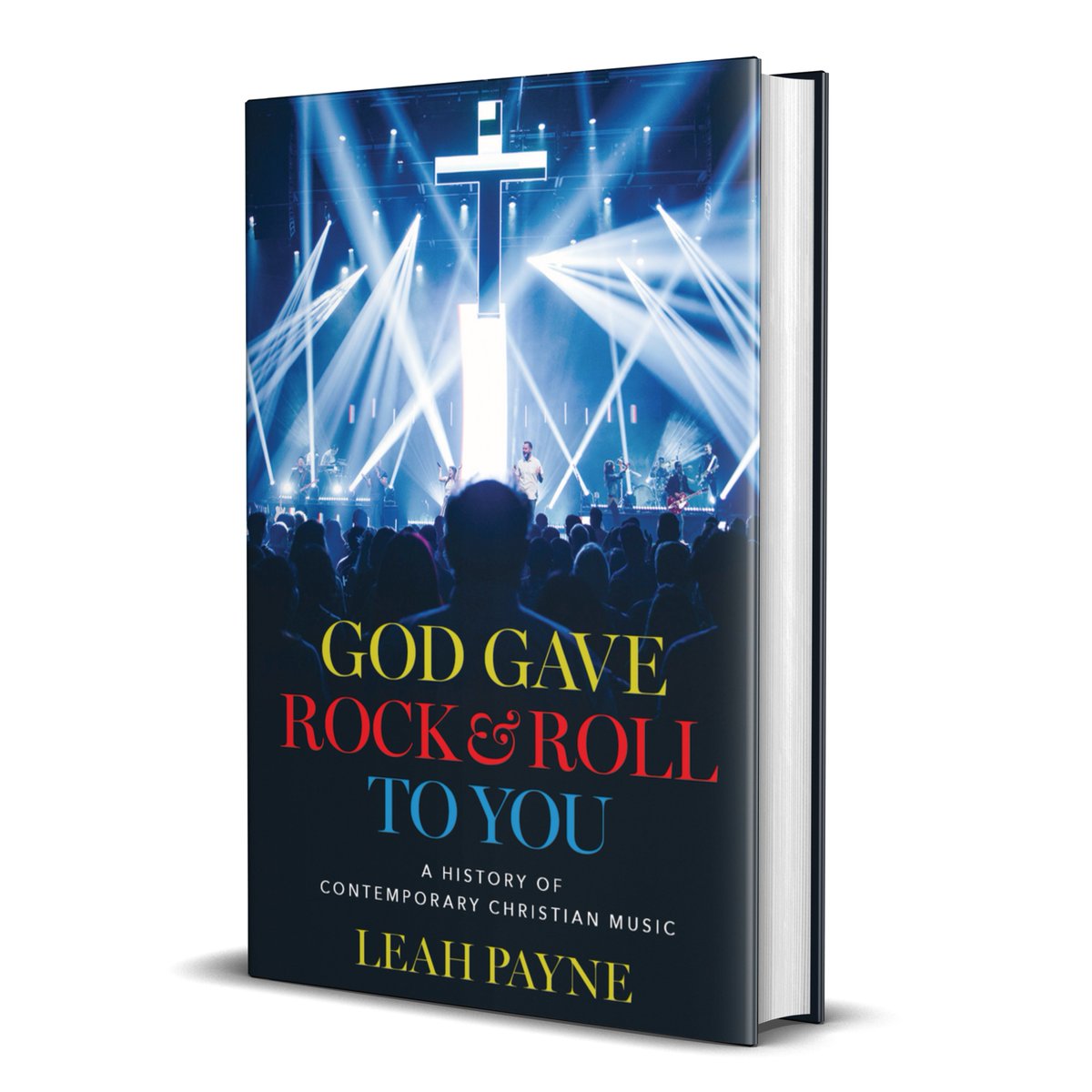

GOD GAVE ROCK AND ROLL TO YOU: A History of Contemporary Christian Music. By Leah Payne. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2024. 256 pages.

Note on the review: normally I review books provided to me by the publisher. The publisher provided me with a PDF but found it difficult to work with. Therefore, this review is based on a Kindle eBook that I purchased. Therefore, page numbers are for the Kindle edition.

Back in the 1970s, when Christian rock music was just emerging on the scene, Larry Norman, who was known for the pushing boundaries of evangelical Christianity asked a question on the minds of many young evangelicals who were attracted to the popular music but were not sure if it was acceptable to listen to it. So, Norman sang an anthem many of us embraced: “Why should the Devil have all the good music?” So, a new music industry was born, with Norman being at the forefront.

