Former Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch is sworn in to testify before the House Intelligence Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, Friday, Nov. 15, 2019, during the second public impeachment hearing of President Donald Trump’s efforts to tie U.S. aid for Ukraine to investigations of his political opponents. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon, Pool)

(RNS) — As the impeachment hearings proceed on Capitol Hill, it’s astonishing to follow the reactions to the developments on social media, where the constant stream of tweets, likes, comments and shares is apparently further polarizing the American electorate.

Watching this action, I began to question how the social media torrent is affecting people of faith.

To get a sense of this, I took a look at a battery of five questions from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study, which was put into the field in the fall of 2018. It asked respondents if they have done any of the following on social media:

-

- 1. Posted a story, photo, video or link about politics

- 2. Posted a comment about politics

- 3. Read a story or watched a video about politics

- 4. Followed a political event

- 5. Forwarded a story, photo, video or link about politics to friends

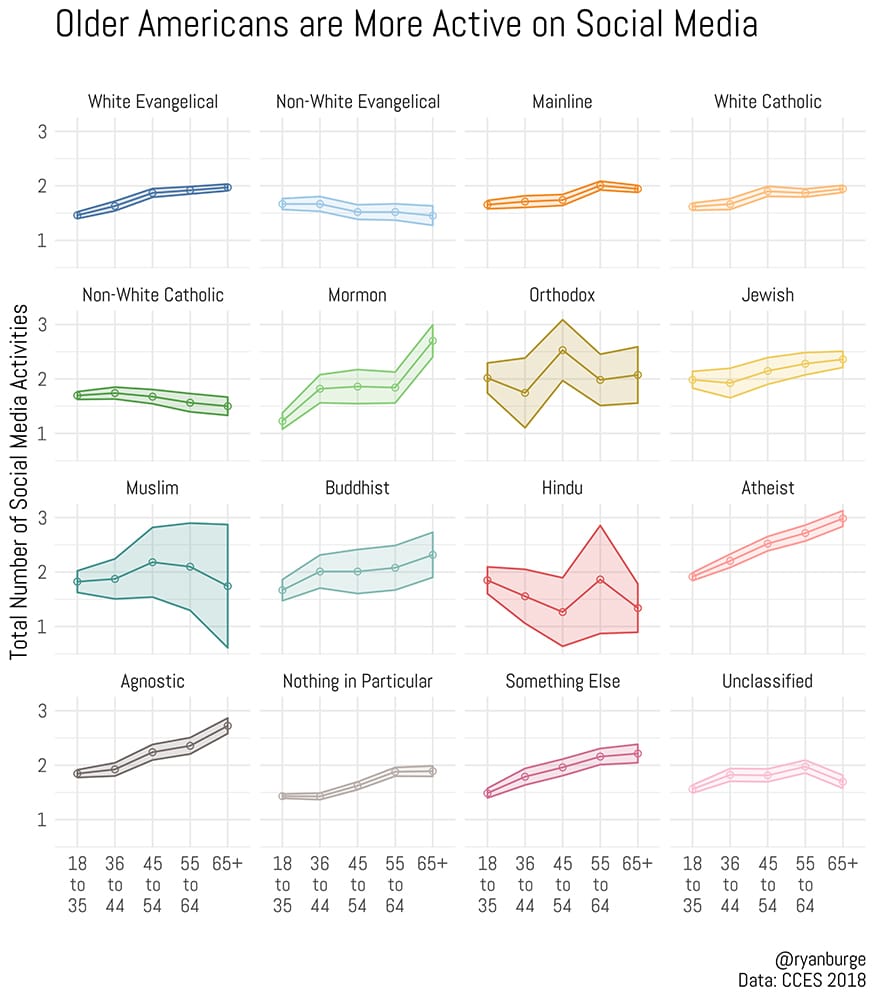

First, who is more active on social media? One would assume that the world of the internet would be dominated by the young, as they are often the first to adopt new technologies. However the data here tells a completely different story.

“Older Americans are More Active on Social Media” Graphic by Ryan Burge

By and large, the people who are clogging up your newsfeed with political stories are some of the oldest Americans, although which older Americans are most active can depend on their religious tradition.

