This year has been called “the year of democracy.” People in more than 65 countries — and comprising more than half of the world’s population — will head to the polls at some point in 2024 to vote for their leaders. Of course, just because a country is holding an election doesn’t mean it’s actually a democracy. Like in Russia, where authoritarian ruler Vladimir Putin “won” 88% of the vote in his reelection bid after changing the constitution to make himself eligible for another term and barring some candidates from running (like dissident Alexei Navalny, who then died in prison).

Another place where an election was held without democracy occurred last month in Venezuela. President Nicolás Maduro, in office since the 2013 death of his predecessor Hugo Chávez, sought a third term. The nation experienced significant democratic backsliding during his previous two terms as his party packed the nation’s high court and overturned some legislative election losses. Maduro’s previous reelection bid in 2018 came after some opposition parties were banned and amid election irregularities that led most of the international community to dismiss it as fraudulent. Many nations even recognized an opposition leader as acting president (but he now lives in exile in Florida).

This year’s presidential election on July 28 was even worse. Once again, some candidates were barred from running. Other politicians experienced death threats and even physical attacks for opposing Maduro. All of the polls conducted showed opposition candidate Edmundo González leading by a large margin, with more than 60% support compared to Maduro’s level with less than 30%. Two independent companies conducted exit polls on election day, with both finding González winning 65% of the vote. Yet, the National Electoral Council overseeing the election announced results the next day showing Maduro winning with 51.2% of the vote — but they refused to release data to justify the reported numbers. Opposition parties rejected the government’s numbers and instead claimed victory. And international groups quickly disputed the government’s claims.

“Venezuela’s 2024 presidential election did not meet international standards of electoral integrity and cannot be considered democratic,” the Carter Center, which had a team in Venezuela to observe the election, declared two days after the election in a statement noting numerous problems with the election process and reported results.

Harvard political scientist Steve Levitsky similarly dismissed the results as “one of the most egregious electoral frauds in modern Latin American history.” U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said there’s “overwhelming evidence” González won. More countries in the region announced they too believe González won, while authoritarian regimes in countries like Cuba and Russia congratulated Maduro on securing another six-year term.

