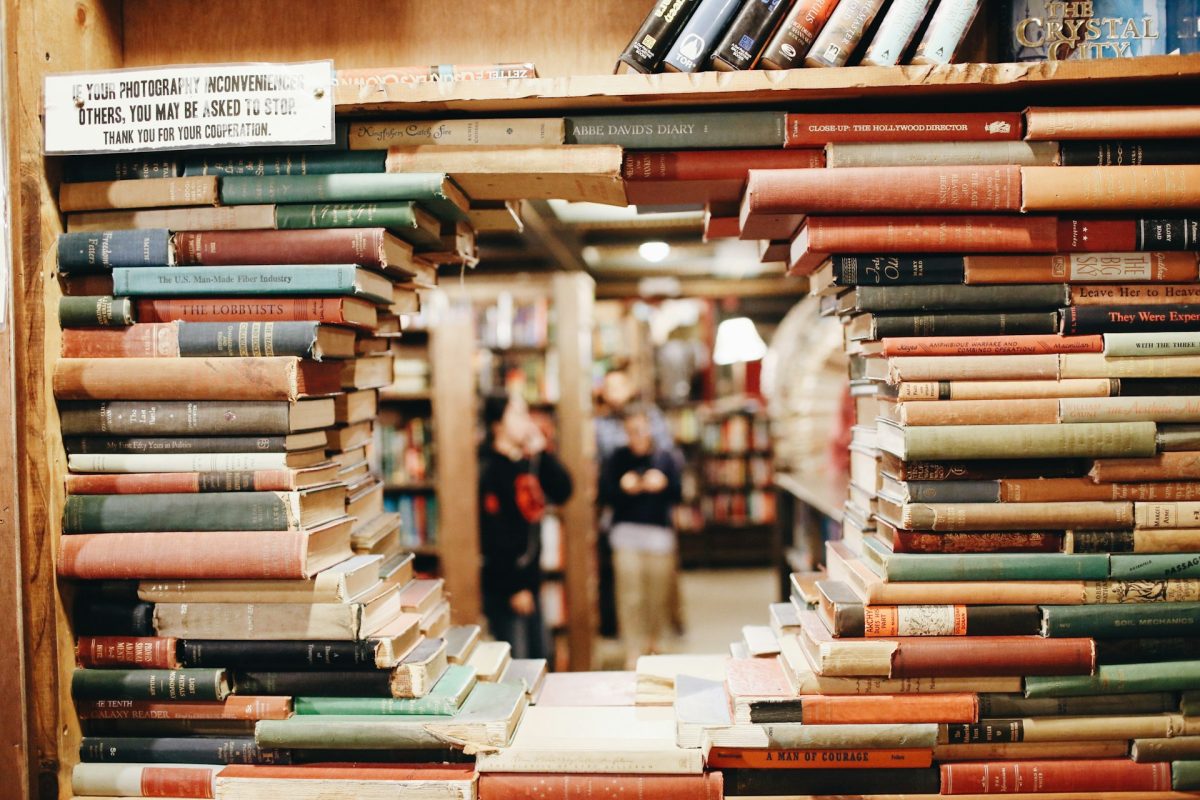

As a preacher, consumer of sermons by other preachers, and teacher of homiletics for over fifteen years, I have noticed a loss in American preaching: preachers are reading less. The reading crisis is an epistemic crisis. Good readers make better writers.

Rodney Kennedy

In my book, Dancing with Metaphors in the Pulpit, I argue that fiction, in the form of short stories or novels, is a bridge to great preaching. After all, the form of the novel is that of the American sermon. Great preaching is the art of larceny — knowing what to steal and from whom — with attribution, of course. If the preacher isn’t a reader, they will not know the new language great readers purloin from other kings whose granaries are filled and whose libraries are famous.

I insisted that my students be readers first, especially readers of Scripture. In this way, they learn Scripture is only rightly read as prayer. My opening lecture each semester of Introduction to Homiletics was an appeal to my preaching students to read. I fully concur with Stanley Hauerwas’s contention: “There is an essential relation between reading and speaking; because it is through reading that we learn how to discipline our speech so that we say no more than needs to be said. I like to think that seminaries might be best understood as schools of rhetoric where, as James suggests, our bodies, and the tongue is flesh, are subject to disciplines necessary for the tongue to approach perfection.”

I assign three books to my students to facilitate their reading lives: The Art of Reading Scripture, edited by Ellen F. Davis and Richard B. Hays; Working with Words: On Learning to Speak Christian by Hauerwas; My Reading Life by novelist Pat Conroy. In addition, I gave each student a bibliography I dubbed, “Two Hundred Books Preachers Must Read.” My students had various reactions to what they considered an assault on their already packed schedules. Students complained they already had too much reading to do in their other classes. Homiletics was supposed to be an easy class as a relief from the complexities of systematic theology and biblical studies.