For instance, white evangelicals in their mid-40s or older are slightly more likely to say they’ve engaged in the activities listed above than the youngest white evangelicals. The same is essentially true of white mainline Protestants and Catholics. The pattern breaks down only among older non-white Americans in these traditions who spend less time on social media than their white peers.

Mormons follow a distinct pattern of their own. Social media use is basically flat across the middle of the age spectrum, but the oldest Mormons are extremely active on the internet, engaging in nearly three out of five of the listed activities. The only other group that competes with the oldest Mormons’ social media usage are the oldest atheists, who engage in three of the listed activities; agnostics are not far behind.

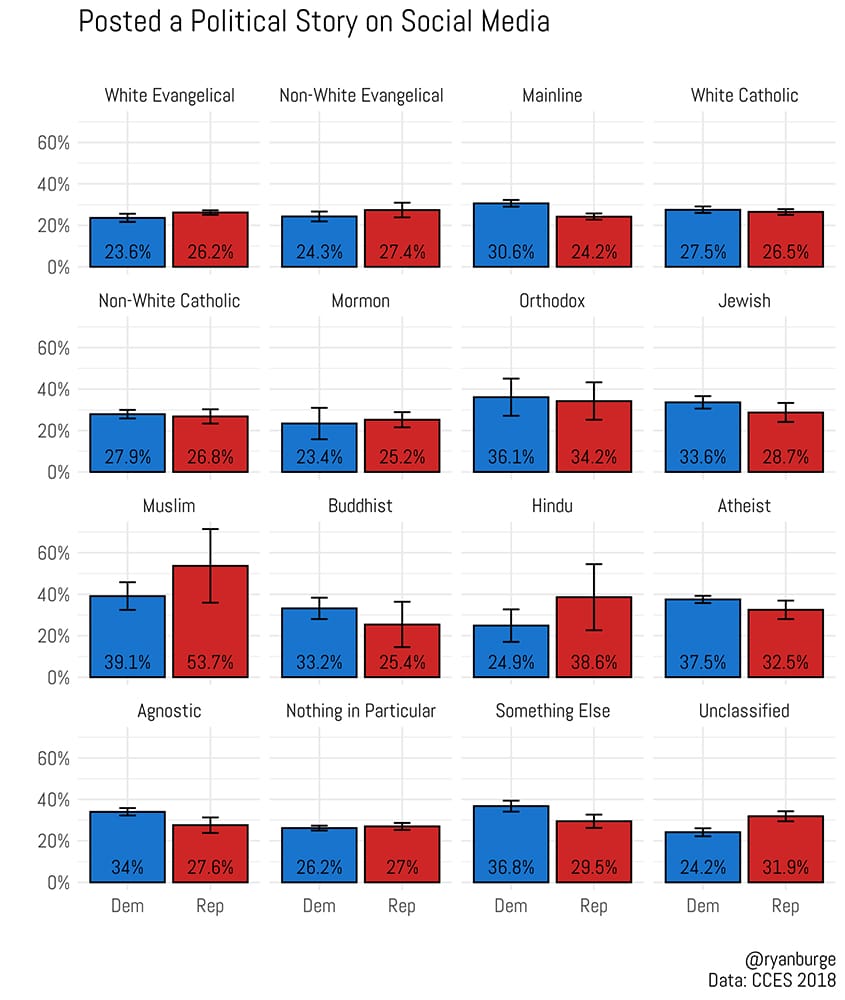

“Posted a Political Story on Social Media” Graphic by Ryan Burge

But a more important question is this: does the phenomenon known as “the spiral of silence” extend to the digital sphere? The spiral of silence refers to the tendency for people who see that their opinions are in the minority in a social situation to be reluctant to voice their dissent to the group. The rest of the group members, meanwhile, assume that silence equals agreement.

I suspected that the spiral of silence is operating among many politically homogeneous religious groups — namely those white evangelicals on the right and atheists on the left.

To test my theory, I looked at just one question from the social media battery: What percentage of each religious group, broken down by Republicans and Democrats, posted a story on social media, thereby breaking their silence?

Though not a lot of differences exist between partisans of any religious group, I did find that Democratic mainline Protestants are more likely to share than Republican mainliners and that atheist and agnostic Democrats are also somewhat more active on social media than their Republican counterparts. The differences, however, are fewer than 10 percentage points.

