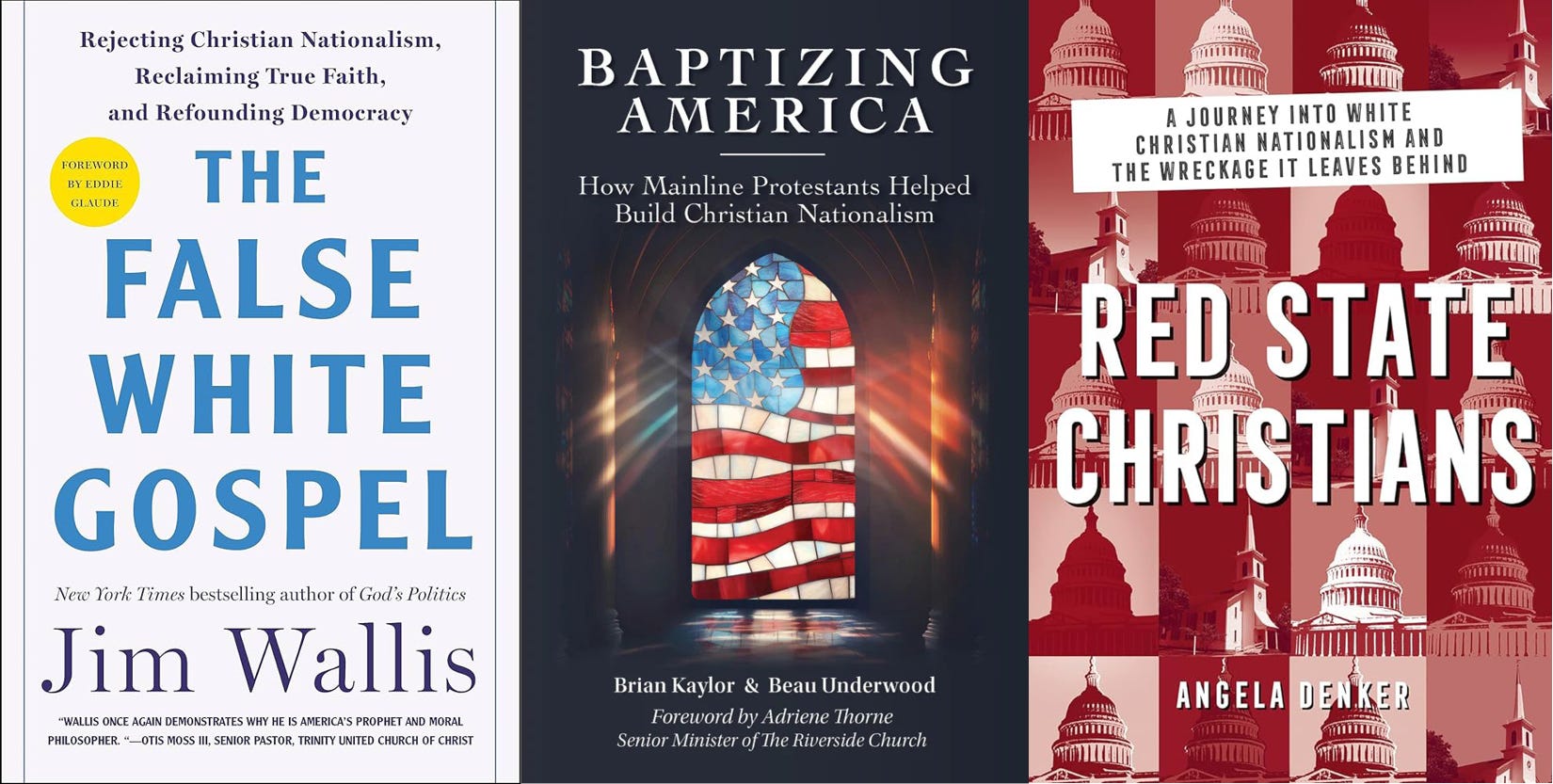

Below is a guest piece from Rev. Angela Denker, a Lutheran minister and journalist. The author of Red State Christians and the Substack newsletter I’m Listening, she also serves as a Word&Way board member.

In the midst of this Holy Week, as former President Donald Trump is hawking “God Bless the USA” Bibles to help pay for his legal bills and finance a potential authoritarian run for the presidency, I had the chance to interview two authors of seemingly divergent books on White Christian Nationalism in America.

