(RNS) — The Rev. Susan Sparks, a minister and a professional comedian, uses humor in her sermons to help her American Baptist congregation in New York City consider ways to approach those with whom they disagree.

Pastor Joel Rainey, who leads a West Virginia evangelical church, hosts a “special edition” of his preaching podcast to answer questions he’s received from his politically diverse congregation about hot-button issues.

Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin recently preached about anger, realizing it was an emotion felt by congregants of her Reform synagogue in Washington, no matter their stance on the Israel-Hamas war.

Fueled by their work in comedy, psychology, and theology, some clergy say reducing polarization is both a spiritual necessity for them and an ever-increasing part of their job description.

Sparks, who has been on the Laugh in Peace comedy tour with a rabbi and a Muslim comic, said she can see shoulders relax and smiles appear on faces when she starts a sermon in a joking matter — such as the battle over what topping is appropriate on a sweet potato casserole. But then she can move into tougher subjects as she addresses her multiethnic congregation.

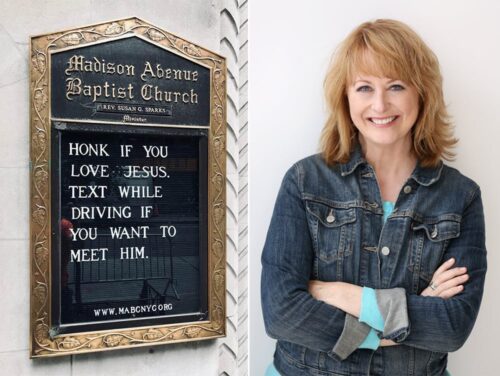

The Rev. Susan Sparks regularly uses comedy both in the preaching and signage at Madison Avenue Baptist Church in New York City. (Courtesy photos)

“I did a piece on how cancer does not discriminate between Republicans and Democrats,” said Sparks, a cancer survivor, referencing another sermon. “There’s things that we all experience, and we can start there and find that place, enjoy a little moment where we can share something and take tiny baby steps off that to move into harder territory.”

Preaching is one means, she and others say, that clergy can attempt to help congregants get along better with each other and, by extension, their families and friends.

“We used to have congregations where people would be shaped by Scripture and by their faith leader and then they would listen to the news and say, well, that does or doesn’t fit in with my faith,” said Andrew Hanauer, president and CEO of One America Movement, a Maryland-based organization founded in 2017 that supports leaders of congregations, from Southern Baptists to mainline Protestants to Muslims.

Now, as people often align first with a viewpoint they’ve heard on cable news or read in social media, he said clergy have to answer new questions: “How do you preach in a way that moves people out of complacency about the world in general but also lets them know this is not a Democratic church or a Republican church, it’s a church for all God’s people?”

In recent years — especially since 2020 — as clashes over race, politics, and health have escalated into what Hanauer calls “toxic polarization,” clergy can feel like they are walking a knife’s edge in their sermons, as they preach to divided — and sometimes hostile — congregations.

One America Movement, along with the Colossian Forum and other clergy resource groups, has found that pastors are seeking ideas for how to preach in ways that heal, rather than further widen, the social and political divides within their congregations.

In the last year and a half, Hanauer’s organization has worked with more than 100 clergy as they consider sermons or other messaging related to polarization.

Hanauer, a lay member of a nondenominational evangelical church, said his organization offers training to congregations or their leaders on how to manage difficult conversations as well as listening sessions with clergy who are suffering from burnout and exhaustion. Its work has ranged from training rabbinical students — who went on to preach sermons against polarization — to a multi-faith initiative to address the opioid crisis in West Virginia.

“It’s not about going from red to blue to purple,” he said. “It’s about going above the partisan divisions and having a compelling vision for the world that is more hopeful and more positive.”

Schmelkin, a former staffer at One America Movement, has used what she learned from the organization’s listening sessions and trainings to find nuanced ways to address polarization in her sermons as an associate rabbi at Washington Hebrew Congregation.

She chose to preach on anger on the first Friday night in December, knowing the congregants, representing diverse views, likely were all feeling some level of rage amid the Israel-Hamas war.

Schmelkin talked to them about how God is described in the Torah as “slow to anger,” or “erech apayim.” She recommended drawing “a deep, intentional breath before reacting” as “the first step we can take to better manage our anger, to be a little more like God.”

