(RNS) — At a recent congregational meeting, members of Columbus Mennonite Church in Ohio’s state capital gathered to figure out how they might respond to President-elect Trump’s call to enact “the largest deportation” in U.S. history.

The church has long been a part of the sanctuary movement, which offers shelter for undocumented immigrants who might otherwise be deported. During Trump’s first term, the Mennonites in Columbus gave a woman with a deportation order a place of refuge for more than three years. Now, church members wanted to consider how their ministry to migrants might look in a second Trump term.

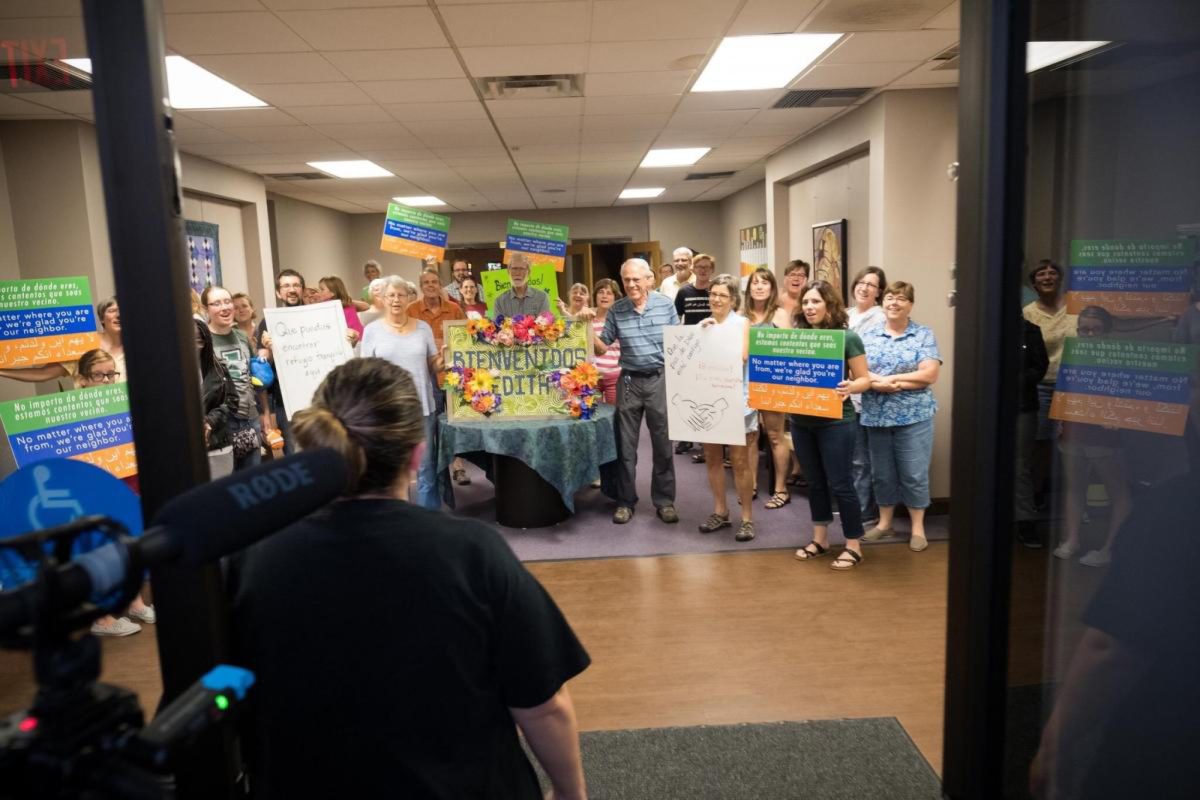

Edith Espinal arrives at Columbus Mennonite Church in Columbus, Ohio, to take sanctuary on Oct. 2, 2017. (Photo courtesy Columbus Mennonite Church)

Before they broke into groups for discussion, the congregants heard about the history of the sanctuary movement since the 1980s. They also heard from immigration lawyers about Immigration and Customs Enforcement policies that since 2011 have discouraged agents from making arrests at churches.

