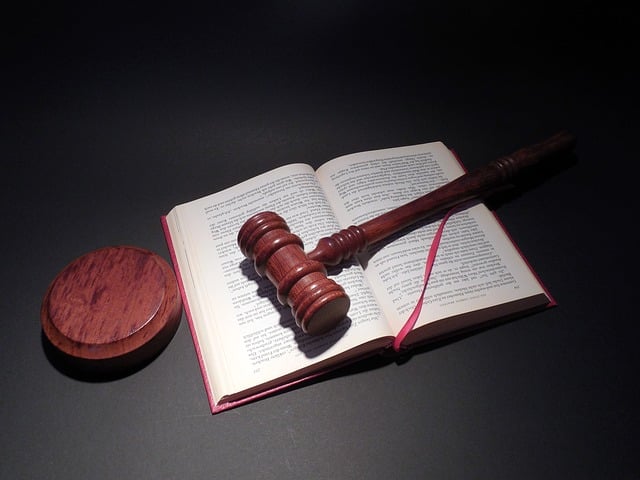

In the Missouri Baptist Convention’s nearly 16-year legal battle against five Baptist ministries, the remaining two cases are now before the Missouri Court of Appeals, Western District. Cole County Circuit Court Judge Karl DeMarce ruled Sept. 27 for the MBC in its cases against Missouri Baptist University and The Baptist Home. Both MBU and TBH filed notices of appeal shortly after that verdict. They then filed longer briefs on May 2 in hopes of persuading the appellate judges to overturn the lower court’s ruling. The MBC has until July 2 to file its response.

PixabayThe MBC first filed suit against the Missouri Baptist Foundation, MBU, TBH, Windermere Baptist Conference Center and Word&Way in 2002 following moves by the five boards to shift to self-perpetuating status in 2000 and 2001. The MBC lost multiple suits against Windermere Baptist Conference Center, dropped its claims in a nearly-identical case against Word&Way and saw the estate of businessman William Jester win a settlement in a countersuit against the MBC. The MBC won its case against — and control of — the Missouri Baptist Foundation.

PixabayThe MBC first filed suit against the Missouri Baptist Foundation, MBU, TBH, Windermere Baptist Conference Center and Word&Way in 2002 following moves by the five boards to shift to self-perpetuating status in 2000 and 2001. The MBC lost multiple suits against Windermere Baptist Conference Center, dropped its claims in a nearly-identical case against Word&Way and saw the estate of businessman William Jester win a settlement in a countersuit against the MBC. The MBC won its case against — and control of — the Missouri Baptist Foundation.

TBH’S Arguments

TBH argues in its appeals brief, as does MBU, that the MBC lacks standing to bring the case since the MBC is not a member or director of the separate organization or the state’s Attorney General — as required in the relevant nonprofit statute.

A key issue for both institutions, but especially in TBH’s brief, is that they were created as Chapter 355 nonprofits (like Windermere and Word&Way) rather than as Chapter 352 nonprofits (like the Foundation). The differences between those two parts in Missouri state law include the process involved to change a nonprofit’s charter. Thus, TBH argues the standing ruling in the Foundation case is “irrelevant” and “inapplicable.”

TBH notes that the key provisions in Chapter 355 that the MBC bases its arguments on did not even exist — and thus should not be considered binding — when TBH adopted its 1960 charter that it changed in 2000. Thus, TBH claims the passage in the 1960 charter granting rights of approval or rejection to the MBC were “void ab initio [from the beginning] as a matter of law.” TBH insists the MBC “never had any valid right to approve or reject the 2000 amendments” and the circuit court was “instead engaging in unauthorized statutory construction.”

TBH also argued the DeMarce erred not only in his original judgment but also by denying TBH’s motion on Oct. 27 to amend, correct or modify the order due to his inclusion of “two relevant findings of fact that are plainly inaccurate and without support in the record.” First, TBH contends that despite DeMarce’s claim, the MBC did not disapprove “in writing” of TBH’s charter amendments in 2000. Second, TBH insists he mistakenly claimed TBH’s charter and the MBC’s Constitution required MBC approval for the creation of The Baptist Home Foundation.

MBU’S Arguments

MBU contends in its appeals brief that the key first event was not its trustees’ vote to move to a self-perpetuating board, but rather that the MBC “significantly changed the procedures and rules for appointing individuals to” the board. In 2001, more conservative leaders crafted new guidelines that would disqualify many MBU trustees from additional terms. MBU “contends those changes were improper and harmed the University,” thus leading the self-perpetuating vote by the trustees.

In addition to refuting claims by the MBC, MBU also levels several claims against the MBC, “including breach of fiduciary duty, unclean hands, breach of good faith and fair dealing and breach of the 1997 Charter by the Convention.” MBU argues “the trial court erred” in ruling for the MBC since the MBC had not negated these affirmative defenses.

Many of those claims are largely based on the new nominating committee rules in 2001 that MBU insists violated the MBC’s “Nominating Committee Rules and Procedures,” the MBC’s Constitution and Bylaws and MBU’s 1997 charter (the last charter before the self-perpetuating vote in 2001). MBU also argues the new nominating rules would have had negative impacts on MBU’s management, fundraising and accreditation. Thus, MBU claims, its trustees acted within their fiduciary responsibility to move to a self-perpetuating board.

MBU also highlights admissions by the MBC in a previous lawsuit involving an accident at Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Mo., another MBC-affiliated college with a similar relationship to the MBC as that which MBU had before the charter change. MBU notes that “the Convention unequivocally represented to the court that if Southwest Baptist amended its charter without Convention approval, the Convention’s only remedy was to halt donations to the institution from the Convention’s ‘Cooperative Program.’” The MBC now claims institutions cannot change their charters at all without the Convention’s approval.

“The Convention has not owned or operated the University; and does not hold title to the University’s real or personal property,” MBU’s brief notes. “Neither the Convention, nor its Executive Board, has donated their own money to the University.”

Additionally, MBU argued “the trial court erred” when DeMarce claimed he could not consider MBU’s affirmative defenses without engaging in “ecclesiastic disputes.” MBU insists “those defenses could be decided on neutral principles of law, did not require deciding or weighing religious or ministerial issues, and the defenses were based upon corporate governance documents, corporate procedural statutes, inequitable non-religious conduct and did not arise from religious disputes or religious principles.”

Brian Kaylor is editor and president of Word&Way.