Around significant anniversaries, churches will often produce a write-up of their history. Sometimes it will be a book, other times just a page for the anniversary program or the church’s website. Throughout the biblical narratives, people placed monuments to mark key moments and help them remember their past. But what if we’ve left out some important details? Does your church need to reconsider the ugly parts of our history we may have left out?

Brian Kaylor

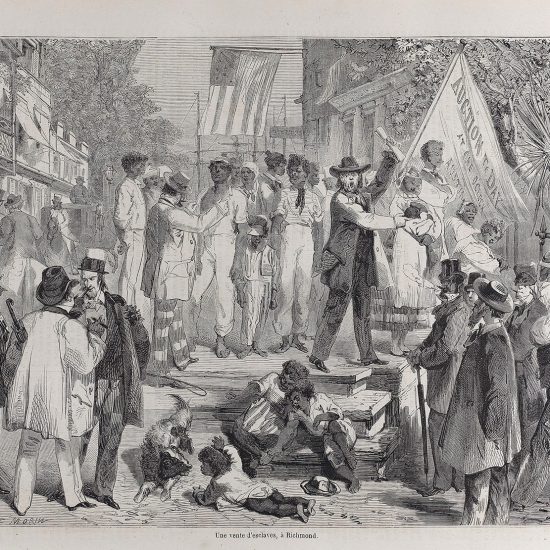

August 20 (Tuesday) marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in what is now the United States. To mark the occasion, churches in several states held services to reflect on that legacy. Some of these services emerged out of the Angela Project, a three-year collaborative project of the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, National Baptist Convention of America, and Progressive National Baptist Convention that is named for one of the first enslaved persons to arrive in 1619.

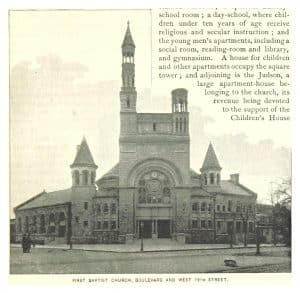

First Baptist Church in Jefferson City, Mo., hosted one of the Angela Project prayer services. The interracial, ecumenical community service included part of a litany created for the occasion by Simmons College of Kentucky, a black Baptist school in Louisville. Clergy from FBC, Second Baptist Church (a black Baptist church started in 1863 by enslaved members of FBC), a Catholic congregation, and an African Methodist Episcopal congregation participated.

My role in the service was to report on the ties between early FBC leaders and slavery, including many details that had not been told before. To prepare, I examined the census data to determine if any of our pastors or other key leaders had been slaveholders. While the church’s history notes the fact there were enslaved members that eventually left to create Second Baptist, any details about who held others in bondage had not been included.

“If we’re not willing to speak honestly about the past, why would we expect people to trust us to speak truthfully in the present or future?” Church history image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

So, we told some uncomfortable truths about our own congregation. It turns out that four of the first seven pastors held people in slavery. And three of those seven pastors served in the Confederacy. Eight of the eleven white charter members were slaveholders, including a future mayor of Jefferson City and a future present of William Jewell College in Liberty, Mo. And the man who donated the land where the church now sits held several people in slavery. We passed out a more detailed account, which FBC also posted online. And the local newspaper’s report on the Angela Project service focused on the historical admissions.

We may not want to admit such details. But we should not pretend it’s not true. Ignorance might be bliss, but it doesn’t help us make progress. As Jesus taught, “the truth will set you free.”

I recognize some may not believe it’s helpful to dig into the ugly parts of our past or to air our dirty laundry in public. However, I see such work as an important first step in working on racial justice and creating what Martin Luther King Jr. called the beloved community. If we’re not willing to speak honestly about the past, why would we expect people to trust us to speak truthfully in the present or future? And in an age of doublespeak and political expediency, a church that is willing to be transparent could attract the attention of a world craving authenticity.

So, how’s your church’s history? Does it whitewash the past or look honestly at it? Especially for those churches established before 1865, it can be important to research the possible slaveholders among early pastors, charter members, and other key leaders. But even churches created a few decades after the emancipation of the enslaved persons might find a few older pastors or leaders had previously enslaved people before the Civil War.

Let’s do the holy work of research so that we can move to the next steps of confessing, lamenting, repenting, and repairing. Let’s speak honestly here in the present about the past so that we can build a better future.

Brian Kaylor is editor and president of Word&Way.