Jim Wallis has long been one of progressive American Christianity’s foremost prophets, locating his political activism and writing in the inspiration of the Social Gospel and Jesus’s teachings on care and justice for the poor and oppressed. Originally raised in a conservative White evangelical church, Wallis describes his own calling and mission to ministry as awakened by his experiences in the Black church after he was “kicked out” of his White church in the midst of asking questions about race and justice as a teenager. While doing this work of political activism in response to his Christian faith, Wallis has found himself both invited to the White House and arrested just outside its grounds for his political protests.

As he watches American White Christian Nationalism continue to rise in popularity among conservative evangelicals, Wallis nonetheless retains the term for his own faith, claiming that evangelicalism, when understood according to Jesus’s ministry, finds itself most at home in care for the poor, activism and justice for the oppressed, and advocacy for racial justice in America. Most recently, Wallis has put those teachings into text in his latest book, The False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding Democracy, which is currently available for pre-order and launches on April 2. Wallis also leads the Center on Faith and Justice at Georgetown University and writes the Substack newsletter God’s Politics.

While Wallis continues to describe himself as an evangelical fighting for justice from a progressive point of view and a minister who sees his Christian faith as spurring him into political activism, fellow ministers Brian Kaylor and Beau Underwood from Word&Way have written their own book from a seemingly divergent perspective from Wallis, describing the ways in which mainline Protestants — including Underwood’s own denomination, the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) — have contributed to the current growth in White Christian Nationalism through a privileged position in American politics. Baptizing America: How Mainline Protestants Helped Build Christian Nationalism diagnoses the historical realities that White liberal Christians must contend with in their own churches in order to more fully combat Christian Nationalism. It’s currently available for preorder as well and launches on July 9.

During my conversation with Wallis and Kaylor, I got the chance to ask both authors about the surprising places where their books overlap and to see how both of their books work together to continue to empower Christians to confront Christian Nationalism and reclaim the radical gospel of Jesus. What follows are some enlightening excerpts from our interview, lightly edited for readability and publication, with my own summaries in italicized text.

Jim Wallis (left) and Brian Kaylor (right).

DENKER: I wanted to start out by asking where you both see places of commonality in your work. Jim’s book seems to uplift the ways his life journey has taken him to incorporate Christian teachings into government advocacy and policy, often through partnership with mainline denominations, while Brian’s book is worried about the ways in which government and Christian denominations have worked together in the past to create a fertile ground for growth in White Christian Nationalism. Where do you find areas of agreement in these two works?

KAYLOR: One of the things that [co-author] Beau and I have wrestled with in conversations is that … there is a place for faith-based activism. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and other faith-based activists during the Civil Rights movement, were pushing for an actual democracy where everyone has a voice and everyone is able to participate in the public square, not just his people and his faith. [Dr. King] literally died fighting and marching for poor White folks, arm in arm with rabbis and people of other denominations and people of no faith.

We are not critiquing that kind of faith-based activism. We are making a significantly different critique here. We are not critiquing the prophetic speaking to power, we are opposed to [Christians] trying to be the power. At times, even good-intentioned moderate and progressive Christians got caught up in the vision of, well, maybe we can run this thing.

WALLIS: Yes. Dr. King, he never said, “Because I’m a Christian, you have to listen to me.” He knew he had to win the debate. He was not hesitant to bring his prophetic faith to the debate, and as you said, bring his faith to speak truth to power.

White Christian Nationalism is not about that kind of faith, it’s really about an idolatry that wants to gain power. The name spells the problem. [White Christian Nationalists] took the most inclusive, welcoming message in the history of the planet, Christianity, and they made it White.

Wallis went on to explain that, in his view, the way to defeat White Christian Nationalism is for Christian groups to return to their founding theologies and faith, and to remove the focus on race-based exclusion, especially in groups like “White mainline” Christians, “White Catholics,” and “White evangelicals.”

WALLIS: The problem is that they’ve become more White than they have the second word, which is an idolatry. I want to put “evangelical,” “mainline,” and “Catholic” first before the “White.”

DENKER: You both spoke about the ministry and activism of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In the past, I’ve seen conservative White Christian leaders seem to try and use King’s sermons to support their own view of a post-racial America. But recently some right-wing Christian pastors like John MacArthur have attempted to claim that King wasn’t a Christian at all, but a Communist.

WALLIS: I’m not surprised [they’re claiming King wasn’t a Christian] because they’re lying about everything and manipulating everything. The opposite of truth is captivity. King’s message was [the opposite of White Christian Nationalism]. He thought the churches should be a model for society, not control society. He was very pluralistic. [King’s] Black church took me in. … I’m not going to worry about the distortions [of White Christian nationalist leaders]. Every movement has to decide who they can persuade and who they must defeat.

