WASHINGTON (RNS)—When seventh-grader Raymond Hosier was suspended for wearing rosary beads to school in May, civil rights groups rushed to his defense.

“Without question, the continuing action taken by the school district in punishing Raymond for wearing a rosary to school violates the constitutional rights of our client,” argued Jay Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice.

After Sekulow filed a lawsuit, a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order June 1, telling Oneida Middle School and the school district in Schenectady, N.Y., to allow Hosier, 13, to wear the rosary to class.

Like school principals and superintendents in other states, including Texas, California, Oregon and Virginia, Oneida officials say the no-rosary-beads rule is necessary to “protect students from violence and gangs.”

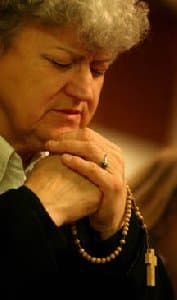

Maria Kobal of Euclid, Ohio, prays the rosary at the Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes in Euclid, Ohio. Law enforcement officials around the country say gangs have adopted the rosary as a symbol that is protected by the First Amendment. (RNS FILE PHOTO/Chris Stephens/The Plain Dealer of Cleveland)

|

They have a point, according to gang experts. After schools began banning gang-related bandanas, clothing and hairstyles about a decade ago, students have turned to rosaries as a subtle and often First-Amendment-protected way to signal gang allegiance.

“With the introduction of strict dress codes and the use of uniforms in the school systems, these type of indicators seem to be favored by the gangsters,” the San Antonio Police Department says in a handbook about gang awareness.

Gangsters not only wear certain colors—reds for Bloods, blues for Crips, for example—they also arrange the beads to signal their rank in the gang, and they teach young members to plead religious freedom if they’re hauled into the principal’s office, said Jared Lewis, a former police officer in California who worked in public schools.

“You are often dealing with gang members who have no inkling or cares about the religious significance of the rosary beads,” said Lewis, who now runs Know Gangs, a training group for law enforcement officials. “They are just trying to skirt around school rules under the guise of a religious symbol.”

No one is sure which gang started the trend of wearing rosaries, said Robert Walker, a former head of the gang-identification unit for the South Carolina Department of Corrections. Like a lot of gang fads, he said, it likely started in California and migrated east.

“One gang started it. Who it was, nobody knows. Another gang saw it and thought it was cool, and started using it, too,” Walker said. “These things just evolve.”

In Roman Catholic parlance, the Rosary refers to a sequence of prayers and meditations on the life of Jesus, although the word often is used outside the church to refer to the circlet of beads, as well.

Each of the beads, usually 55 or 155, represents a prayer—a Hail Mary, Our Father or Glory Be—and is grouped in sets of 10 with a crucifix hanging from a pendant. The beads help mark which prayers have been recited and guide the supplicant through the life of Jesus.

Rosaries fell out of favor among Protestants because the Roman Catholic Church used them to promote indulgences—papal dispensation from time in purgatory. After the Reformation, the beads became a defiant emblem for Catholic monks and nuns to wear outside their habits and a tactile tool for missionaries to pass on the faith—particularly in Latin America.

Now, Latino gangsters are the most frequent—and creative—wearers of rosaries, said Lewis. The Latin Kings, for example, use colors to signal members’ rank in the hierarchy—five black and five gold beads for members; two gold beads for top dogs. Assassins wear all black.

The Netas, an East Coast gang founded in Puerto Rico, wear 78 red, white and blue beads to symbolize the 78 towns in Puerto Rico.

Prospective members wear all white beads until they join the gang.

Lewis noted he sympathizes with principals who are torn between respecting religious rights and preventing gang wars in their schools.

“We live in a country where, obviously, people should be able to do and say what they want,” he said. “At the same time, if something happens on school grounds, the school principal is going to be held liable for not keeping students safe.”