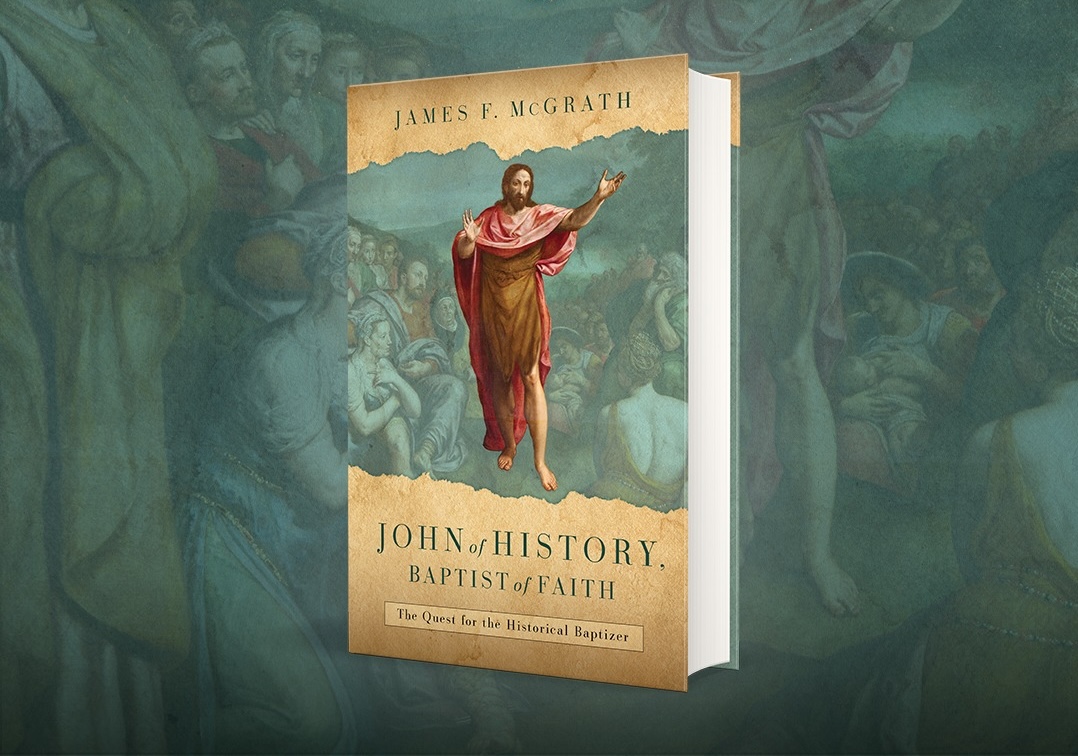

JOHN OF HISTORY, BAPTIST OF FAITH: The Quest for the Historical Baptizer. By James F. McGrath. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2024. Xiii + 438 pages.

Who is John the Baptist? We encounter him during Advent, Epiphany, and at other points in the church year. During Advent, we recognize John as the one who prepares the way for God’s chosen one. He’s the cousin, so it seems, of Jesus (in Luke), and he’s the one who Baptizes Jesus in the Jordan (it is appropriate that this review appears the week preceding Baptism of Jesus Sunday). While John’s role in the Gospels is subservient to the Gospel focus on Jesus, surely there is more to the story of John the Baptist than what these brief mentions suggest. According to James McGrath, there is much more to say about John, it just takes a bit of digging to discover it.

Robert D. Cornwall

McGrath’s book John of History, Baptist of Faith is a companion to his book Christmaker: A Life of John the Baptist (Eerdmans, 2024), which came out from Eerdmans months apart. Regarding the author, James McGrath teaches religion, with a focus on the New Testament, at Butler University (Indianapolis, Indiana). John of History, Baptist of Faith is the more “academic” of the two volumes, but they fit well together. Christmaker offers a macro-level picture of the one we know as John the Baptist and of the two, it is the more accessible. If Christmaker provides a picture of the forest as a whole, John of History, Baptist of Faith examines the trees themselves. The latter volume is written for the scholar, though it will have value as a reference work for the nonspecialist (that would include me).

At points, McGrath’s attempt to reconstruct the story of John the Baptist, as told in both volumes, is speculative. He draws upon a variety of sources, from the New Testament to Mandean sources. Not everyone agrees with his interpretation of the evidence, but he does open up numerous avenues for further exploration. As a reviewer, I will confess that I am not fully conversant with all the different elements of the picture that McGrath seeks to paint of John’s life and work. Therefore, in this review I offer a nonspecialist’s take on the book, leaving to those with more expertise the job of dissecting the message of the book, and the specialists will dissect it (as I got to witness at the 2024 Society of Biblical Literature session that focused on this book). I will let James speak about his experience at the session!

Concerning the book itself, as I read it, McGrath points out in his introduction that “Despite there being a significant amount of agreement that John the Baptist played a formative role in the Christian tradition, he has remained a figure shrouded in mystery.” Gaining a clearer picture, however, has been difficult. Part of the reason for this is that Christian tradition, including the Gospels themselves, tends to elevate Jesus and subordinate John (p. 1). In writing these two volumes, McGrath wants to dig below the surface to discover the John of history who lies behind the John we meet in the gospels. As noted earlier, while Christmaker tells the macro story, in this volume McGrath seeks to provide evidence for the claims made in the first book. For most of us, John of History, Baptist of Faith will serve as a supplement to Christmaker, providing the evidence that is needed to more fully understand why McGrath makes the claims he makes in Christmaker. Together they serve McGrath’s purpose to offer us a more historical picture of John.