There are, without question, many lifelong readers among the clergy, but the decline in reading is troubling. When I access sermons on the internet, I hear a lot of pop psychology, warm personal stories, the preacher’s unfolding biography, and quotes from the “wealthy and healthy” genre. I recently watched 100 sermons online and didn’t hear one paragraph of basic Christian theology. There’s plenty of “name it and claim it,” “trust God and be rich,” but not enough Gospel to save the proverbial church mouse.

If the purpose of law school is to teach students to think, the purpose of seminary is to teach students to read. If the people in church are hungry for good news, if they have arrived seeking a word from the Lord, then I believe it is incumbent on the preachers to be prepared with the best possible words to show them the light in the darkness. I can tell if a preacher is a reader by listening to one of their sermons. If the sermon is void of the richness of metaphor, analogy, symbols, myth, and parable, the preacher is not much of a reader. There is a depth to the sermons of those who read that can’t be imitated by those who frantically search the internet for just the right sermon story each week.

This is not a new phenomenon in American preaching. From the frontier days to the 1970’s the saying among seminarians was, “Presbyterians write all the best sermons; the Baptists preach them.” When I first heard that saying, I noticed all of James Stewart’s sermon volumes were in my library. I think I even tried acquiring a Scottish accent for a period of ghastly time.

Martin Marty once observed in an issue of Context that the average rabbi read six times as much as the average Protestant preacher. The reading gap now impacts all of us. It frustrates both the teacher and the preacher in me. My disappointment in the decline of reading goes beyond our entry into the digital age, the oral-video culture. It causes me to feel that my commitments as a scholar and a teacher of reading are threatened. Why? Because I teach and study preaching with the conviction that words matter, that reading is essential, that writing well is paramount, and that the clear articulation of the gospel in both emotional and rational ways should be central to our preaching vocation.

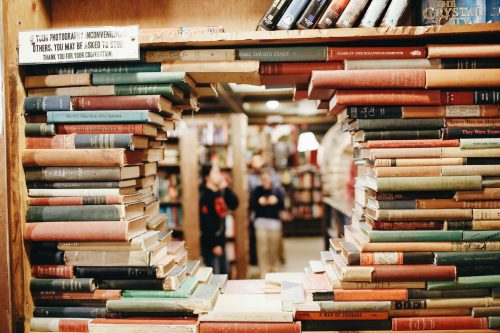

Photo by Fallon Michael on Unsplash

I listened to a sermon in late July by the assistant rector of a local church. After the reading of the lectionary lessons from the Bible, he stood up in a church full of people hungry for good news and gave us a detailed description of his recent vacation, complete with slides. Finally, he said something about how we needed to heed the gospel of Jesus and take some time off for relaxation, said Amen, and asked us to stand and join him in the Nicene Creed. I had never so eagerly awaited the words of the Creed.

Preachers complain of not having time to read. In this scenario, time is a monster devouring the hours of a preacher’s life. The dominant siren of our postmodern, post-truth time is busyness. Some churches feel they can ask the preacher to do everything. Hauerwas argues this experience, common to all preachers, makes us “end up feeling as if [we] have been nibbled to death by ducks.”

Neither AI, the web, the proliferation of available sermons online, the unending lists of “Twenty-five famous quotations,” nor any other instant resource that gets a preacher by on a Saturday evening will suffice for great preaching. As preachers, we are slaves to words. No other word in our language will suffice to describe the suffering, agonizing, and difficult task of stringing together words into phrases, sentences, and making not only sense but enlivening the imagination, rebuking the slothful, encouraging the weary, and lifting up the downtrodden.

The decline of reading has diminished the pulpit. Yet I am heartened when I read a sermon by Kyle Childress or Jim Somerville or Barbara Brown Taylor. There are still many who have not bowed the knee to the god of “busyness” and the idolatry of the instant sermon. These are the men and women who still craft sermons so the preacher can present the word as “some molten words perfected in an oven seven times” (Psalm 12:6).

In a word-cluttered world, it may seem a strange piece of advice — but I still insist to preachers, “Read something.”

Rodney Kennedy has his M.Div. from New Orleans Theological Seminary and his Ph.D. in Rhetoric from Louisiana State University. The pastor of 7 Southern Baptist churches over the course of 20 years, he pastored the First Baptist Church of Dayton, Ohio — which is an American Baptist Church — for 13 years. He is currently professor of homiletics at Palmer Theological Seminary, and interim pastor of Emmanuel Friedens Federated Church, Schenectady, New York. His eighth book, Dancing with Metaphors in the Pulpit, is out now from Cascade Books.