Earlier this month, the family of Cameron Lamb marked the fifth anniversary of when he was killed — while unarmed on his own property — by a Kansas City, Missouri, police officer. This week, the pain of the person missing from the Christmas celebrations will be magnified by the news on Friday (Dec. 20) that Missouri’s governor freed Lamb’s killer. Clergy in the state quickly denounced the governor’s action.

Before George Floyd’s killing sparked global protests, a White police officer in Kansas City killed an unarmed Black man within seconds of breaking into the man’s property, blocked emergency personnel from assisting the victim, and planted a gun to justify the shooting. After the Dec. 3, 2019, killing of the 26-year-old Lamb, detective Eric DeValkenaere became the first Kansas City officer convicted of killing a Black man. But late on Friday, outgoing Republican Gov. Mike Parson commuted DeValkenaere’s sentence to free him after just 14 months in prison.

Although Parson, a former sheriff, had long hinted he would take action to reverse DeValkenaere’s conviction (as had his incoming successor, Lt. Gov. Mike Kehoe), the move still warranted sharp rebukes from prominent Black ministers in the state. Rev. Emanuel Cleaver III, senior pastor at St. James United Methodist Church in Kansas City, told me Parson’s decision “perverted justice” and shows that the governor “must not understand that this is the season where God gave the gift of love.”

“The governor’s decision to free DeValkenaere will only widen the gap that has existed between law enforcement and the Black community that goes back generations,” Cleaver added. “What it says to the community is that it is okay to kill as long as the victim is Black. It is a complete disregard and disrespect for Cameron Lamb’s family.”

Laurie Bey (center), the mother of Cameron Lamb, and Merlon Ragland (right) wear shirts honoring Lamb at the Lincoln Memorial as final preparations are made for the March on Washington in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 28, 2020. (Jonathan Ernst/Pool via AP)

Similarly, Rev. Darryl Gray, senior pastor of the Greater Fairfax Missionary Baptist Church in St. Louis, told me that Parson’s commutation of DeValkenaere was “not justice” but “unconscionable” and “a travesty.”

“This move was intended to speak very clearly and loudly that Black lives do not matter in the state of Missouri,” added Gray, who is also the director general for the social justice commission of the Progressive National Baptist Convention.

Other Black pastors across the state also denounced the move by Parson, a White Southern Baptist who has claimed his faith impacts how he governs. The timing of Parson’s action particularly drew criticism from clergy and other advocates. As Nimrod Chapel, president of the Missouri State Conference of the NAACP, declared, “The release of this killer in the name of Christmas is sure backwards.”

Get cutting-edge reporting and analysis like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

‘Double Standard’

Cleaver and Gray had previously joined other clergy from multiple denominations in backing a statement from the Missouri NAACP criticizing Parson’s expected move to free DeValkenaere. The statement highlights Parson’s “double standard” of “picking and choosing when to trust” the justice system.

For instance, Parson ignored pleas from the NAACP, clergy, and activists across the state and around the country as he refused to commute or pardon Marcellus “Khaliifah” Williams, who was on death row. Parson’s predecessor, Republican Gov. Eric Greitens, had halted a previous execution date for Williams and set up a panel of five former judges to investigate the possibility of Williams’s innocence. However, Parson dissolved the state board of inquiry and refused to release its findings. The state executed Williams in September despite corrupted evidence and prosecutors trying to free him. The NAACP put it simply: “Tonight, Missouri lynched another innocent Black man. Gov. Parson had the responsibility to save this innocent life, and he didn’t.”

Parson justified his refusal to stop Williams’s execution by declaring his trust in the system: “When it comes down to it, I follow the law and trust the integrity of our judicial system.” He added that Williams had numerous hearings but “no jury nor court” had ruled to free him.

Yet, as the state NAACP statement notes, all of that could also be said about DeValkenaere. The judicial system found him guilty and sent him to prison — after allowing him to remain free on bond for two years as he exhausted his appeals. Three Parson-appointed appeals court judges upheld the verdict and the state Supreme Court let it stand. Additionally, a federal judge in an ongoing civil suit filed by Lamb’s family against the former officer ruled that DeValkenaere violated Lamb’s Fourth Amendment rights by unlawfully going onto Lamb’s private property.

“We have already watched as those with connections and privilege avoid accountability, leaving families and communities to grieve without closure or justice,” the Missouri NAACP’s statement offers. “Where is justice for Cameron Lamb? Where is justice for his family and friends, who continue to carry the weight of this loss?”