In an interview, Schmelkin said she has had one-on-one discussions with people in her community who are grappling with divisions over the war, from parents whose college-age children hold different views from theirs to Jewish millennials who have discovered via Facebook that some of their close friends do not share their perspectives on the conflict.

In November, she led a “healthy conversations” workshop for young adults coping with those differences and provided a script they could use that had been developed by the One America Movement and Over Zero, a group that uses communication to reduce division and violence. One participant told Schmelkin afterward that she used the script with a friend with whom she had major disagreements about the war, “and she felt like it saved her friendship.”

Rainey said he has learned terminology like “metaperception” — how people believe others perceive them — from One America Movement, which he first connected with when he joined other faith leaders in responding to the opioid crisis. He brought the concept into the pulpit by encouraging congregants to have “one conversation” with an individual instead of talking to others about that person.

“You don’t have to wonder what they think about you — you’re going to know,” said the pastor of Covenant Church, a predominantly white congregation in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, where about 600 attend Sunday services. “Having one conversation is my way of saying don’t ever say anything about somebody that you wouldn’t say directly to them.”

Rainey, who has been involved in interfaith activities, including a musical concert with Jews and Muslims at his church, said he has used his special-edition podcasts to address issues like Christian nationalism and Israel, issues on which his congregants have conflicting opinions.

“When Psalm 122 says ‘Pray for the peace of Jerusalem,’ it’s not just the Jews,” he told listeners. “It’s everybody living in that space.”

Attendees participate in small group discussions during the second annual One America Movement Summit in May 2023 in Atlanta. (Courtesy photo)

The Colossian Forum, a Michigan-based organization founded in 2011, originally held issue-specific workshops on topics such as human sexuality and politics but since 2022 has broadened its focus through two-day “WayFinder” trainings. More than 600 leaders from Christian organizations have gone through the training, seeking help with divisions over anything from “leadership changes to sanctuary carpet color,” according to the group’s website.

During the in-person training, the Rev. Jess Shults and other staffers encourage participants to develop “a vision for conflict transformation,” she said. Using spiritual and leadership practices, they try to help participants see that divisions are not always a negative — they can be an opportunity to “reflect Christ in the midst of conflict.”

Shults said preaching alone is not sufficient to address polarization in a congregation.

“In an ideal setup, one would be pairing a sermon with, then, some kind of post-sermon conversation during an adult-ed hour,” said the former Reformed Church in America pastor, “so that one is recognizing the place of power they have when delivering a sermon and the community could be brought in.”

Shults also suggests clergy bounce their ideas off other church leaders as they prepare their sermons, to ensure the message reflects “the voice of the Spirit” and Scripture rather than their burnout or exhaustion.

The Rev. Raymond Kemp, who teaches theology at Georgetown University and preaches regularly at a Catholic church in Potomac, Maryland, said a lengthy tenure in a pulpit can earn you the trust to address hot-button issues like race or immigration. Ordained in 1967, he has been preaching for over 30 years at Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Church.

“You can’t rent a preacher and have somebody come in and talk about polarization, I don’t think, without creating polarization,” he said. “They got to know the preacher and they got to know that the preacher enjoys his craft or her craft and has built up enough trust in a community.”

Matthew D. Kim and Paul A. Hoffman argue in their book “Preaching to a Divided Nation” that it is imperative for clergy to address polarization and seek unity, not just for the sake of the congregation but as a peaceful example for the world beyond it.

“It’s not good enough for members of the family of God to make it through a worship service without engaging in physical or verbal warfare with a neighbor in the pew,” they write in the 2022 book. “There is a greater purpose for the church.”

Though it is hard to measure the level of impact preachers might be having on polarization within their congregations, many remain interested in getting tips and training for their sermons.

The Colossian Forum, whose name is based on the verse in the New Testament book of Colossians that says “all things hold together in Christ,” reports an average increase of 20% in a leader’s confidence in helping a community dealing with conflict after taking its WayFinder training.

It also has seen an increase in calls from churches, seminaries, and other Christian nonprofits as the 2024 election season approaches.

“We barely survived 2020, and nobody wants to repeat that,” Shults said their leaders have said, “and so we need to be doing work now to help us be equipped to live into the next presidential election differently.”

This story was supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.