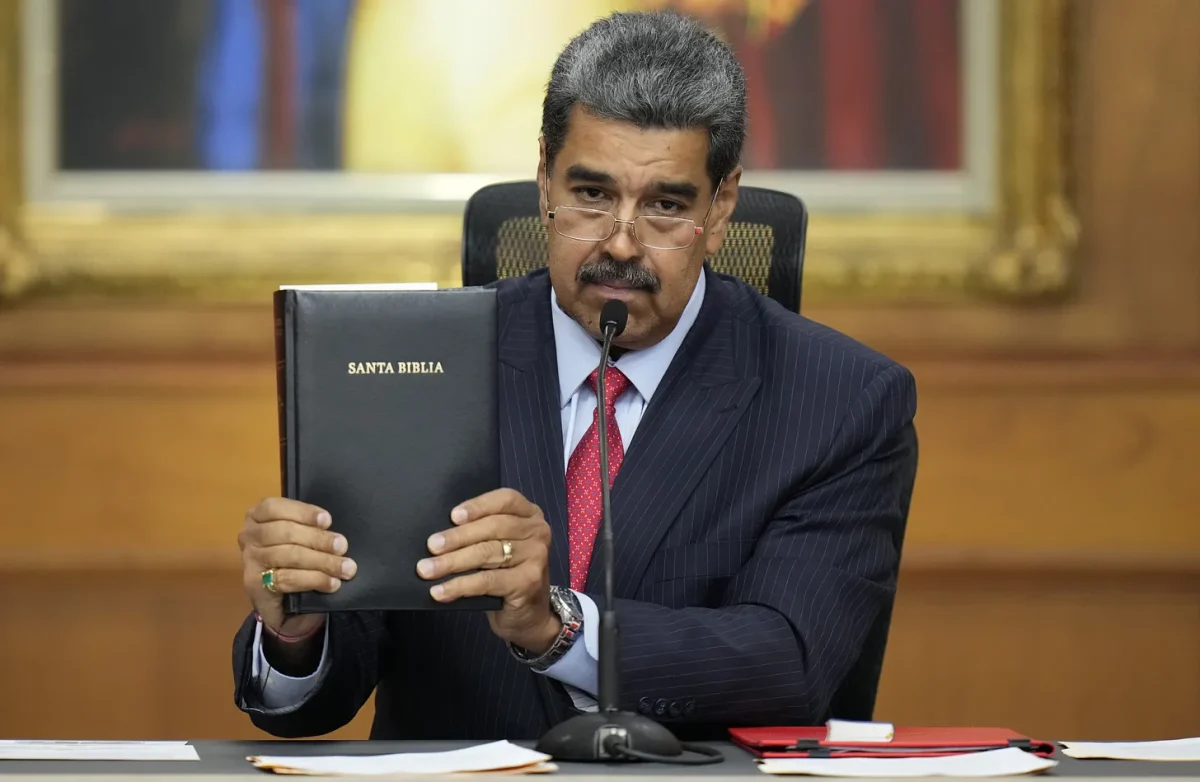

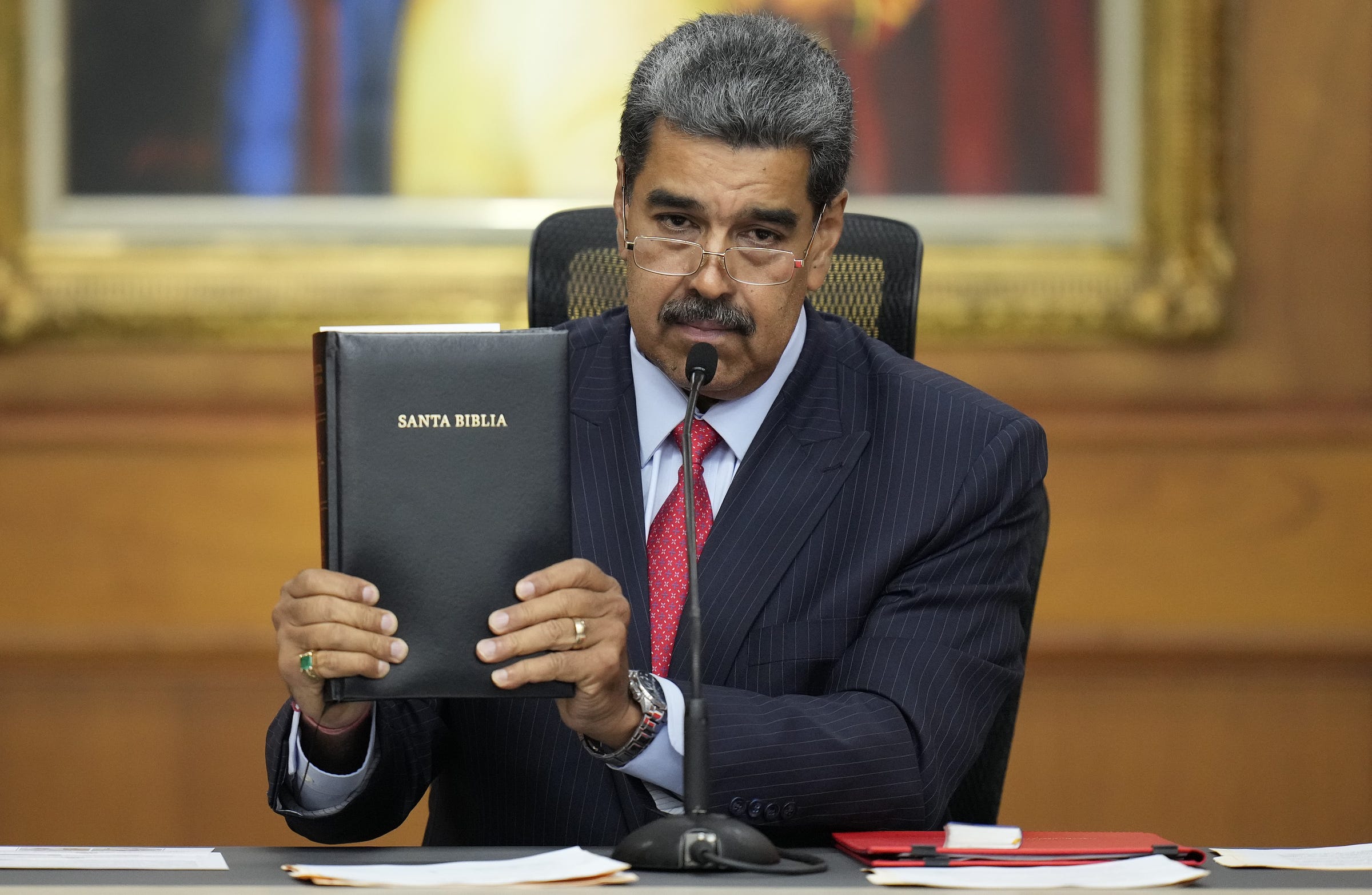

After the fraudulent results, thousands of protesters took to the streets. In the first two days, more than a dozen people died and about 1,000 were detained by police and military personnel. Maduro claimed the protests were a coup attempt against him, which he says justifies the increased police measures he ordered. So with pressure mounting on the streets and from international embassies, Maduro held a press conference three days after the election to insist he won and to accuse the U.S. of trying to topple him. And what did he bring as support?

A Bible.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro holds a Bible during his news conference at Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela, on July 31, 2024, three days after his disputed reelection. (Matias Delacroix/Associated Press)

In a little-noticed moment, especially here in the U.S., a socialist ruler stealing an election and cracking down on protesters opened up a Bible and read from the words of Jesus to justify his own political claims to power. This move came after a campaign where he courted the support of evangelical voters. So this issue of A Public Witness treks to Latin America to consider the dangers arising from the political co-opting of sacred texts.

Seeking Political Salvation

Recognizing the growing unpopularity of his regime amid economic crises — which has gotten so bad that estimates are that one-fifth of the population left the country in recent years — Maduro knew he needed to do something to save his presidency ahead of last month’s election. So he turned to evangelicals.

Like much of Latin America, Venezuela is a predominately Catholic nation. But the growth of evangelicals in Latin America can also be seen in Venezuela. While evangelicals accounted for just 17% of the population in 2014, some estimates peg them as high as 30% today. With Catholic leaders criticizing his economic policies, Maduro saw evangelicals as an alternative community to help mobilize voters.

The rest of this piece is only available to paid subscribers of the Word&Way e-newsletter A Public Witness. Subscribe today to read this essay and all previous issues, and receive future ones in your inbox.