Robert D. Cornwall

On a personal note, I was first introduced to what became known as Contemporary Christian Music back in the mid-1970s. At the time we just called it Jesus Music. This Jesus Music allowed us to enjoy the sounds of rock music while listening to more “edifying” lyrics. Thus, this music served as a key component of our Christian life. I encountered this music while living in the southern Oregon city of Klamath Falls. It’s not a big city, but we regularly enjoyed visits from some of the biggest names in Christian music. We got to hear live and in concert Love Song and Barry McGuire, who toured with the Second Chapter of Acts. These acts appeared at a local auditorium, while other groups and musicians appeared at our church. That included a recently converted singer named Keith Green. If necessary, we traveled across the mountain to Medford where we caught Andre Crouch concerts, which were always powerful. We also heard the Talbot Brothers and Mustard Seed Faith (one of my favorites). Then During my college years, my friends and I drove up to Portland to catch Larry Norman and Andre Crouch concerts. I was so committed that at one point I gave away much of my secular music, including my beloved Moody Blues albums. When I moved to Southern California in the early 1980s to attend seminary, I worked at a Christian bookstore, which was a key distributor of Christian music. I also obtained free tickets so Cheryl and I could attend Amy Grant and Imperials concerts. We also got tickets to the Christian music festival held at Knott’s Berry Farm. Since my bookstore was in Glendale, California, some of the Christian musicians came into the store, including Leslie Phillips. In other words, at one time I was deeply immersed in what has come to be known as Contemporary Christian Music (CCM for short). I was able to share much of my story with Leah Payne, the author of God Gave Rock and Roll to You (you will find my name listed in the acknowledgments). Leah is a historian of American Christianity who teaches at George Fox University in Oregon.

Talking with Leah about my own history with CCM took me back to an earlier day when I fully embraced this music. Reading her history of CCM, which goes back to a time before Jesus Music came on the scene, opened my eyes to a larger picture of this particular musical entity, which as we discover in reading her history is a lot more complex than just listening to rock music with Christian lyrics. It is the story of an industry that became so profitable that major labels bought in and Christian bookstores, the primary distributor of the music boomed. As she notes in her introduction, “CCM encompassed many genres and often sounded like mainstream music, but what made it distinctive is that it was created by and for, and sold almost exclusively to white evangelicals. Consumed by millions, CCM was the soundtrack of evangelical conversions, worship, adolescence, marriage, child-rearing, and activism” (Kindle, p. 1).

Payne begins her story of CCM in the late nineteenth century when the revivals of the day included music as part of the package. These revivals introduced new music, which found a home in churches and homes through the publication of songbooks. She takes the story up to the present, culminating with the events of January 6, 2021. What we encounter as we read through this thought-provoking history is a story that is rooted in nineteenth-century revivalist evangelicalism and its descendants, including Pentecostalism and the Charismatic Movement. We watch as the music industry develops, crests, and then begins to decline. We see how this music was rooted in white suburban evangelicalism and often aligned itself with conservative Republican politics. We learn that the primary purchasers of this contemporary Christian music were Christian mothers who wanted their children to have a safe form of music to listen to instead of the secular music that pounded the airwaves. Why not listen to Love Song rather than Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young? As we move through the story of this music, we learn much of the backstory, which will prove surprising and even unsettling to many readers, especially evangelical readers. The image that the industry projected was of Christian musicians who lived lives that were beyond reproach. However, that was not always true. Thus, we learn about sexual infidelity on the part of some leading singers and musicians, as well as drug use. While these Christian musicians were supposed to be straight some were gay and lesbian. In other words, some lived lives not much different from many of the secular musicians that they were seeking to replace in the hearts and minds of young white evangelical Christians.

My experience of CCM is largely limited to the 1970s and 1980s, though like many pastors I have drawn upon the worship music that began to emerge back in the 1970s when the Maranatha Praise albums began to emerge. This music was later supplemented by several other entities. By the 2000s, the primary expression of CCM was to be found in the so-called worship or praise bands. There are several reasons why this happened, which Leah details for us. Among the reasons for the transition from concert bands such as Stryper and Petra, or Christian singers/entertainers such as Sandy Patty, to worship bands, are the demise of the Christian bookstore together with the rise of streaming services, such that the gatekeepers for Christian music were replaced. By following the history of CCM, we see how it reflected trends in music, such that groups like Love Song, which had a country rock feel, gave way to disco and metal and later hip hop. In essence, CCM mimicked what was available in the larger cultural milieu. Again, there was a purpose here. Christian moms understood that their kids were attracted to certain kinds of music, so why not offer them a Christian alternative? Thus, the industry offered Stryper— “a Christian glam metal band known for yellow-and-black-striped spandex bodysuits, big hair, and guyliner” (p. 73).

Payne writes in her introduction that what she attempts in the book is to “trace how white evangelical caregivers in the United States came to see Christian spins on American popular music—even transgressive genres like death metal—as invaluable tools for molding their children socially, spiritually, and politically’ (p. 2). As such over time this music was used to “encourage teenage citizens to conform to conservative evangelical norms and strengthen the nation” (p. 2). There is a strong thread in the book that highlights the role that political allegiance plays in the story, such that one of the most influential Christian musicians, Michael W. Smith, a singer whose music is sung in many Mainline Protestant churches, is deeply aligned with conservative Republican politics.

