The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks about his opposition to the war in Vietnam at Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, in New York. RNS file photo by John C. Goodwin

(RNS) — On Monday (Jan. 20), scores of Americans will line up at shelters, soup kitchens and community centers for a day of service honoring Martin Luther King Jr., on the holiday celebrating his contributions to American civil rights.

King was, of course, one of the most important social reformers of the 20th century. His struggle against racial discrimination in the 1950s and 1960s led to changes in federal and state laws, including the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act.

But he was first and foremost a Baptist preacher. And his mission to “redeem the soul of America” cannot be understood apart from his Christian convictions and his ability to eloquently articulate those convictions for a nation hobbled by segregation and structural racism.

Richard Lischer. Photo by Les Todd/Duke University

So says Richard Lischer, professor emeritus of preaching at Duke Divinity School whose updated classic, “The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word That Moved America,” has just been reissued by Oxford University Press.

The book, originally published 25 years ago but with a new introduction and some clarifications, examines dozens of sermons and the ways King synthesized the traditional liberal Protestantism he learned at Crozer Theological Seminary and later Boston University, where he earned his doctorate, with his black church heritage.

Lischer spent countless hours poring over King’s typewritten sermons and listening to crackly audiotapes from pulpits across the country. He avoided the heavily edited versions of King’s sermons in earlier published collections so he could hear King’s words as he spoke them, alongside the audience’s reactions.

He found in them a man who believed there were transcendent truths that had the power to change hearts and move them away from the political and social policies of segregation. Among those truths, King focused again and again on a few select themes of love, suffering, deliverance and justice.

Religion News Service spoke to Lischer about the newly revised edition ahead of the King holiday. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How does a white Lutheran professor of homiletics get drawn to King?

It happens this way: A white Lutheran pastor moves South to North Carolina, and has classes with significant numbers of African-American students. I was teaching a seminar on the history of preaching in America. I assigned students to pick a preacher and do some research. One student chose Martin Luther King. She came back and said there was not much out there on King as a preacher. It was all civil rights activism. She had listened to one sermon of King’s to a white church in San Francisco and she thought it was “pretty dry.” I may have been a teenager during the civil rights movement but I knew King was not “dry.” There was something wrong with that report.

So I nosed around and found published sermons that didn’t even read like an African-American sermon. They had been severely edited. Anything that smacked of black concerns, black church worship or criticism of mid-century American values had been removed. So I went to the King Center in Atlanta and examined the typed scripts taken down by secretaries of the churches King served in Atlanta and Montgomery. There was a different story here. Here was a much livelier, more pastoral, more radical church-involved person than the books of sermons indicated. Then I got tapes. Lots of tapes. I sought out people who trained him to preach. I also spoke with the children of his teachers and mentors, with his former parishioners and with many of his associates, including Jesse Jackson, Ralph Abernathy and Wyatt Tee Walker.

As my research grew beyond an interest in his rhetoric, I began to see King more holistically as the voice of a whole movement and as someone whose sermons were nothing less than the first draft of his vision for America.

I found a person who had some incredible rhetorical gifts. He didn’t save them up for a few public appearances or one or two great crusades. It was every Sunday. He didn’t phone them in. He was always doing his very best. Often it was poetic, soaring, inspiring, and it was just Sunday morning. For me, as a white Lutheran, it was my education in black worship. It was church.

Tell me about King’s homiletic genius. What’s distinctive to him?

Part of his genius is that his words are indivisible from his personal being. He’s encoded with the history of black suffering and aspirations. He had a way of conveying that through his voice and demeanor. It’s the utter control he exercised over his body and his voice and his spirit. He always gave the impression of a tremendous amount of power, but he didn’t let it fully break out. Something was always kept in reserve. For the listener, this creates tension and expectation.

“The Preacher King: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Word That Moved America” by Richard Lischer. Photo courtesy of Oxford University Press

He was not chatty in the pulpit. He rarely talked about himself. He had big themes: deliverance, the Exodus story, the importance of love, what it means to be made in the image of God. He didn’t go off on tangents. The images he used were public metaphors. They weren’t personal. He talked of mountaintops and deep valleys, light and hope. He had the gift of seeing rather bleak Southern towns like Selma or Albany, Georgia, as theaters of God’s redemption. He lifted up poverty-stricken towns as places where God was at work transforming the situation. When he talked of the police he said, “We’re tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression.” And when he said it, you could see jackboots coming down.

