ephesians are right out of first-century Roman understandings: “Wives be subject to your husbands. Children, obey your parents. Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling.” While Paul attaches Christian understandings of love and speaks of Jesus, he is leaving the “Roman” structure in place. And the Southern Baptist model has not changed much from this Roman conception.

The second sense in which Southern Baptists are “Roman” relates to the refusal to admit women to ministry. This is as Roman Catholic as possible. The reasons for opposing the Southern Baptist strictures on women in ministry are well documented and to the rest of the Christian world that is not Catholic or Missouri Synod Lutheran, obvious. I would only add comments by Roman Catholic New Testament scholar Dominic Crossan because he offers an enlightened look at the role of women in ministry in the first-century church.

Crossan notes that in Mark 6:7 “the twelve,” and in Luke 10:1 the “seventy others,” are sent out “in pairs.” Why? There are two other texts that may clarify what is happening. One is a highly symbolic story in which two followers of Jesus travel from Jerusalem to Emmaus on Easter Sunday. One of them is identified as Cleopas, a male; the other is left unidentified. I presume, in such a combination of named and unnamed pairs, especially in Mediterranean society, that the second person is a woman. She is not, however, specified as Cleopas’s wife.

Another text is 1 Corinthians 9:5, in a context where Paul is discussing his own missionary activities: “Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a believing wife [adelphn gynaika], as do the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas?” That translation makes the problem a simple one of support for both the missionary and his wife, as long as she, too, is a Christian. The literal Greek “sister wife” is translated into English as “believing wife.” But is Paul talking about real, married, Christian wives, and, if so, how exactly are we to imagine what happened to their children in such situations? And, more specifically, how could the unmarried Paul be accompanied by his wife? Crossan concludes, “My proposal is that a ‘sister wife’ means exactly what it says: a female missionary who travels with a male missionary as if, for the world at large, she is his wife.

Southern Baptists make arguments from history, the Bible, and theology. I am convinced that these arguments are unbiblical, unchristian, and not in tune with Christian history. David Buttrick warns of swallowing such ideas whole: “Or, perhaps, God draws us into faith through a masculine church; before you know it we’re protecting the pronouns and two-legged tailored vestments: ‘Everything we got’s wrapped up in you,’ sung by a bass-voiced choir.’”

And so, it will not suffice to say that Southern Baptists are Protestants like all the others in our nation. They must be called by their rightful honorific — America’s first Roman Baptists.

Rodney Kennedy has his M.Div. from New Orleans Theological Seminary and his Ph.D. in Rhetoric from Louisiana State University. The pastor of 7 Southern Baptist churches over the course of 20 years, he pastored the First Baptist Church of Dayton, Ohio – which is an American Baptist Church – for 13 years. He is currently professor of homiletics at Palmer Theological Seminary, and interim pastor of Emmanuel Friedens Federated Church, Schenectady, New York. His seventh book – Good and Evil in the Garden of Democracy – is now out from Wipf and Stock (Cascades).