Leah Payne writes God Gave Rock and Roll to You from the perspective of a historian of American Christianity. But she also writes from within the community she writes about. Like me, Leah has been influenced by this music. She is quite upfront about her own experiences, even as she seeks to tell the full story, warts and all. So, as a result, what she does is unveil how the music emerged, how it was understood, and how it was used. It might be at one level entertainment, but for many, it was much more than entertainment. It was designed in part to be evangelistic. It also carried political overtones. Those of us who experienced this music are reminded here that many of our favorite musicians and singers were deeply embedded in dispensational premillennialism. Leah shows how many of the songs and the “sermons” delivered by the singers emphasized the second coming of Jesus. Larry Norman sang “I Wish We’d All Been Ready” while Barry McGuire turned his Vietnam War protest song, “Eve of Destruction” into a word about the second coming. But these singers weren’t alone in their promotion of dispensationalism. Even Amy Grant was known to share the word about the imminent return of Jesus and the promise of the rapture. It might not always be in the songs. Sometimes it was found in the preaching they shared as they sang. I remember Larry Norman singing about the rapture, but perhaps conveniently I forgot about Amy Grant’s preaching!

While apocalyptic messages were ubiquitous, especially in the 1970s, as Hal Lindsey’s “Late Great Planet Earth” was all the rage, later on, another theme emerged. That was the message of “purity culture.” Several leading CCM artists, including Rebecca Saint James, proclaimed the purity message. Of course, not everyone was fully embedded in purity culture. Leslie Phillips not only left it behind, but she moved out from CCM. Not everyone lived the purity lifestyle, as we discover from the broken marriages and divorces of figures such as Amy Grant, as well as the infidelity of Sandi Patty. Then there is the coming out of major singers such as Ray Boltz, Jennifer Knapp, and Marsha Stevens (best known for her song “For Those Tears I Died”), who revealed that they were gay or lesbian, and paid the price for it. You can have an affair, take drugs, and be reclaimed. But you can’t be gay or lesbian and be part of the industry.

Then there is the political side of the equation as I mentioned earlier, with most of the leading CCM artists, especially Michael W. Smith, being deeply embedded in conservative politics. They made such themes as abortion, homosexuality, and sexual mores, along with defense spending, immigration, and more, part of the agenda. While there was a strong connection between CCM and Republican politics, not everyone embraced the message. There have been a few, such as John Fischer, one of the earliest Jesus Music producers, who expressed serious concerns about these political alliances.

In the pages of CCM Magazine, he warned that synergies of profit and politics in CCM were signs of danger. “When Christianity gets votes, it pays,” he argued. “When Christianity aligns itself with a growing socio-political power that is already moving the mountains of big government, it pays. When Christianity feeds the fire of a public and militaristic righteous indignation, it pays. When Christianity provides a scapegoat for personal guilt by attacking the moral ills of everybody else, it pays.” Fischer worried that the industry’s profitability would lead to unsavory alliances between Christians and their business and political partners. “When Christianity pays,” he wrote, “any opportunist can show up to collect. You can be sure they’re here” [p. 88].

When I read this, I decided to go back and listen to Fischer’s music, music I once listened to as a youth, on Spotify (remember it was streaming services like this that contributed to the downfall of Christian bookstores).

Then there’s the theology that gets expressed. There were the Pentecostals and Charismatics who embraced forms of dispensationalism and basic fundamentalist doctrines. But other singers were attracted to and supported by neo-Calvinists, such as John Piper. Many of them complained of the shallowness of the theology present in much of Christian music, which they saw as being too feminine. The Neo-Calvinists wanted to make sure that men and women knew their proper roles. Thus, some of the fixtures of this movement, such as Mark Driscoll, emphasized hyper-masculine Christian rock. But, while this movement emphasized masculinity, the majority of CCM singers and musicians already were male, despite the presence of some significant women singers/musicians. I found this information fascinating because it wasn’t part of my story. But it reminds us that music can be molded to fit any theological perspective.

As I read God Gave Rock and Roll to You, I found myself being nostalgic, even as I had my eyes opened to dimensions of this reality, especially the political dimensions of the industry, which covers multiples of genres. Leah is an excellent writer, historian, and cultural analyst. There is so much good information here that will at points prove nostalgic for some, while also revealing aspects of this music that many of us find problematic (at best). Thus, this is an enlightening and enjoyable read, even if many will find what she reveals here troubling. So, while enjoyed reminiscing, I also realized that what she reveals here is pertinent to understanding our current cultural/political moment. By underscoring the role CCM plays in connecting conservative evangelicalism with Trumpism, we realize that there is more to this than music. She also helps us understand the business side of Christian music, which shouldn’t surprise us. But it’s important to better understand how all of this functions, and the impact it has on the musicians, their families, churches, and Christian families. Fortunately, Leah Payne has given us God Gave Rock and Roll to You to serve as an important resource to help us better understand this phenomenon that continues to evolve (even if many evangelicals don’t like that word!).

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.