As he got older and became more angry, he became more of a “puncher” in his preaching. One of his last sermons, which I love very much, is called ‘Why I Must March.” He was in Chicago.

It ends on, “I march because I must, and because I’m a man. And because I’m a child of God.” It’s really powerful. In the book, I transcribe it in poetic form, because it is poetry.

In most sermons I listened to, he began excruciatingly slow, as if out of gas, and gradually works his way up. There is a moment in every sermon I would characterize as a breakthrough. Something has become clear and some new possibility has been revealed. It’s a moment of deliverance. It corresponds to the events of the Exodus. The rhetorical reenactment of this deliverance occurs every Sunday and in every sermon. No exceptions.

You write about how King melded liberal Protestantism with the black church tradition. Give me some examples.

One of the reasons he was uniquely positioned to talk to everyone is that he was trained philosophically and theologically, but he also bore all the marks on his body of the African-American experience. Although he occasionally referenced Hegel or Socrates or Plato, they all fit perfectly into his black voice. Somehow he alchemized them into one message.

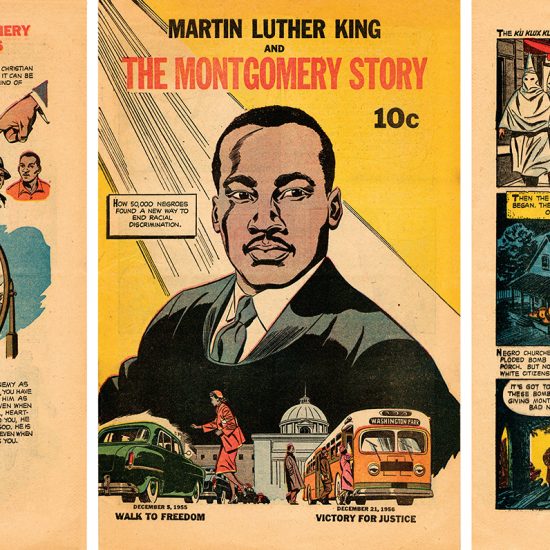

He gave a speech at the beginning of the bus boycott at the Holt Street Baptist Church in Montgomery in 1955. The leaders of the boycott wanted to inspire people to stay off the buses. They turned to this new guy who had just gotten his doctorate from Boston University. What they wanted was a motivational speech. What (King) gave them is an identity speech. He said, “We believe in the teachings of Jesus… There will be no white persons pulled out of their homes and taken out on some distant road and murdered. We are not advocating violence.” The people became very still when he said that. I’ve got a crackly old tape of that speech. A couple of people said, “Repeat that.” It was very sober. This is who we are. It was a beautiful thing he did.

Only toward the middle of the speech he uses one of his flowery, metaphoric flights. He said, “You know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired.” He used the word “tired,” with great understanding. You could hear the people sigh. He’s just 26 years old. He’s in no way tired himself. But he’s able to empathize with the tiredness of people working all day. He pulls that all in and he gives it back to them in a way that shows them he really understands them. At that point the audience begins cheering for a matter of minutes. I count that speech as the beginning of everything for him. With it he became a public man. As he leaves the church one can hear the people crying, “King, King!” I can’t think of another movement in American history so influenced by the spoken word as the civil rights movement.

Is there someone you see carrying forward that tradition, or has it ended?

Today, the civil rights struggle is being carried out on a far more secular, nonsectarian and decentralized platform. A notable exception is the Rev. William Barber, who more than any other preacher has inherited King’s sense of timing, cadence, amplifying power, and with it, the ability to hold a room and to change a room. It’s not merely rhetorical with Barber. He’s making the same case, articulating the same themes as King, plus others that King did not pursue, such as care for the physically and emotionally challenged and the rights of the LGBTQ community. Having said that, one also knows that King occupied a central role in the history of his time in a way no subsequent moral or religious leader has.

One of the reasons I found it important to redo this book was the felt absence of Martin Luther King. He was a leader who was not only attempting to rectify the wrongs of segregation, racism, militarism and poverty, but he was also conveying the meaning of what it means to be a human being and a child of God. King managed to do both — to work at the ground level — housing, poverty, voting, war — but at the same time to do it on a plane that announced, “We all have a destination that is greater than what we can see. We are creatures of God, and God wills us to be delivered of our suffering.” That’s what made his movement unique. Who has spoken of our political conflicts without usurping or selling out the language of faith? When King spoke of the kingdom of God, it was always the expansive, welcoming, force of God at work among us. It was the kingdom that does not separate us from others but brings us closer to God and to one another.