(RNS) — For most Native American children in the late 19th century and early 20th, education was neither a right nor a privilege. Indigenous children from Florida to Alaska were taken away, sometimes by force, to residential schools run by the government and often by denominations that operated under government contracts.

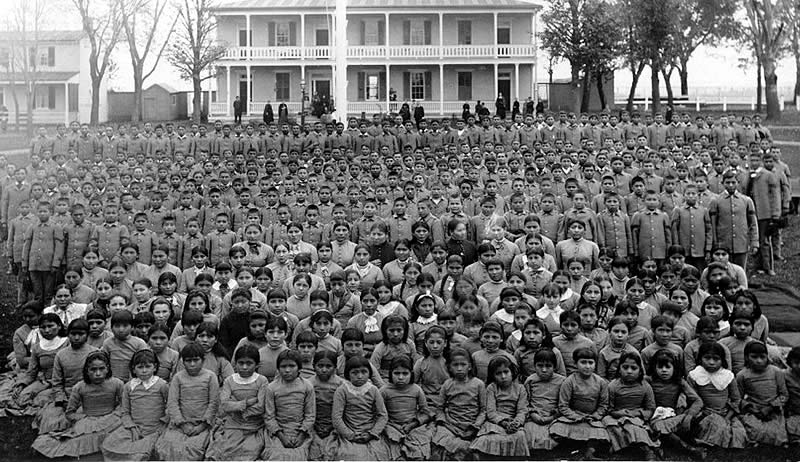

Pupils at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, circa 1900. (Photo courtesy of Creative Commons)

The aim of the education was to teach the children European American ways. Anything Indian, from language to clothing and dance, was forbidden. The system left a trail of trauma and death amid a quest for mass assimilation into white settler culture.

Now the Episcopal Church, which was involved in running at least 34 of the schools, has begun to reckon with the outsized role it played in this history. Last June, the church’s Executive Council allocated $2 million in a truth-seeking process aimed at documenting how Episcopal-run schools impacted lives for generations — and to explain why things happened as they did.

When Episcopalians gather next week (June 23-28) for their General Convention in Louisville, Kentucky, a panel event will bear witness to boarding school legacies still impacting families and tribal communities. Meanwhile, two Episcopal commissions overseeing the research are asking bishops churchwide to grant access to archives in their regions and to recruit research assistants of their own.

The U.S. government operated or supported 408 boarding schools between 1819 and 1969, according to a 2022 Department of the Interior report under the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. “The United States pursued a twin policy: Indian territorial dispossession and Indian assimilation, including through education,” the report says.

How the Episcopal Church used its considerable influence in crafting that federal policy must be understood before restorative justice can occur, said the Rev. Lauren Stanley, a research commission member and canon to the ordinary for the Episcopal Diocese of South Dakota.

“To simply say, ‘Yes, we participated in running schools’ without saying, ‘Because we helped formulate the policy’ denies truth, justice, and the possibility of conciliation which we hope will lead to reconciliation,” said Stanley in an email.

In Canada, where a similar boarding school system is blamed for eroding Indigenous languages and cultures, a truth and reconciliation process led to a $6 billion settlement with tribes in 2006 and multiple major settlements since then. Pope Francis, visiting Canada in 2022, apologized for the Catholic Church’s role in what he called “cultural destruction and forced assimilation.”

Members of two Episcopal commissions overseeing research on Native American boarding schools meet in Seattle, Oct. 27, 2023. (Photo courtesy of Pearl Chanar)

But in the United States, where church records haven’t been made public and often aren’t digitized or consolidated, Americans aren’t being taught what happened. Studies show only a handful of states include the story of Native American boarding schools in their history curriculum standards.

The research done already shows the Episcopal Church was no minor player in the boarding school system. The 34 known schools are far more than previously identified, but people involved in the research say the list is expected to grow.

Beyond the number of its schools, Episcopalians and their church “played a uniquely transformative role” in creating the federal government’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School, according to Veronica Pasfield, a Native American researcher and archival consultant. Carlisle became the prototype for U.S. residential schools under Richard Henry Pratt, an Army officer who’d fought Indians on the Great Plains. Episcopalians in the Dakotas reportedly helped recruit students for the school.