Wallis seemed to distinguish here between corrupt religious leaders like MacArthur, who Wallis described as “militant religious political people who just want power,” and the ordinary American Christians for whom he wrote his book, in hopes of refocusing American Christians on the freedom and hunger for justice of Jesus’s gospel.

KAYLOR: The truth is that King was never accepted [by leaders like MacArthur and other White conservative pastors] because of the Whiteness [of their theology]. MacArthur has also spoken in support of slavery.

Help sustain the journalism ministry of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

Martin Luther King, Jr. and other religious leaders at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. (Original black and white by Rowland Scherman. Colorized by Jordan J. Lloyd.)

DENKER: Much of the inspiration for Jim’s book and depiction of The False White Gospel comes out of his experiences with the Black church. Brian, you and Beau have critiqued at times the political activity of the Black church, when Democratic politicians have campaigned in Black churches on Sunday mornings. Jim, tell me how you would respond to those critiques.

WALLIS: Politicians always want to use religion for their own purposes, and all churches have to be wary of that. But in Ohio, 6,000 Black voters have just been purged from the voter rolls. Black churches are telling everyone on Sunday in their churches who is registered to vote and who’s not. It’s nonpartisan in that sense. We are training poll chaplains to de-escalate conflict where it occurs and where the right to vote is being threatened.

Wallis went on to describe his work with Faiths United to Save Democracy, a movement focused on voter registration and non-partisan voter education that has partnered with many Black denominations and mainline denominations like the AME Church, Conference of National Black Churches, Church of God in Christ, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), NAACP, National Baptist Church USA, National Council of Churches, National Latino Evangelical Coalition, and United Church of Christ, as well as the progressive Christian organization founded by Wallis, Sojourners.

WALLIS: Personal and public faith have a more holistic notion in the Black church.

Wallis alludes here to the history of the Black church as a hub for community organizing and activism in Black communities, especially urban centers.

DENKER: Brian, you have critiqued these appearances by politicians in Black churches in the past. Do you make an exception for the Black church when it comes to your understanding of the role of Christianity in American government? Why or why not?

KAYLOR: One of the things that is really important is that we don’t fall into the partisan trap. That’s the difficult work of doing long-term Christian witness in America: speaking truth to power regardless of who is in power.

I’ve been greatly concerned about the misuse of holy spaces. I find that to be problematic even when it’s politicians who I’m voting for. I’ve been critical of politicians who I also voted for. It’s up to churches to protect our holy space and make sure it’s not exploited.

DENKER: While lifting up the witness and activism of leaders like Dr. King and the history of the Black church as fighting against poverty and oppression, what do you do with the existence of predominately Black churches and Black pastors in America today who are preaching the “prosperity gospel”? Or megachurches that are led by pastors of color or predominately attended by Christians of color but who also end up supporting Christian Nationalist theology and ideology?

WALLIS: That’s something I often hear in my work with young Black pastors and activists. They say, “You’ve gotta go tougher on those Black churches.”

We have to remember that Dr. King only ever had a minority of Black churches on his side. The majority of them didn’t risk and didn’t march. When he came out against the war in Vietnam, he was even criticized by the Civil Rights movement for taking on war, racism, and poverty.

In some Black churches, you can see seeds of the White heresy.

Wallis spoke of being inspired in his work with a group of young Black activists and Black Lives Matter protesters who had been gathered by Trinity United Church of Christ’s senior pastor, Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III, whose father was a pastor and colleague of Dr. King’s in the Civil Rights movement. He mentioned especially being inspired by the story of activist Brittany Packnett Cunningham, the daughter of two pastors who had drifted away from the church but had become reconnected to her faith during racial justice protests in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, after the police killing of Michael Brown.

In response to the same question about critiquing Christian Nationalism within non-White majority spaces, Kaylor compared it to his and Underwood’s work to help liberal White Christians grapple with mainline Christianity’s role in preparing the ground for White Christian Nationalism by their privileged place in American government historically.

KAYLOR: If you look at the sociological research on Christian Nationalism … it always exists on a continuum. There’s a scale. Most of us are somewhere on that continuum.

If you grew up in a church in the U.S., Christian Nationalism has been so embedded. [Conservative denominations like the Southern Baptist Convention] are producing so many of the educational materials. Many of the students at [SBC] seminaries are not Southern Baptist, and many of them are students of color. They’re being impacted by this ideology.

