The Slave Bible exhibit at the Museum of the Bible features a version of the holy book that excluded major portions of the Old and New Testaments. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksWASHINGTON (RNS) — On display on the ground floor of the Museum of the Bible there is a lone volume that stands out from the many versions shown in the building devoted to the holy book.

The Slave Bible exhibit at the Museum of the Bible features a version of the holy book that excluded major portions of the Old and New Testaments. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksWASHINGTON (RNS) — On display on the ground floor of the Museum of the Bible there is a lone volume that stands out from the many versions shown in the building devoted to the holy book.

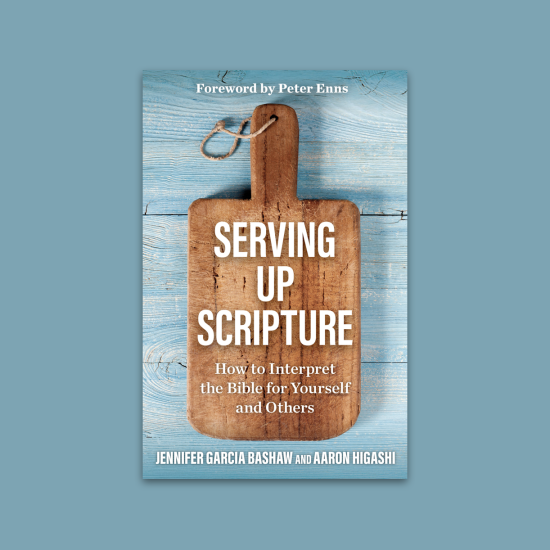

It’s a small set of Scriptures whose title page reads “Parts of the Holy Bible, selected for the use of the Negro Slaves, in the British West-India Islands.”

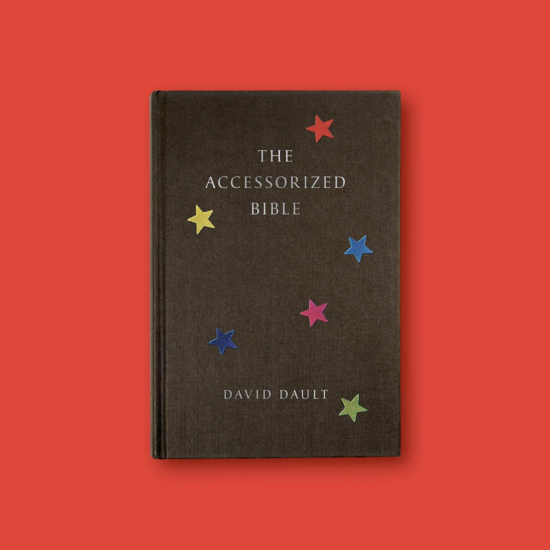

The so-called Slave Bible, on loan from Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., excludes 90 percent of the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, and 50 percent of the New. Its pages include “Servants be obedient to them that are your masters,” from Paul’s letter to the Ephesians, but missing is the portion of his letter to the Galatians that reads, “There is neither bond nor free … for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”

The Slave Bible exhibit at the Museum of the Bible features a version of the holy book specifically printed for converting slaves to Christianity. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksSince opening more than a year ago, the museum has featured this 15-inch-by-11-inch-by-4-inch volume in an area that chronicles Bible-based arguments for and against slavery dating back to the beginnings of the abolition movement.

The Slave Bible exhibit at the Museum of the Bible features a version of the holy book specifically printed for converting slaves to Christianity. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksSince opening more than a year ago, the museum has featured this 15-inch-by-11-inch-by-4-inch volume in an area that chronicles Bible-based arguments for and against slavery dating back to the beginnings of the abolition movement.

But in anticipation of next year’s 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first African slaves in the New World, in Jamestown, Va., the Slave Bible will be on special view until April in an exhibition developed with scholars from Fisk and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“We feel it’s an opportunity to contribute to important discussion today about the Bible’s role in relationship to human enslavement and we know that that connects to contemporary issues like racism as well as human bondage,” Seth Pollinger, director of museum curatorial, told Religion News Service.

“We’ve had such visitor interest in this book, probably wider interest in this single artifact than any other artifact in the museum.”

The rare artifact is just one of three known across the world. The other two are housed at universities in Great Britain.

Fisk’s scholars believe its version may have been brought back from England in the late 19th century by the school’s famed Jubilee Singers, who sang spirituals to Queen Victoria during their European tour.

The exhibition draws on the dichotomy of coercion and conversion, keeping slaves in their place while also attempting to tend to their souls. On two walls portions of the Bible that were excluded from the slaves’ text are juxtaposed with verses determined to be appropriate for them.

“Prepare a short form of public prayers for them … together with select portions of Scripture … particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters,” said Anglican Bishop of London Beilby Porteus, founder of the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves, in 1808.