“Federal and Church power worked collaboratively to operationalize Indian policy via schools that removed children from home for indoctrination and extraction,” writes Pasfield in a May consulting proposal. She’s now helping guide the church’s boarding school research.

“Indigenous Episcopalians are leading the process to uncover and tell the story of Episcopal Church involvement in Indigenous boarding schools, and that work, as they note, is just beginning,” said Episcopal Church spokesperson Amanda Skofstad in an email. “An apology before thorough research and understanding would fall short of the truth-telling, reckoning, and healing we committed to as a church.”

What emerges, scholars say, could reframe the church’s self-understanding. A traditional view holds that missionary educators had good intentions: to help Native Americans survive and flourish among white settlers by embracing Christianity, learning to own property individually, and developing marketable skills. But such assumed benevolence needs to be questioned, according to Farina King, associate professor of Native American studies at the University of Oklahoma.

“It’s pulling down the narrative that was pushed for so long that these schools were all for the benefit of the people and the children,” said King, a citizen of Navajo Nation and author of “The Earth Memory Compass: Diné Landscapes and Education in the Twentieth Century.” “They were not what they pretended to be: for the good of Native peoples. They were really for the good of the dominating white American officials and Christian leaders.”

To grow enrollment at Carlisle, which garnered funding on a per-pupil basis, Pratt recruited Sioux students in South Dakota with high-pressure tactics and help from church leadership, according to historian David Wallace Adams in “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928.”

Episcopalian titans of industry, including the Vanderbilts, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan, also benefited from the policy that included schools, building “opulent mansions from the profits of their railroads and extractive businesses on lands recently cleared of Indian people,” writes Pasfield, whose great-grandmother attended Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial School in Michigan.

“Indian boarding schools were tools for U.S. nation-building,” Pasfield writes. “They funded the reach and enhanced the wealth of Christian missions. As the archives show, boarding schools were a tool for dispossessing Indian families and impoverishing the future of Indian children and communities.”

