(RNS) — At cross-cultural gatherings in Bethlehem, West Bank, groups of children and adults turn to a 67-year-old, colorful comic book with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s image on its cover, his tie and shirt collar visible beneath his clerical robe.

As they read from “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story,” the group leader is prepared to discuss questions about achieving peace through nonviolent behavior.

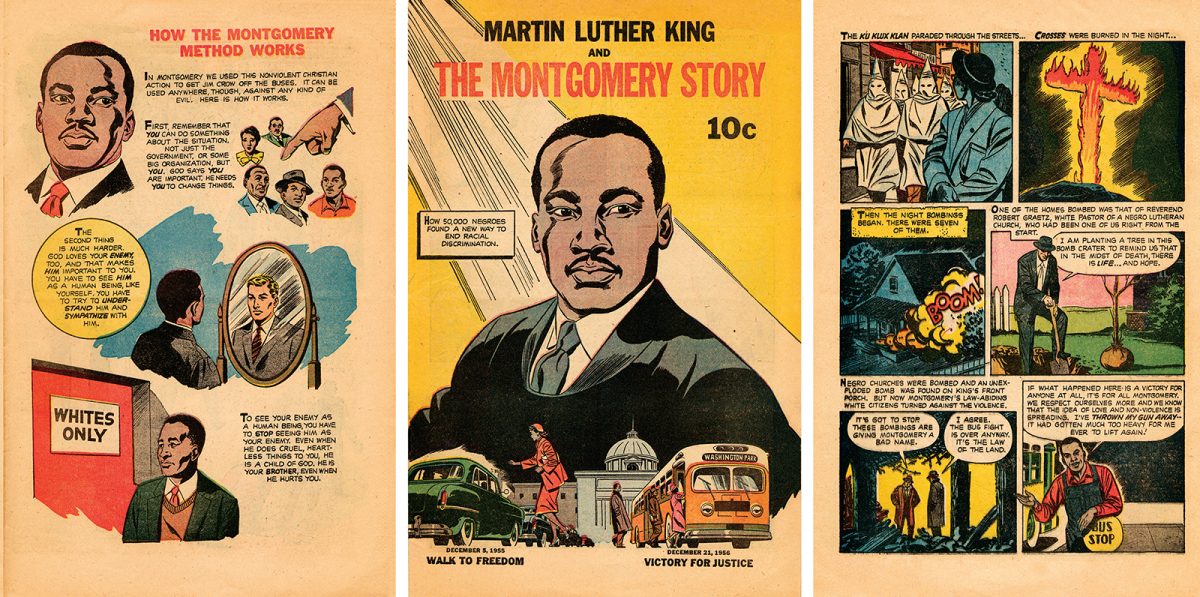

Cover and excerpts of “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story.” (Images courtesy Fellowship of Reconciliation)

“What are the teachings we have from Martin Luther King?” asks Zoughbi Zoughbi, a Palestinian Christian who is the international president of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and founder of Wi’am: The Palestinian Conflict Transformation Center. “How can we benefit from it, and how do we deal with issues like that in the Palestinian area under the Israeli occupation? How to send a message of love, agape with assertiveness, not aggressive?”

Zoughbi told RNS in a phone interview that the comic book, published in 1958, remains a staple in his work, which includes both English and Arabic versions. (It is available in six languages.) Over the decades, it was used in Arabic in the anti-government Arab Spring uprisings, in English in anti-apartheid activism in South Africa, and in Spanish in Latin American ecclesial base communities, or small Catholic groups that meet for social justice activities and Bible study.

It continues to be a teaching tool and an influential historical account in the United States as well. The book was distributed in January at New York’s Riverside Church and has been listed as a curriculum resource for Muslim schools. And it remains a popular item, available online and in print for $2, at the bookstore at Atlanta’s Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. Store director Patricia Sampson called it “one of our best sellers.”

Copies of “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story” are used in teaching at the Palestinian Conflict Transformation Center in Feb. 2025, in Bethlehem, West Bank. (Photo courtesy Zoughbi Zoughbi)

The 16-page book was created by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a Christian-turned-interfaith anti-war organization. It was written by Alfred Hassler, then FOR-USA’s executive secretary, in collaboration with the comic industry’s Benton Resnik. A gift of $5,000 from the Ford Foundation’s Fund for the Republic, a nonprofit advocating for free speech and religious liberty, helped support it.