Anthony Schmidt, curator of Bible and religion in America for the Museum of the Bible, said that quote “kind of shatters our ideas of these abolitionists being so progressive. Porteus held to very racist views even as he fought for the freedom of enslaved Africans in these colonies.”

A London publishing house first published the Slave Bible in 1807 on behalf of Porteus’ society.

Absent from that Bible were all of the Psalms, which express hopes for God’s delivery from oppression, and the entire Book of Revelation.

“That’s where you really have the story of the overcomer, and where God makes all things right and retribution,” Pollinger said of the final book found in traditional versions of the Christian Bible.

The Slave Bible’s Book of Exodus excludes the story of the rescue of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, the liberation that gives the biblical book its title.

“It’s conspicuous that they have Chapter 19 and 20 in there, which is where you got God’s appearance at Mount Sinai and he gives his law,” said Pollinger. “The Ten Commandments would be Exodus 20 but missing is all of the exodus from Egypt.”

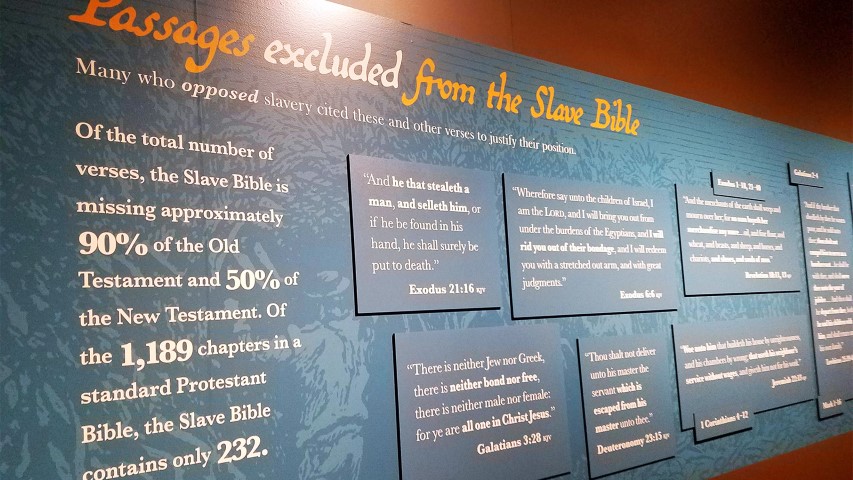

Holly Hamby of Fisk University. Photo by Vando Rogers/Fisk University PhotographerScholars acknowledge that the little-known Bible can be a shocking discovery for students and museum visitors alike.

Holly Hamby of Fisk University. Photo by Vando Rogers/Fisk University PhotographerScholars acknowledge that the little-known Bible can be a shocking discovery for students and museum visitors alike.

“When they first encounter the Slave Bible, it’s pretty emotional for them,” said Holly Hamby, an associate professor at Fisk who uses the artifact as she teaches a class on the Bible as literature. Many of the students at the historically black university are Christian and African-American, most of whom are descendants of slaves, including those in the West Indian colonies.

“It’s very disruptive to their belief system,” said Hamby, who is currently teaching from a digitized version of the Slave Bible.

Some students wonder how they could have come to the Christian faith with this kind of Bible possibly in their past. Others dive deeper into the complete Bible, including the Exodus story.

“It does lead them to question a lot but I also think it leads them to a powerful connection with the text,” she said. “Very naturally, seeing the parts that were left out of the Bible that was given to a lot of their ancestors makes them concentrate more on those parts.”

The museum has plans for conferences and panel discussions to further explore the unusual artifact and its complex meanings.

Pollinger hopes it will offer a chance for a more diverse range of visitors, black and white, to join in discussions, just as white and black scholars have worked in recent months on the exhibit.

“This exhibit is going to destabilize people; it’s going to disturb people and it’s not necessarily one group rather than the other,” said Pollinger, who hopes that learning about this piece of Bible history will foster greater understanding.

Seth Pollinger, director of museum curatorial, at the Slave Bible exhibit. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksIn a quotation displayed in the exhibit, Brad Braxton, director of the NMAAHC’s Center for the Study of African American Religious Life, says: “This religious relic compels us to grapple with a timeless question: In our interpretations of the Bible, is the end result domination or liberation?”

Seth Pollinger, director of museum curatorial, at the Slave Bible exhibit. RNS photo by Adelle M. BanksIn a quotation displayed in the exhibit, Brad Braxton, director of the NMAAHC’s Center for the Study of African American Religious Life, says: “This religious relic compels us to grapple with a timeless question: In our interpretations of the Bible, is the end result domination or liberation?”

Hamby suggested that the exhibit should feature current Fisk students’ voices, so it includes a video of them discussing questions surrounding the controversial take on the Bible.

“My favorite question is the last question on the list that we asked them, which is: Do you think that this Bible is still the good book?” she said of questions the students were asked and the public will have an opportunity to answer for themselves.

For her part, Hamby, a United Methodist, says: “It’s a good book. I still believe in the Bible on the whole but not this version of it.”<