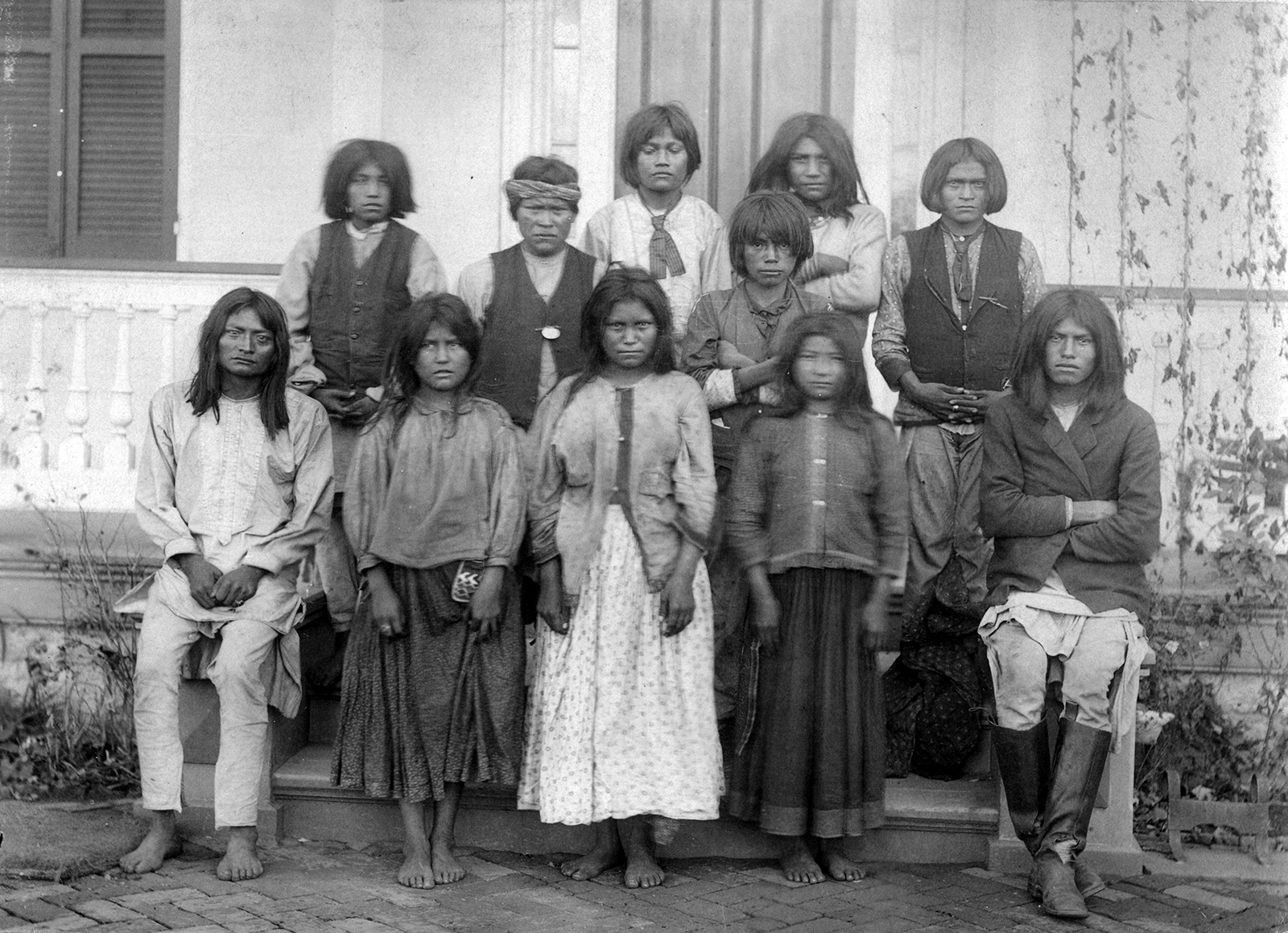

Native American (Chiricahua Apache) boys and girls pose outdoors at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa., after their arrival from Fort Marion, Fla., in November 1886. (Photo by J. N. Choate/Creative Commons)

Some regard what happened through the schools as attempted genocide that merely traded the costly warfare of an earlier time for cultural erasure in schools. Leora Tadgerson, an Indigenous Episcopalian who chairs one of the commissions, refers to the boarding school period as “the genocidal era.”

Pearl Chanar, an Athabaskan tribal member and co-chair of one of the two commissions, believes it all needs to come out, no matter how complicated, shameful, or mixed the history might be.

“In order for everyone to heal, number one: The church has to acknowledge and apologize for what happened,” said Chanar, who lives in Anchorage, Alaska. “And number two: They have to do something about it. They can’t just receive the report, look at it, and do nothing.”

Chanar attended a government-run boarding school in the 1960s, taking four flights on small aircrafts from her Athabaskan village of Minto, Alaska, to reach the island town of Sitka. With no phone available, the teenage Chanar wouldn’t speak to her parents again for nine months.

At Mount Edgecumbe High School, she made lifelong friends from all over Alaska and received an education that would have been impossible back home, where there was no electricity and no high school, though each summer Chanar went back for a season of “hunting, fishing and living off the land.”

Despite the benefits, boarding school could be “really lonely,” she recalled. Her Athabaskan language skills deteriorated and she missed taking part in traditional events such as a memorial potlatch with singing and dancing to honor deceased loved ones.

“Those things that we did in the village — we couldn’t do that anymore,” Chenar said.

Now, she wants everyone with a story to be heard. She wants land returned, especially if it came from Indians and is no longer used as a church school. And because boarding schools often buried children lost to tuberculosis outbreaks and other causes, she wants all their remains located, exhumed, and returned to families.

“If we don’t do this work, then what will happen?” Chenar said. “Will they just remain out there and a shopping mall will be built over them? Somebody’s got to be their voice. And if nobody’s going to step up, then yeah. I’m here. I have a voice. I’ll speak for them.”

The quest is rife with challenges. Locating records in obscure archives will require tenacity. Layers of church bureaucracy could cause delays, Chenar said, if approvals take a long time to get. In most regions where records were sought in the past, access was denied, according to Tadgerson. Advocacy for the work and why it matters will be an ongoing priority.

But commission chairs say they’re encouraged by the bishops’ initial responses. Many have offered to help in whatever way is needed, Chenar said. Meanwhile, community talking circles and panels are cropping up to help get testimonies on record, according to Tadgerson.

“Now that so many individual churches and religious leadership stakeholders are choosing to listen and support survivors and their loved ones,” Tadgerson said in an email, “restorative justice research can begin.”