This indicates that people are more willing to share their political opinions even if they are in the political minority among their religious tradition. But on looking further, the reason for this is disheartening.

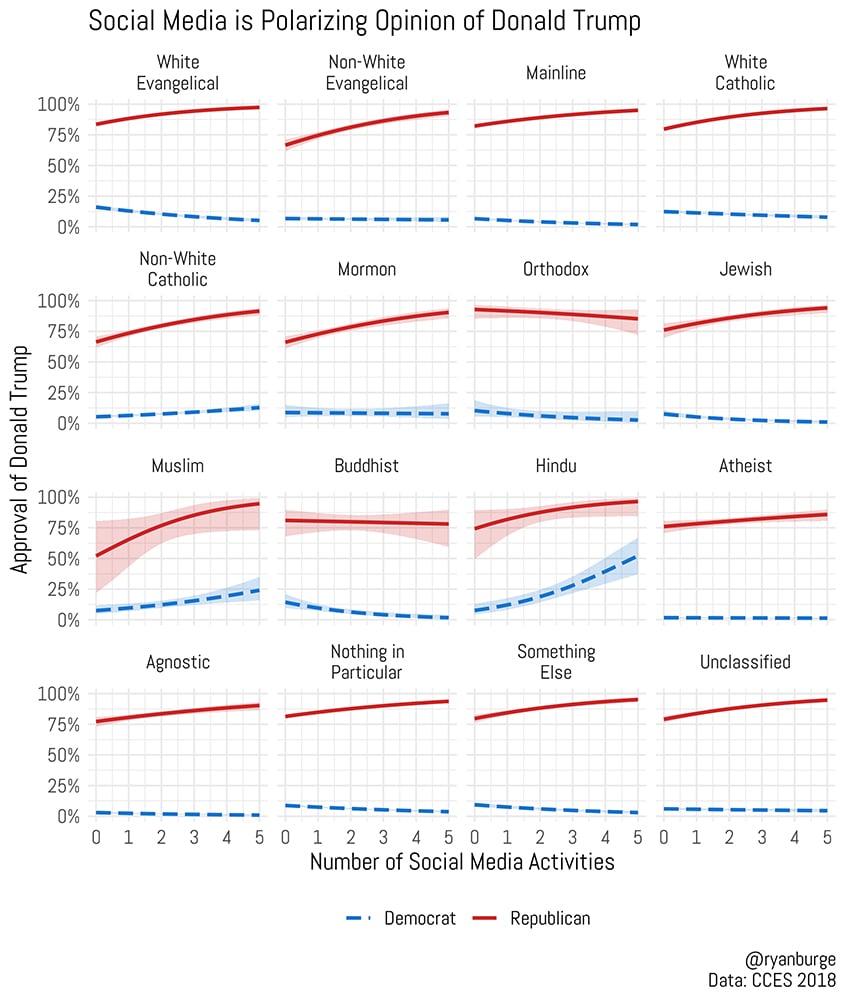

“Social Media is Polarizing Opinion of Donald Trump” Graphic by Ryan Burge

After matching people’s activity on social media with their approval of President Trump, I broke the sample into Republicans and Democrats across sixteen religious categories and visualized the outcome. It turns out that the more polarized one’s view is of Donald Trump, the more active one is on social media.

That’s true for all Protestants and Catholics in the sample. The most active Republicans on social media have nearly 100% approval of Donald Trump, while the line for Democrats is either flat or downward — meaning, at best, social media behavior is not pushing them further to the left.

This gives some support to the spiral of silence still existing in the digital sphere. The most active in your newsfeed are the most “die-hard” for their party. Put another way, the moderates are staying on the sidelines.

The trends hold for religiously unaffiliated and atheist Republicans as well: the more active on social media, the stronger the support for the president.

The picture that emerges here won’t come as a surprise to many who spend time on Twitter: social media is a partisan hell-scape dominated by people who see few shades of gray in American politics.

But if there is good news, it’s that apart from the religious “true believers” of both parties, there is a silent majority likely filled with political pragmatists who see good in both political parties.

My friend and colleague Amanda Friesen once told me about a focus group she was conducting in which she asked why the loudest voices in American politics are also the most extreme. One participant answered simply, “Moderates don’t march.”

It seems that they don’t tweet or post on Facebook, either.