Christian Nationalism can be a temptation everywhere, especially when you’re in the empire. All these heresies can show up anywhere.

I feel like I’m still detoxing myself, and I’ve been researching this and writing about it for years.

Wallis then referenced a story he tells in The False White Gospel about a meeting he had with young pastors in Atlanta, describing how the White pastors were more worried about security and the Black pastors concerned with support for their witness and prophetic speaking to power regarding the rise of Trumpism and White Christian Nationalism. Nonetheless, Wallis affirmed that his hope is for a “remnant church: a minority of White believers who are ready to stand alongside prophetic Black and brown church leaders to create a new American church.”

KAYLOR: I don’t think either of our books are good church growth strategy books. I don’t think it’s going to be popular [to divest from the power of White Christian Nationalism].

WALLIS: [chuckling and agreeing, affirming the call to prophetic witness] I was going to call this book, “Do we believe it or not?”

Get cutting-edge analysis and commentary like this in your inbox every week by subscribing today!

(Josh Eckstein/Unsplash)

DENKER: I’m curious about the ways your two books address the growing group of non-religious Americans. How do you see your work with secular Americans to fight Christian Nationalism?

KAYLOR: Several times a year I testify in the Missouri legislature against efforts to codify Christian Nationalist proposals. Usually, pastors and activists will speak in support of these bills and then speaking against the bills is usually myself, an atheist or two, and a couple of Satanists. That’s the coalition. … I have found that it is even more important that I show up to that space. If I don’t show up, the only thing people hear from Christians is that we don’t care about religious minorities.

WALLIS: Sometimes the answer to bad religion is no religion. I love the nones. Most of my students [at Georgetown] fall into that category. They aren’t necessarily secular; they just don’t want to affiliate. When they hear about a different kind of faith, they’re interested in it.

Many of my students have never heard about Catholic social teachings.

I want those pastors who are afraid to speak the truth [about Christian Nationalism] to know that while they may lose numbers, new people are going to come to them. I think this Jesus [who speaks against Christian Nationalism] is going to appeal [to the nones].

To conclude our conversation, I asked Wallis and Kaylor how they manage their own activism work and its requisite need for access to power with the need to speak truth to that power and not become captive to it, as has been the case in White Christian Nationalism. Both writers spoke frankly about the difficulty of this challenge in their own work and also how their faith in Jesus gives them clear witness about why it’s important to carry on anyway.

Wallis spoke about the real pressures of power in the context of heading to a meeting at the White House that very afternoon.

WALLIS: The feeling of the principalities and power is palpable inside the White House and in Congress. [The principalities and powers of evil and idolatry] want to make you stutter and not tell the truth.

For me, every movement for justice does this dance. Dr. King knew that his base was on the outside, but he had to cultivate presence on the inside.

Wallis retold another story from The False White Gospel when due to his arrest history he was denied access to the White House and he had to have a special escort.

He said he’s also seen too many pastors have the opposite problem of refusing to engage in necessary work with government officials out of a desire to be “righteous and good and prophetic.”

That’s really a choice of privilege. We have to learn how to do that dance, to be faithful on the inside as well as on the outside.

Money does always get in the way. The budget is a moral document, and we have to push back and must do it when we are on the inside.

KAYLOR: You can get some great things done [with access to power], but access cannot become the goal. That cannot be the only thing that we’re shooting for.

WALLIS: Access has a cost.

KAYLOR: There was a point for you, Jim, when you lost that access, and you were willing to lose that access for your witness.

Kaylor references Wallis’s opposition to the Iraq War, which meant he lost access to then-President George W. Bush who he had been working with on anti-poverty initiatives.

WALLIS: The access can bring benefits, but there’s got to be something more to it.

In Washington, access is the goal. The goal is not to get things done. The goal is to have the conversation. Everyone is rated on how much access they have, and they don’t want to risk losing access.

Wallis then references a recent conversation he had with Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry, who encouraged him to always “go to the text” of the Bible and “let Jesus do the talking,” even when working in political faith-based activism. He spoke about Jesus’s conversation with a young lawyer and remembering that your neighbor probably doesn’t live in your neighborhood.

KAYLOR: What I have enjoyed is that even though we come at this question so differently [regarding the role of political activism and the historic growth of White Christian Nationalism], we are quoting a lot of the same people. Both of our books are concerned with the threat to democracy of White Christian Nationalism and the threat to the Christian witness.

In the end, we are suggesting some of the same things: educate yourself, improve in your own context, and tell the truth.

We’ve recognized the same threat. And both of us are just trying to start wherever we are to make a difference.