FLOWER MOUND, Texas — Fraud prevention beats fraud detection—especially for churches, Verne Hargrave, a certified public accountant and fraud examiner, told a group at RockPointe Church in Flower Mound, Texas.

“The reason why we try to do fraud prevention rather than fraud detection is because it is very hard on your stomach to get into fraud detection,” Hargrave said at the seminar, sponsored by Denton Baptist Association. “No. 1, you worry you didn’t catch it all, and then you’re overwhelmed with the sadness of it when it happens in the church.

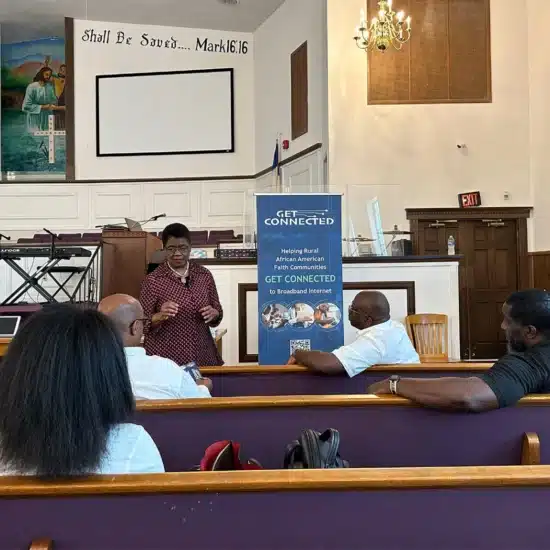

Verne Hargrave (left), a certified public accountant and fraud examiner, discusses fraud prevention in churches with Denton Baptist Association Director of Missions Gary Loudermilk. (PHOTO/George Henson)

|

“A business, they dust themselves off, and then they move on. With churches, unfortunately, the money loss often isn’t the worst part of the loss. It’s the aftermath—the tsunami of bad feelings and the loss of trust.”

After experiencing that turmoil in a church whose pastor was found to be inappropriately using funds—“half the church wanted to forgive him, and the other half wanted to execute him on the spot”—Hargrave decided he would rather stop it before it happened.

The recent economic downturn has led many churches to cut expenses by trimming staff and benefits, and some have stopped administrative procedures like outside audits. All of those things heighten the risk of fraud at the worst of times.

“History shows that’s not really the time to be cutting back (on auditing expenses), because there is a spike of fraudulent activity during downturns,” Hargrave said.

Fraud is built on three elements—economic pressure, rationalization and opportunity, he said.

“It’s not usually crooks who seek out churches to steal from. It’s usually good people who find themselves in bad situations which causes them to even contemplate doing something they know is wrong,” he said.

Medical bills, personal debt or unforeseen expenses can put pressure on people to find cash from sources they normally wouldn’t consider.

Rationalization is what these good people tell themselves to convince them it is all right to take the money. The chief rationalization of those who defraud churches is: “I wasn’t stealing it; I was going to pay it back,” Hargrave said.

“But in addition to economic pressure and rationalization, there has to be a way for the fraudster to get into your system and take the money and not get caught,” he continued.

“You have very little control over the pressure and the rationalization. That’s almost totally out of your control, but you have total control over the opportunity. If the opportunity is shut down, then the pressure will be there. But the rationalization, it will be very difficult for them to cross that hurdle, because they know they’re probably going to get caught,” Hargrave said.

While most churches think it’s not a problem they need to worry about, that’s not true, he said. Four to 5 percent of all reported fraud is in churches.

“I would submit to you that it’s probably a larger percentage than that, because we as religious organizations have a tendency to sweep that under the rug, because we don’t want it to get out,” he speculated.

The median loss for churches in fraud cases is about $105,000.

“So, every time one of these losses takes place, it’s probably going to be in that six-figure ballpark, which in most churches, that’s going to hurt something. Something is going to have to be cut, so it can be significant,” Hargrave pointed out.

Some churches may believe they don’t have enough money to worry about it.

“You are a lucrative target, whether you believe it or not. You have the one thing thieves want, and that’s money. They don’t have to take something out and sell it or anything like that,” he said.

Having a lot of designated accounts where money can sit for years before it is spent can make churches prime targets because it may take awhile for anyone to notice the money is missing, Hargrave added.

“Most people still operate under the illusion that it can’t happen here. That’s the hardest hurdle we have to get over,” he said. “You have an environment conducive to that kind of activity—we trust and forgive rather than trust and verify.”

Churches can guard against fraud through policies and procedures followed strictly, he said.

“You need to have policies and procedures that are well-documented, that are adhered to and reviewed periodically. In 25 pages or less, you can have a very concise policy, but you need to do that,” Hargrave said.

A chief part of those policies and procedures should be a segregation of the financial duties. For example, the person who inputs deposits should not be the same person who writes all the checks and then later balances the bank statement. The greater number of eyes on the numbers, the less anyone will take a chance of being discovered doing something they shouldn’t.

“These procedures are not primarily to protect money, but to protect staff from false accusations and the reputation of the church. Money can sometimes be replaced somewhat quickly, but reputations are hard to recover,” he said.