NBC News recently reported that Trump plans to rescind the policy on his first day in office.

At the end of the evening, a straw poll was taken and found broad support for continuing to provide immigrants with housing, but less support for sanctuary.

“Sanctuary just seems like a less safe strategy this time around,” concluded the Rev. Joel Miller, the church’s pastor.

In November, a group of North Carolina church pastors who had also offered sanctuary to undocumented immigrants during Trump’s first term reached the same conclusion.

“We were all like, we just don’t feel we can tell someone entering into sanctuary right now that we could keep them safe,” said the Rev. Isaac Villegas, the former pastor of Chapel Hill Mennonite Fellowship, who attended the meeting.

During Trump’s first term, 71 undocumented immigrants with deportation orders publicly announced that they had taken sanctuary in churches across the country. Other churches may have taken in undocumented immigrants secretly, making exact numbers impossible to know.

Now, with Trump’s aggressive calls for a mass deportation targeting millions of immigrants living in the U.S., and with threats to rescind a policy that kept immigration officials from raiding churches, many congregations are feeling less certain about sanctuary.

The success of the sanctuary movement during Trump’s first term — limited as it was — lay in the fact that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents never set foot on church grounds.

ICE agents, for the most part, respected a 2011 policy that discouraged its agents from conducting raids at so-called “sensitive locations” — churches, schools, and hospitals. (Instead, they impose fines of hundreds of thousands of dollars on nine people in sanctuary for disobeying orders to leave the country. Most of those were reversed.)

In 2021, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas updated that policy, making it clear that churches, schools and hospitals (but also playgrounds, childcare centers, and emergency shelters) were not just “sensitive locations” but “protected areas” where ICE searches and arrests are discouraged, except in certain cases where there is imminent risk of death or physical harm or a terrorist attack.

Trump’s threat to set aside the policy is chilling the passions felt by many houses of worship for what proved to be a successful tool of resistance.

In public sanctuary cases, churches were upfront about who they were sheltering. They typically held press conferences or issued press releases informing the community — and, critically, ICE — who they were taking in to sanctuary.

“What’s difficult about the public sanctuary is you’re essentially bringing people out in the open into the media,” said the Rev. Noel Andersen, national field director at Church World Service, who helps organize and advocate for sanctuary. “But if that’s not going to help their case, then that’s not necessarily something we want to do.”

It may, however, be too soon to conclude that the protective areas memo will in fact be rescinded, said David Bennion, an immigration lawyer and the executive director of the Free Migration Project.

“I’ve seen some people saying don’t obey in advance, don’t concede before the thing has even been done, and I would apply that to this as well,” Bennion said.

Bennion pointed out that the protected areas policy is not law to begin with, but guidance. ICE’s actions will continue to be informed by political considerations, such as whether the public would support a raid on a church property.

“They’re subject to press and public opinion in a way that they wouldn’t be if this were an actual law or regulation, which it’s not,” Bennion said.

Churches, such as Columbus Mennonite, are now weighing all the options.

Church members embraced their sanctuary recipient, Edith Espinal, a mother of three, and worked around the clock to protect her from deportation. Espinal left sanctuary on Feb. 18, 2021 — as soon as the new Biden administration issued new guidelines stating she was no longer a priority for deportation.

Miller, the church’s pastor, said Espinal still visits the church for Sunday services on occasion and remains beloved by many in the church.

Her apartment, which the church created in an unused preschool area on the second floor of the building, is still being put to good use. Two asylum seekers, one from Africa, one from South America, lived in the apartment in the last couple of years. It is now occupied temporarily by a Haitian refugee.

Who its future occupant might be remains to be seen. The church of about 180 members is committed to the holy work of “being sanctuary people for one another.”

“We’re actively talking and preparing,” Miller said. “But a lot is unknown.”