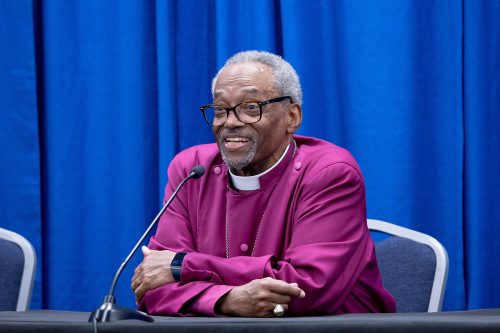

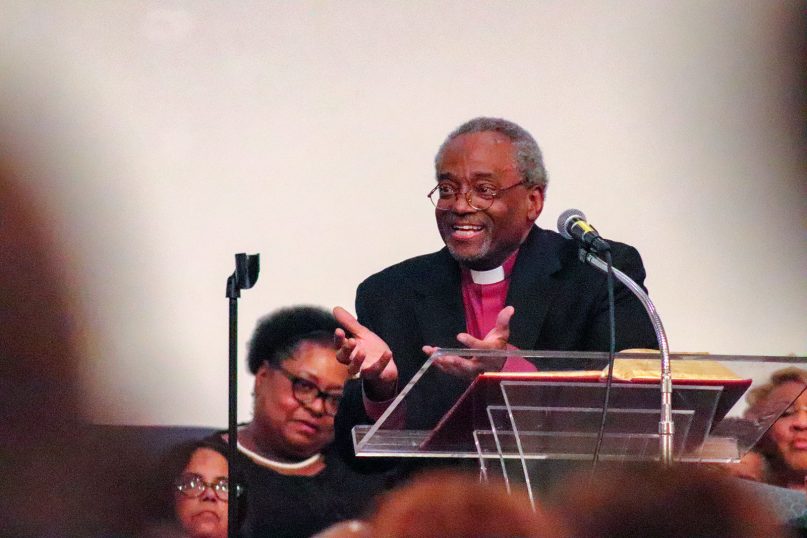

(RNS) — Bishop Michael Curry may best be remembered for his electrifying sermon on the power of love at the 2018 royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. To Episcopalians who knew Curry as their presiding bishop, his turn on the world stage was merely recognition of Curry’s rock star preaching skills. Fluent in a Black preaching tradition, he is able to captivate both the well-heeled and the working class.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry addresses the media at the Episcopal Church General Convention in Louisville, Ky., June 26, 2024. (Photo by Randall Gornowich)

But when COVID-19 hit and churches closed, Episcopalians also saw his down-to-earth skills of improvisation. Staffers at the denomination’s New York headquarters had appealed to the boss to deliver his online Easter message from a local church, using a stained-glass window as a backdrop.

Curry, never big on pomp and circumstance, said a church would be unnecessary: He was fine delivering the message from his home study in Raleigh, North Carolina. He gave his Easter 2021 sermon from his desk, with a tableau of family photos and a red Buffalo Bills helmet perched atop a stack of books behind him. He spoke directly, fireside-chat-like, about wanting to meet Mary Magdalene in heaven.

On Thursday (Oct. 31), Curry, 71, completed his nine-year term as presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, and it’s his casual style and his capacity to adapt and improvise that may be his signature, even more than his historic election as the first African American to lead a mostly white denomination. The most beloved presiding bishop of recent decades, he has an easy manner that helped the church weather a period of rapid change.

Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry preaches during a revival at Harvest Assembly Baptist Church in Alexandria, Va., on March 6, 2019. (RNS photo/Adelle M. Banks)

“There’s a hymn that has a verse in it that says ‘New occasions teach new duties; Time makes ancient good uncouth,’” he said, citing from memory a 19th-century poem by James Russell Lowell, an ardent abolitionist.

“You have to learn new realities, you have to take the ancient principles and you’ve got to apply them in new ways,” Curry said.

Curry doesn’t rue the decades-long denominational decline that has affected mainline Protestant denominations, including his own. Under his watch the Episcopal Church lost some 300,000 members, going from 1.9 million members in 2015 to just below 1.6 million in 2022, the latest year for which figures are available.

He pointed out that social forces beyond the Episcopal Church are at work and said he believed the church should not expect the future to look like the past.

Speaking to RNS via Zoom from his home, his preferred way of communicating, Curry, who has suffered a series of health challenges in the past few years, recalled that his mission was to remind Episcopalians that they are a part of a Jesus movement more than they are part of an institution. The institution should be designed to serve the movement, not the other way around.