As I noted earlier, this book focuses on the trees rather than the forest. He begins by exploring what Q (the sayings source scholars believe Matthew and Luke used to write their versions of the story of Jesus) has to say about John (Chapter 1). In “John the Baptist in Q,” McGrath draws on a reconstructed Q source, suggesting that John appears more frequently in Q than we may suppose. The point here is that if Jesus was John’s follower and successor, as McGrath believers, it is likely that some elements used to describe Jesus originally could have been ascribed to John. Thus, Q might have much to say about John’s teachings, which McGrath believes Jesus picked up and expanded upon. If that is true, then the two figures — John and Jesus — were intertwined in ways we might always recognize.

After he discusses John in Q, McGrath describes a second set of sources that are not often appealed to by biblical scholars in their attempt to reconstruct John’s life, and these are the Mandaean sources. We learn here that the Mandaeans hold John in the highest regard, placing him above Jesus, whom they view with a certain amount of hostility. Thus, in Chapter 2, titled “The Usefulness of Mandaean Sources,” McGrath suggests that while the Mandean sources are later than the New Testament sources, the Mandaean sources need to be taken seriously because they offer us important nuggets that can help us reconstruct the John of History. However, they must be read critically. Nevertheless, if read in that fashion, they can provide important insights regarding John’s life.

The third chapter is titled “Jesus as John’s Disciple and Witness about Him.” Here McGrath seeks to demonstrate that John was not merely the forerunner of Jesus, but that Jesus was John’s disciple and successor. That is, he seeks to demonstrate from early Christian tradition, that Jesus “followed in his master’s footsteps and carried on not only many of his central emphases and ideas but even his turns of phrase. Building on the case made in chapter 2, here we will also begin to bring Mandaean sources into the picture to see how they confirm and complement what the New Testament tells us” (p. 105). Taking these sources together, McGrath believes he can demonstrate that they show the strong connection between the two figures. By demonstrating the continuity between John and Jesus, McGrath believes he can provide a fuller picture of John.

The fourth chapter is titled “An Ancient Infancy Narrative about John the Baptist.” Here again, McGrath draws on both Mandaean and Christian sources, including the infancy narrative found in the Gospel of Luke. This is important to McGrath’s reconstruction of John’s relationship with his parents, who, he argues, had different visions for his life. Elizabeth dedicated him to God as a perpetual Nazirite, while Zechariah wanted him to follow him into the priesthood. Here McGrath draws on a text known as the Protoevangelium of John to fill in elements of the story, which is controversial. In this chapter McGrath seeks to reconstruct an infancy narrative of John, which is intriguing in itself, applying some of what is said of Jesus to John.

John is known as the Baptist for a reason — he practiced immersion for repentance and forgiveness of sins. Thus, Chapter 5, “The Origin and Meaning of John’s Immersion” explores the question of where John derived this practice from and what it means. McGrath shows that John drew on several sources for his baptismal practice, but what he offered was somewhat unique. What is most controversial about McGrath’s proposal is that John offered baptism as an alternative to the Temple sacrifices as the means of remitting sins. Here again, he points to John’s possible disagreement with his father’s profession. At the same time, he may have drawn from his priestly ancestry as a foundation for his own practice. McGrath also points to connections between John’s baptismal practice and Mandaean baptism, while also pointing out the differences between the two baptisms. For those who do not know much about the Mandaeans, this will be informative. As noted, McGrath believes that Mandaean sources can be of great help in reconstructing John’s life. Therefore, in Chapter 6, McGrath focuses on “Jesus’s Baptism according to the Mandaeans.” He notes that when it comes to the baptism of Jesus, the Mandaean and Biblical sources are quite similar. Interestingly, according to Mandaean sources, Jesus was both a “wise and deceitful Messiah.”

Turning to Chapter 7, McGrath explores the important terminology of “The Son of Man Who Is to Come.” He drills down into the meaning of Jesus’ use of the phrase, whether it is simply another way of speaking of self-identity or is an apocalyptic term, as in Daniel. The central question focuses on what John means when he speaks of one who is stronger than him, and whether John envisioned Jesus filling that role. In McGrath’s view, John’s message about the coming one who is stronger could help us better understand Jesus’ unusual use of the Son of Man phrase.

A further element in this reappraisal and reconstruction of John’s life and ministry is John’s connection to Gnosticism. Therefore, in Chapter 8, McGrath explores “John the Baptist and the Origins of Gnosticism.” McGrath argues that the two are strongly connected, such that several figures connected to Gnosticism, including Simon Magus, were understood to be disciples of John. Of course, Mandaeanism has gnostic elements. That is not to say that John was a gnostic any more than Jesus was, but Gnostics seem to claim him as a founder. Therefore, this is a worthwhile avenue to explore.

Chapter 9 focuses on the “Prayers of John the Baptist.” We might remember that in Luke, Jesus’s disciples ask him to teach them to pray as John taught his disciples. The suggestion made here is that the Lord’s Prayer may reflect some of John’s own prayers. With that in mind, he points to examples of John’s prayers that are found in Mandaean texts and Syriac Christian sources.

The overall message of McGrath’s John of History, Baptist of Faith is that if we take seriously the various sources that speak of John, whether that is the sayings source Q to the Mandaean sources, we can put together a picture of John that will help us better understand John’s sense of identity but also why John and Jesus are so connected. McGrath makes strong claims in both volumes concerning John, much of which can be viewed as speculative. However, McGrath is careful to nuance his views. Although critics (as seen in the SBL presentation) may find his reconstruction overly speculative, for his part, McGrath recognizes that he is making claims that need to be tested. Even if he may be wrong at points, if he can stimulate the conversation, he will consider himself successful. In the end, taken together, Christmaker and John of History, Baptist of Faith, one offering a macro perspective and the other a micro perspective, McGrath’s volumes help us gain a better understanding of this person who is so familiar and yet so unfamiliar. Reading them we may discover why this is true.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.