(RNS) — The first two films of Rian Johnson’s Benoit Blanc mystery trilogy, “Knives Out” and “Glass Onion,” are masterfully twisty, broadly comic whodunits populated by tech billionaires, venal politicians, fashionistas, and spoiled old-money family members. The latest, “Wake Up Dead Man,” examines the spiritual battle in contemporary American Christianity as well as one man’s personal struggle with the essence of faith itself.

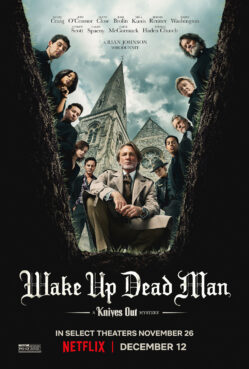

Josh O’Connor, left, and Daniel Craig in “Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery.” Photo courtesy of Netflix

That man, the personality at the movie’s core, is Johnson himself.

Before he was nominated for an Oscar for each of the first two movies in the trilogy, before directing acclaimed episodes of “Breaking Bad” and writing and directing “Star Wars: The Last Jedi,” Johnson was a practicing Christian.

“I was very deeply, personally Christian,” said Johnson, who was raised in churches in Denver before moving to California when he was 11. “My relationship with Christ was the lens I frame the world through, through my childhood, my teenage years, into my early 20s.”

His new film, “Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery,” arriving in theaters Wednesday (Nov. 26) and on Netflix Dec. 12, returns him to that formative terrain with a star-studded cast including Glenn Close, Josh Brolin, Mila Kunis, Jeremy Renner, and Kerry Washington. It is marketed as the charismatic detective’s “most dangerous case yet.”

The story follows a young, welcoming priest, Father Jud (Josh O’Connor), who is sent to assist the violent and morally untoward Monsignor Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin) at Our Lady of Perpetual Fortitude, a fictional Catholic parish in upstate New York. When Wicks is murdered on Good Friday and evidence points to Jud, who has his own violent past, the parish is thrown into chaos, igniting talk of a miracle, a reckoning, and a revolution of the heart.

Blanc, who shows up to solve this “unsolvable” mystery, makes clear he is a sharp and skeptical nonbeliever, but Johnson tapped his Christian past to devise his characteristically complicated story.

“I realized, like a method actor, to write Father Jud, I had to get back to when I was a believer,” Johnson said. “I had to reconnect with the things that I valued, that I drew from. … I mean, that was a tremendously deep experience, that really affected me.”

Today, Johnson describes himself as a nonbeliever. “I don’t know if I classify myself as atheist. I would say I’m just nonreligious. I’m not a Christian anymore,” Johnson said. “Much like Blanc, I can’t say the process ended with conversion back to Christianity for me, but it had a huge effect on me.”

As personal as the subject matter feels, Johnson said he set the film in Catholicism rather than in the Protestant tradition for two important reasons. The churches of his childhood, he said, “all kind of looked like Pottery Barns,” while a Catholic setting felt “exotic,” “a little bit scary” and “awe-inspiring.”

Catholicism also gave him enough distance to explore ideas drawn from his evangelical upbringing without feeling as though he were re-creating it directly. “Putting it in the world of Catholicism gave me a little bit of distance so that I felt like I could speak more directly to it without just hitting it directly on the head,” Johnson said.

Jud arrives at the parish after striking a deacon at his previous posting. A former boxer and outcast, he now attempts to embody mercy and humility. Wicks, an impious, manipulative leader who drives away newcomers with accusatory sermons, clings to control over a shrinking circle of loyal parishioners, all of them suspiciously devoted to Wicks. They include a lawyer, a washed-up novelist, a heartbroken doctor, a former professional cellist who is now paraplegic, and a failed politician turned social-media poster.

“Word’s gotten out every week now it’s just this hardened cyst of regulars, and it seems like you’re intentionally keeping them angry and afraid. Is that how Christ led his flock?” Jud questions Wicks in the first act of the movie.

“Your version of love and forgiveness is a sop,” Wicks responds. “It’s going along to get along with modernity, not wanting to offend this garbage world. Meanwhile, they destroy us, feminist Marxist whores, bit by bit they do, but I carry my burden. I hold the line. And you, you simpering child from Albany. Are you gonna get angry and fight?”

“You’re poisoning this church and I’ll do whatever it takes to save it,” Jud says, concluding the scene.

In Jud, Johnson distilled the spirit of mercy, welcome, and self-giving faith. In Wicks, he captured the fear-driven rhetoric of spiritual warfare and the “us versus them” mentality he remembers from his upbringing.

“They both very much represent sort of a cloud of very real experiences that I had growing up in the church,” Johnson said. “For me, it was therapeutic, in a way, to create both of these characters that represented these aspects of my experience, and then let them come at each other.”

The concept of war, spiritual warfare, fighting against the world and not with it was a common theme, Johnson said, in his churches in Colorado and then Southern California.

“I had, growing up in the church, the side of Jud, which is … Christ-like love, it’s love your enemy,” Johnson said. “On the Wicks side, there was the element of us against them. … We’re under attack. We have to build the walls. We’re at war. This is spiritual warfare.”

Blanc, the self-proclaimed heretic, vows to uncover the truth, but only with Jud’s help. Their encounter becomes more than a narrative device; it serves as a collision point for the two halves of Johnson’s own spiritual outlook.

“I have both of them inside me,” Johnson said. “It’s more of a conceptual thing with Blanc and Jud. Those are literally two poles that are inside me, and letting them have scenes and talk together, that was therapy.”

Blanc reveals his own faith journey: Raised by a very religious mother, he says, “I feel the grandeur, the mystery, intended emotional effect, and it’s like someone has shown a story at me that I do not believe.” Built upon empty promise, “with malevolence and misogyny and homophobia,” Blanc continues, “I want to pick it apart and pop its perfidious bubble of belief and get to a truth I can swallow without choking.”

Jud sympathizes with Blanc’s cynicism but argues that the stories embedded in the church’s structure point to a universal truth. “Guess the question is, do these stories convince us of a lie? Or do they resonate with something deep inside us that’s profoundly true, that we can’t express any other way except storytelling,” Jud said.

“They start their relationship, very much on the fence, and then during the course of the movie, have to form this bond, and this alliance together,” Johnson said. A push-and-pull between faith and skepticism, hope and disenchantment, unfolds between the two, shaping each character’s arc as the film progresses.

“At the end, it was very important to me that they learned something from each other, but they’re still on opposite sides of the fence,” Johnson said. “It’s not like Blanc has a spoiler alert. Blanc doesn’t have a conversion at the end of the movie.”

The movie eventually lays bare the beautiful and troubling parts of Christian faith and leaves room for audience members, no matter their own beliefs, to find honesty and truth in the nuance of solving the unsolvable mystery, which, ultimately, is faith.

Johnson said he did not approach the film with specific hopes for how viewers of faith would respond. Instead, he focused on making something honest to his own experience that let him wrestle with the questions that preoccupy him, and then release it for audiences to engage with on their own terms.

“That’s, to me, the actual purpose of art,” Johnson said. “That’s the purpose of cinema, to put this reactive chemical into the mix and something you never would have expected, and then have people react.”