JEFFERSON CITY – Imagine for a moment that you are an 18-year-old college freshman and the first semester will end in a few weeks. Where will you stay until classes resume in January?

Or imagine you are 18 and have just graduated from high school. You need a job, a place to stay, transportation and life direction. Who do you rely upon for support?

Most students could respond, "Mom and dad or my family would help me." But youth in the foster care system in Missouri often don't have an answer for either question or the host of others they face as they age-out or are "emancipated" from state control. Many don't have a trusted adult from whom they can even seek advice.

Thanks to Transitions, a new program developed by the Jefferson City-based Central Missouri Foster Care & Adoption Association, 10 area students are getting help to make the move from ward-of-the-state to productive citizen.

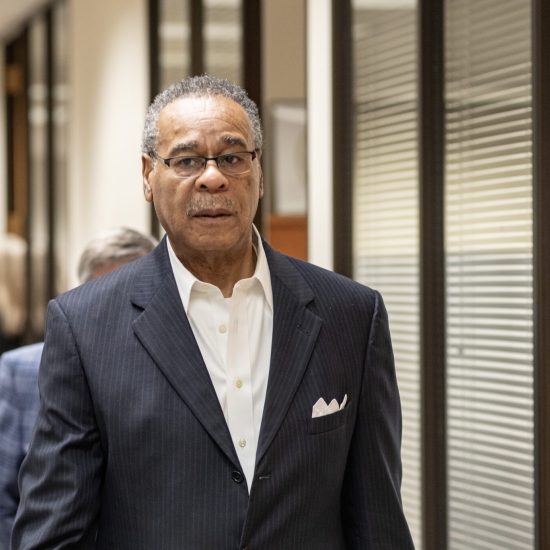

Transition graduates for 2011. Program leaders include Felicia Toran, Sara Mengwasser, Patricia Andrews, Mandi Billingsley, DeAnna Alonso (Central Missouri Foster Care & Adoption Association executive director), Casey Littrell, BriAnna Boney, Stacey Nunnelly, Mindy Ulstad (CMFCAA Board president).

|

Why do older foster youth need help? According to several national studies, foster children aging out of the system are more likely to be unemployed, to become homeless, to need public assistance or to become a single parent. Many also end up in legal trouble or become incarcerated. Some studies suggest that as many as half are homeless within the first 18 months of release from state care.

Less than a third complete high school or earn a GED, and foster youth are much less likely to earn a college degree.

Association Executive Director DeAnna Alonso knows from personal experience the difficulty older youth in the system face. An emancipated foster child, she developed and has been the driving force behind the Transitions program. "She is the heart and soul of Transitions," noted Amanda Towns, interim director until Alonso returns from medical leave.

Transitions, just completing its first year, focuses on mentoring as a primary way to make a difference in a student's life. The not-for-profit association received a Walmart grant in 2010 to fund the service for two years.

The program targets students entering their senior year in high school, matching each youth with an adult having similar interests or expertise. When Tisha Spencer, a member at Memorial Baptist Church in Jefferson City and an association board member, heard about Sara Mengwasser, she leaped at the chance to be a mentor.

"When the Transitions program was formed last year, the executive director told us of a senior girl who was very interested in cars and [who was] part of the auto tech program at Nichols Career Center," Spencer explained. "When I was a teenager, I was very interested in cars myself and restored a 1967 Camaro from the frame up with help from my family.

"When I heard about Sara, I knew immediately God was calling me to get involved."

Spencer's participation sparked another calling – to recruit more mentors. "Our number one need is to find mentors…and it's been my goal to find Christian mentors," she said.

Mentors are asked to commit to a student for two years, contacting him or her at least once each month throughout the first year.

During the student's senior year, the mentor acts as a sounding board to help the student determine whether to attend college or trade school and to fill out necessary forms and applications. Missouri provides funding for higher education until the student reaches age 21.

Mentors working with youth who opt to find a job offer advice about living on one's own and finding services for which the young adult might qualify.

All make sure their student attends required meetings and classes – including courses on budgeting, healthcare and interviewing.

Students also are required to complete at least 15 hours of community service the first year.

Seven student participants graduated from high school in May. Two are already living on their own, and several others are headed to college or trade school. One student has received a music scholarship. Sara, now a certified auto technician, will attend Lincoln University in Jefferson City to earn a business degree. She plans to open her own auto shop one day.

Stacey Nunnelly, the young woman Stephanie Martin mentors, will begin cosmetology school. Adopted by her foster mom, Stacey no longer qualifies for state aid. But with seven other children in the home, she has been able to rely on Stephanie to walk with her through some decisions.

Two years may sound like a long commitment to someone considering the program. "But if you get a good match, it doesn't turn into an obligation," Martin said.

Her satisfaction comes from watching her student's growth. "She's just part of our family now…. It's watching her grow that makes me happy," Martin said. "The satisfaction comes from watching her succeed."

Spencer agrees. "Sara is a great kid. If I can be a part of helping her and of seeing her make a success of her life, that's a blessing to me."

With the grant, Transitions is able to provide the extras for the high school prom and graduation, including senior photos, and a laptop computer. But the program hinges on its mentoring aspect.

"Mentors are so valuable. They are almost like a go-between," Towns explained. "Foster parents are wonderful, but they are so busy. Mentors are a partner with the families."

"Even if we don't find enough money for the laptop or the prom events…if we can just match more students with mentors, that would be great," Spencer added.

Vicki Brown is Associate Editor of Word&Way.