“We are a pacifist organization, and we believe deeply in the transformative power of nonviolence,” said Ariel Gold, executive director of FOR-USA, based in Stony Point, New York. “And where this comic really fits into that is that we know that nonviolence is more than a catchphrase, and it’s really something that comes out of a deep philosophy of love and an intensive strategy for political change.”

The comic book bears out that philosophy, in part by telling the story of King’s time in Montgomery, Alabama, where he was chosen to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association as Black riders of the city’s buses strove to no longer have to move to let white people sit down. Their nonviolent actions, catalyzed by Rosa Parks’ refusing to give up her seat in 1955, eventually led to a Supreme Court decision that segregated public busing was unconstitutional.

The comic book ends with a breakdown of “how the Montgomery method works,” with tips for how to foster nonviolence that include “decide what special thing you are going to work on” and “see your enemy as a human being … a child of God.”

Ahead of publishing, Hassler received “adulation and a few corrections” from King, to whom he sent a draft, said Andrew Aydin, who wrote his master’s thesis on the comic book and titled it “The Comic Book that Changed the World.” The name of the comic book’s artist, long unknown, was revealed in 2018 to be Sy Barry, known for his artwork in “The Phantom” comic strip, by the blog comicsbeat.com.

Different translations of “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story.” (Images courtesy Fellowship of Reconciliation)

In an edition of FOR’s Fellowship magazine, King wrote in a letter about his appreciation for the comic book: “You have done a marvelous job of grasping the underlying truth and philosophy of the movement.”

The book quickly gained traction. The Jan. 1, 1958, edition of Fellowship noted the organization had received advance orders for 75,000 copies from local FOR groups, the National Council of Churches, and the NAACP. An ad on its back page noted single copies cost 10 cents, and 5,000 could be ordered for $250.

By 2018, the magazine said some 250,000 copies had been distributed, “especially throughout the Deep South.”

The comic book has led to other series in the same genre that also seek to highlight civil rights efforts, using vivid images that synopsize historical accounts of the 1960s. “March,” a popular graphic novel trilogy (2013-2016), was created by U.S. Rep. John Lewis, along with Aydin, his then-congressional staffer, and artist Nate Powell, about Lewis’ work in the Civil Rights Movement. A follow-up volume, “Run,” was published in 2021.

“It was part of learning the way of peace, the way of love, of nonviolence. Reading the Martin Luther King story, that little comic book, set me on the path that I’m on today,” said Lewis, quoted in the online curriculum guide on FOR’s website.

More recently, a new grant-funded webcomic series, “Bad Catholics, Good Trouble,” was inspired by both the King comic book and “March,” said creator Matthew Cressler. Described as a “series about antiracism and struggles for justice across American Catholic history,” it chronicles the stories of Sister Angelica Schultz, a white Catholic nun who sought to improve housing access for African American residents in Chicago, and retired judge Arthur McFarland, who as a teenager worked to desegregate his Catholic high school in Charleston, South Carolina, and later encouraged the hiring of Black staff at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Exceprts from Chapter 2 of “An Exception to the Rule,” a “Bad Catholics, Good Trouble” webcomic story by Matthew J. Cressler, Jennifer Daubenmier, and Judith Daubenmier, illustrated by Marcus Jimenez. (© Cressler, Daubenmier, & Daubenmier)

Cressler said the King comic book’s continued distribution and use in diverse educational settings “make it one of the most significant comics in the history of comics — which is something that might seem wild to say, given how when most people think about comic books, they think of superheroes like Superman or Batman.”

Though different in topic and artistic style, Cressler said, the MLK comic book can be compared to “Maus” by Art Spiegelman and “On Tyranny” by Timothy Snyder — more recent graphic novels about a Jewish Holocaust survivor and threats to democracy, respectively — “as a medium through which to teach, to educate and specifically to politically mobilize.”

Anthony Nicotera, director of advancement for FOR-USA and an assistant professor at Seton Hall University, a Catholic school in South Orange, New Jersey, uses the King comic book in his peace and justice studies classes.

“People are using it in small ways or local ways or maybe even in larger ways,” he said, “and we don’t find out until after it’s happened.”

Gold, a progressive Jew who is the first non-Christian to lead FOR-USA, said future versions are planned beyond the six current languages to further share the message of King, the boycott, and nonviolence. She said this year, her organization is aiming to translate it into French and Hebrew, for use in joint Israeli-Palestinian studies and trainings on nonviolence, as well as for Jewish religious schools.

“Especially in this political moment, I think we really need sources of hope, and we need reminders of the work and the strategy and the sacrifice that is required to successfully meet such an intense moment as this,” she said.