Parson refused to consider innocence claims in Williams’s case by insisting he had “trust” in judicial system. But then he didn’t trust that same system — or judges he appointed — in the case of DeValkenaere. The double standard doesn’t end there. Parson’s “trust” in the judicial system can often be defined in Black-and-White terms.

As governor, Parson oversaw 13 state executions, repeatedly refusing to consider clemency because of his “trust” in the judicial system. Additionally, he refused to free multiple Black men sitting in prison for decades while innocent. Like Lamar Johnson, who spent 28 years in prison on a wrongful conviction before being released in 2023 and Kevin Strickland who spent 43 years in prison after a wrongful conviction before being released in 2021. In both cases, Parson refused to give a pardon or commutation even after prosecutors and judges declared the men innocent, thus prolonging their unjust incarcerations until the system finally freed them without the governor’s assistance.

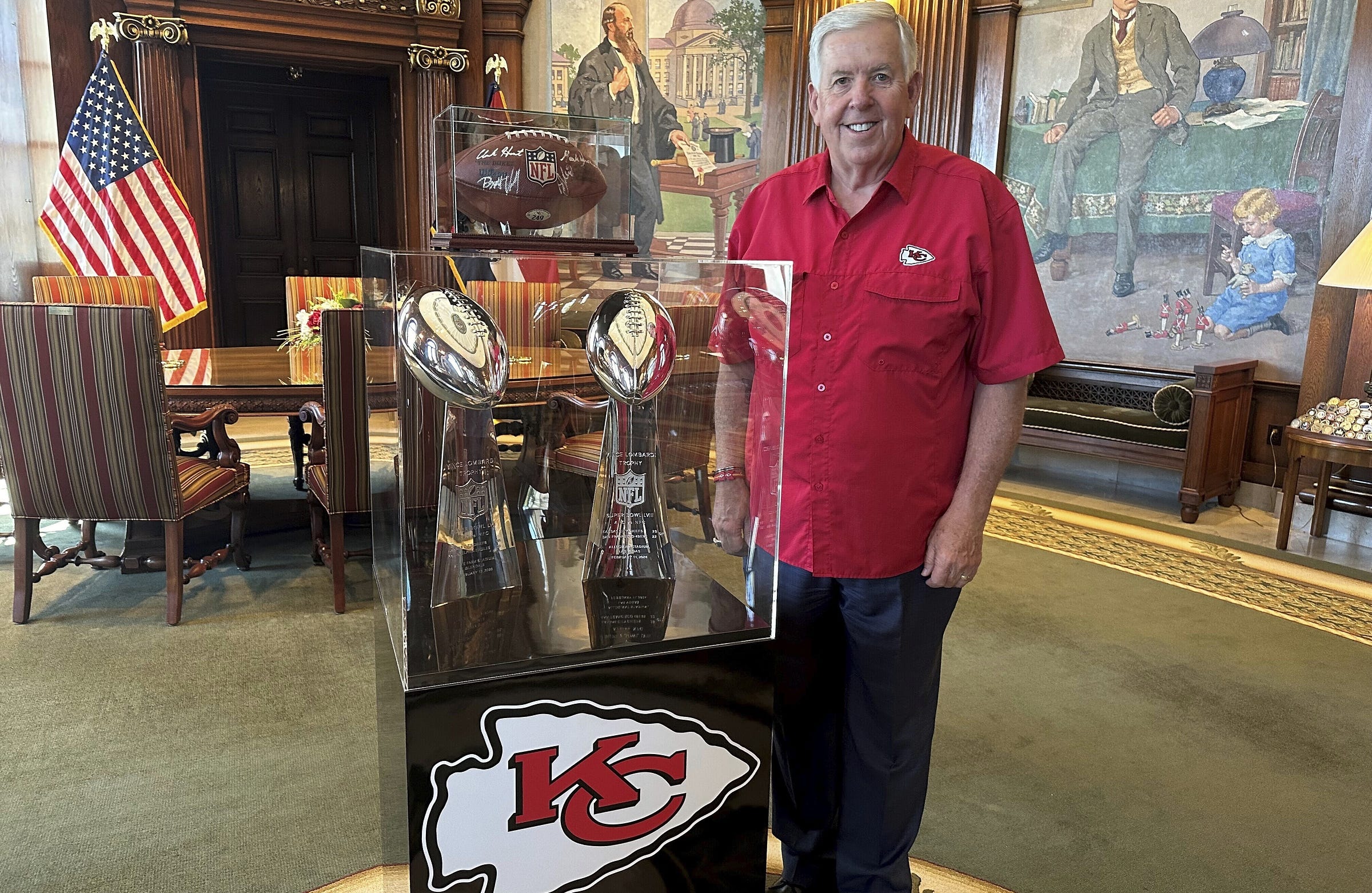

But while Parson refused to free innocent Black men, he did find other cases where he decided not to trust the legal system. In 2021, he pardoned a wealthy White couple who had pleaded guilty after wielding guns to threaten peaceful Black Lives Matter demonstrators. Earlier this year, he commuted the sentence of Britt Reid, a son of Kansas City Chiefs head coach Andy Reid, who had been an assistant coach for the team when he drove while intoxicated and severely injured a five-year-old girl (who spent 11 days in a coma and suffers from a lifelong traumatic brain injury). Parson, who has a Chiefs tattoo, has attended all three of the team’s Super Bowl wins during his tenure in office.

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson poses next to the two most recent Super Bowl trophies of the Kansas City Chiefs, on display in his Capitol office in Jefferson City, Missouri, on June 27, 2024. (David A. Lieb/Associated Press)

An ‘Unjust’ Ruler at Christmas

The prosecutor who led the conviction of DeValkenaere criticized Parson’s commutation as a miscarriage of justice “based on a false narrative.” She had previously urged Parson to speak with Lamb’s family before taking any action on the case, but the governor did not do so. Parson was similarly criticized in the Reid case for not talking with the victim’s family before issuing a commutation. The prosecutor who led the trials against both DeValkenaere and Reid is not the only one who criticized the governor for adding to the pain of Lamb’s family.