His successor appears to have gotten the message. On Saturday, Sean Rowe will be installed as the 28th presiding bishop in a smaller, simpler service with less than 130 people present and everyone else watching on a livestream.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry, center, introduces Bishop Sean Rowe, right, the presiding bishop-elect of the Episcopal Church, during the denomination’s General Convention in Louisville, Ky., June 26, 2024. (Photo by Randall Gornowich)

Curry is proud of some of his administrative accomplishments, most notably the creation of the Episcopal Coalition for Racial Equity and Justice, a voluntary organization charged with dismantling white supremacy across the denomination. He acknowledged that he has not escaped criticism for administrative missteps: Curry is the subject of an internal clergy misconduct complaint for his response to abuse allegations against a former Michigan bishop alleged to have physically and emotionally abused his now ex-wife and sons.

But as presiding bishop Curry set for himself a larger goal — serving as evangelist in chief, drawing the church back to its core gospel message: Jesus’ lesson on love.

“I think people will look back at Michael’s time and say he reminded us that it was about loving God, loving each other, and loving ourselves while we’re at it,” said the Rev. Chuck Robertson, canon, or assistant, to the presiding bishop for ministry beyond the Episcopal Church. “He’s really serious about that. If it’s not about love, it is not about God.”

Love was, of course, the theme of his now famous address at Windsor Castle during the royal wedding, in which he implored listeners to reconsider the power of love in every facet of life.

“We were made by a power of love,” he said. “And our lives were meant and are meant to be lived in that love. That’s why we are here.”

In his 13-minute address, he managed to quote the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the French Jesuit theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, in addition to the Song of Songs and the Prophet Amos.

Curry said the invitation to speak at the wedding was such a surprise that he thought it might be an April Fool’s joke. Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby, the head of the Anglican Communion, extended the invitation, with a question: “If you were asked to give the address, would you be willing to do it?”

The May 19, 2018, sermon made him a star far beyond the Episcopal Church. Robertson said that wherever Curry travels — and he has traveled to all its dioceses or regional groups with the exception of one in Venezuela — people crowd around him with requests for selfies, a handshake, or a hug. A self-described “people person” with an easy smile and laugh, Curry gladly obliges.

He is now appearing in a documentary, “A Case for Love,” that explores whether unselfish love is really possible.

Friends and colleagues say Curry’s genial and folksy manner should not be mistaken for superficiality. The Rev. Elizabeth Eaton, presiding bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, who has become a trusted colleague as their two denominations have increasingly worked together, said Curry is a deep and unflinching Christian.

“Under all of that gentleness and good humor that he shows, he is a strong, strong voice for what we believe to be the message of the gospel, which is inclusion, God’s love for everyone, and the promise of liberation and new life,” Eaton said.

Presiding Episcopal Bishop Michael Curry. (Photo courtesy of the Episcopal Church)

The latter part of his tenure was inhibited in part by a series of health scares. The latest came in March, when he received a pacemaker as part of ongoing treatment for an irregular heartbeat. Last year, doctors diagnosed him with a cerebral hematoma, or brain bleed, likely caused by a fall at a church event. He said he was on new medication and feeling well.

In his last days in office, Curry attended a series of transition meetings, including a farewell Eucharist with his staff. In June, the denomination’s House of Bishops feted him with a tribute dinner and a set of tickets to a Buffalo Bills game, along with a jersey with his name printed on it. (Curry, the son of an Episcopal priest, has been a lifelong fan since growing up in Buffalo, New York.)

In retirement, Curry said, he and his wife, Sharon, plan to stay in North Carolina, which they never really left, only occasionally occupying the presiding bishop’s residence above the New York headquarters. Curry’s maternal grandmother was a Baptist from eastern North Carolina, and after his mother died when he was a boy, Curry spent many summers there. He later served as bishop of the state’s Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina from 2000 to 2015.

Curry said his most immediate plan is to get a dog, which he has already announced he will name Buddy. He said he wants to do “stuff that matters” but he hasn’t decided yet what that will be.

Earlier this week he and his wife cast their ballots in early voting. He has spoken out forcefully against Christian nationalism and remains hopeful about the future.

“Benjamin Elijah Mays, who used to be the president of Morehouse College, used to say, faith is taking your best step and then leaving the rest to God,” Curry said. “And there’s a lot of wisdom embedded in that. The alternative — to submit and give up — is unthinkable. We cannot and must not give up on hope for this world.”