By Bill Webb

Word&Way EditorCHILLICOTHE — When Norman Shands made a vow to God 65 years ago, he couldn’t have imagined that it would thrust him into the center of the civil rights movement in Atlanta.

The vow — that he would view and treat every person as someone created in the image of God — contradicted the south Georgia native’s upbringing.

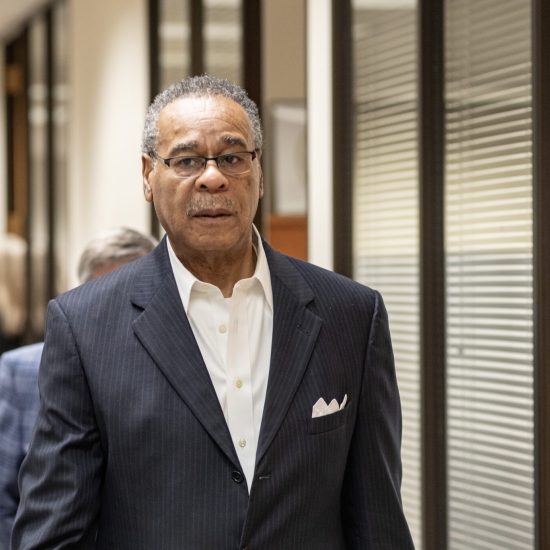

“The process was a work of the grace of God because the only thing that can change prejudice that is ingrained from birth would be the grace of God,” Shands said in a recent interview at the Baptist Home in Chillicothe, Mo., where at 91 he occupies an independent-living apartment and is chaplain to aging Baptists.

The young minister’s concern over the matter culminated a year after graduation from Mercer University, where Shands was the part-time Baptist Student Union director. He was particularly moved during a spiritual focus week when Clarence Jordan of Koinonia Farms in Americus, Ga., told his own story and described his ministry.

Koinonia Farms ministered to the poor and reached across racial lines, and it drew considerable opposition —some of it violent — from people and groups with a racist bent.

Shands was deeply moved by what he heard from Jordan.

“I made a vow in private prayer with God that with God’s help I would spend the rest of my life, to the best of my ability and knowledge, treating every person, regardless of race or sex or class or whatever, as a person made in the image of God,” he recalled.

Following short stints as director of religious activities at Mercer and president of Limestone College in Gaffney, S.C., and five years as pastor of First Baptist Church, Spartanburg, S.C., Shands was called in 1953 as pastor of West End Baptist Church in Atlanta.

Like much of the South, Atlanta was being forced to deal with the race issue. Shands didn’t go out of his way to address it at first, but he didn’t shy away from it in his preaching and teaching either.

That all changed during the Georgia Baptist Convention annual meeting in the fall of 1956. Shands was a member of the convention’s four-man Social Service Commission, which brought a controversial report to messengers.

The report addressed the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954 and the court’s order in 1955 to desegregate public schools. The commission called for Georgia Baptists to obey the court order and serve as agents to help make the transition to integration of the schools a peaceful one. It called for Christians and churches to proclaim that God intended the gospel for every person.

The convention rejected the report by a 3-1 margin after one of the four commission members brought a minority report and “Mr. Baptist” —Atlanta pastor Louie B. Newton — spoke against it.

Shands’ picture and a quote appeared in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution’s convention report the next day. The pastor’s stand and the resulting notoriety caused a stir among West End’s deacons and other members.

Deacon chairman John Still visited Shands at home a few days later and asked how he should reply to other deacons who ask him what he thought about Shands and his stand on integration.

Shands responded, ‘Well, what have you been saying to them?’”

“I’ve been saying I don’t agree with him, but he’s my pastor, and I’m loyal to him as my pastor,” Still said.

At Shands’ suggestion, Still called a meeting to allow the deacons and their pastor to discuss the concerns.

“We had a meeting that wasn’t too harmonious,” Shands recalled with a smile. A former deacon chairman made a motion that they go on record before the congregation censuring the position their pastor had taken at the convention.

Tension in the room was high when Still told of his own preparation for the special called meeting. Describing himself as a Southerner in every way, Still said he had taken three days off work to study.

He picked up his Bible and read two passages he had taught the boys in his Sunday school class. Shands vividly remembers what he said next: “Both of these passages say I’m not in accordance with the Scripture, so I want to resign my position as chairman of deacons.”

Amid calls of “no, no, you don’t need to resign,” Still broke down, turned the meeting over to someone else and went to another room. After Still composed himself and returned to the meeting, he had one more thing to say: “Now, you need to know that if you’re going to throw any rocks at this man, you throw them at me. I am going to be between you and him.”

Shands’ eyes reddened as he recalled the event and noted that Still’s stand defused the anger and likely kept him from being dismissed. The motion to censure was tabled.

The pastor discovered that while his stand at the convention brought opposition, it also drew interest and support from people who shared his concerns about human dignity and peaceful integration in Atlanta.

Shands encouraged dialogue and participated in meetings involving ministers and other leaders of various faith groups, and he participated in ongoing meetings between local white and black pastors, including one who would become a good friend, Martin Luther King Sr., pastor of Ebeneezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and the father of the martyred civil rights leader.

Shands became one of the original 80 signers of the Atlanta Ministers Manifesto, a full-page ad published in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution in late 1957. It affirmed freedom of speech, obeying the law, preserving public education, eradication of hatred between races, communication and the importance of prayer.

The Interdenominational Ministers Alliance of Atlanta, representing virtually every black church in Atlanta, issued a favorable response. The next year, 315 ministered signed a revised version of the Mani-festo.

Shands completed 10 years at West End Baptist Church and was called in 1963 as pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Kansas City, where he continued efforts at dialogue to help improve the racial climate. Later he returned to Southern Seminary, where he held various positions before retiring in 1980.

Shands doesn’t talk much about the intimidation he and his family experienced while in Atlanta. His son, Bob, recalls that when cars would slow or stop in front of their house, lights would be turned off, the children would be ordered away from the windows and told to crouch on the floor.

The Ku Klux Klan and other groups were active, and there was good reason to fear violence.

Hateful anonymous calls came to the house frequently. Very often, Shands’ wife, Catherine, answered them.

“I never felt that I was doing anything but preaching the gospel and standing for what Christ stood for with the universality of His invitation and affirming human dignity. That’s the way I feel about it today,” Shands maintains.

“To see changes in Christians who dared to go against the current have been satisfying to me, too.”

Bob Shands wrote a book in 2006 titled, In My Father’s House: Lessons Learned in the Home of a Civil Rights Pioneer. It chronicles his father’s contributions bridging racial barriers and the impact those times had on him as a youngster.