“The legal process by which the killer of Cameron Lamb was convicted clearly voiced how the people of Missouri collectively said Cameron Lamb’s life mattered,” Rev. Darron Edwards Sr., lead pastor at United Believers Community Church in Kansas City (and a Word&Way board member), told me. “Why would a governor go against the legal system? Why didn’t the governor communicate his sovereign decision to the affected family prior to a public statement of commutation? Why is it that empathy, compassion, and transparency fail to appear in lines of communication where we espouse that there should be bridges of relationship built between communities and governmental entities?”

“After speaking with the Lamb family, I was reminded again of their words, ‘It’s hard to build a bridge when the other side constantly throws up a wall,’” added Edwards, who has worked to build bridges between the police and his community while also criticizing police killings of Black men. “I do believe in the resilience of Kansas City and its ability to come together in the face of challenges. It is my steadfast hope that this will be a moment where we choose unity and progress over division.”

The family of Lamb had planned to take their annual Christmas picture on Dec. 4, 2019. But after he was killed the day before, they canceled the studio appointment. His mother recently said she had been unable to continue the tradition of Christmas photos until finally having one made this year.

“I just have not been in a place where I felt like I wanted to do that, because of the void in not having my son,” Laurie Bey, his mother, said. “This right here, it’s a start, but it’s still because we’re going to look at these pictures and we’re going to know that he should be in this photo with us.”

As Lamb’s family tries to rebuild their Christmas traditions, clergy in the state criticized Parson for his commutation at the same time the governor puts on a big show about celebrating Christmas. The Governor’s Mansion hosts a 30-foot Christmas tree and lots of decorations inside and out, he declared December official “Christmas Tree Month” in Missouri, and he invited people for candlelight tours of the mansion with the theme “A Christmas Hug: The Farewell to the Parson Family.” But he oversaw a state execution on the third day of Advent and released an unrepentant police officer who killed an unarmed man on the 20th day.

Ornaments featuring guns on the Christmas tree in the Missouri Governor’s Office. (Office of Missouri Governor/Public Domain)

“For two years, Eric DeValkenaere lived at home with his family while 26-year-old Cameron Lamb lay in a cold grave,” Rev. Traci Blackmon, a United Church of Christ minister in St. Louis, told me. “During this season of Advent, I am mindful that while it was indeed lawful for Gov. Mike Parson to use his waning power to commute the sentence of a convicted killer, it was unjust. A ruler with waning power also acted unjustly during the first Christmas season, and justice still came. Gov. Parson has sent Eric DeValkenaere back home in time for Christmas, but he cannot set him free.”

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor