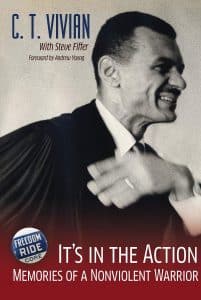

Before passing away last July, famed civil rights activist C.T. Vivian started working on his autobiography. That work, finished by coauthor Steve Fiffer, will be released next week. In the book, It’s in the Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior, Vivian reflected on his role in key civil rights moments. And the Baptist minister suggested the “origins” of his character could be traced to his early years in Boonville, Missouri.

While the advocacy of Vivian in civil rights campaigns in Nashville, Selma, Chicago, and elsewhere is well documented, he offers new details about his early years in Missouri. Despite his many honors in other states for his work — and his recognition with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013 — Missouri has ignored this native son.

While the advocacy of Vivian in civil rights campaigns in Nashville, Selma, Chicago, and elsewhere is well documented, he offers new details about his early years in Missouri. Despite his many honors in other states for his work — and his recognition with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013 — Missouri has ignored this native son.

In the book, Vivian started his story by grounding it in his family’s history of enslavement — and their push for education.

“First came the darkness. Slavery,” he wrote. “After the darkness of slavery came education.”

Vivian traced the story back to his maternal great-great-grandfather, Al Sampson, who was born enslaved and forced to farm in Howard County just across the Missouri River from Boonville. Sampson fought for the Union Army in the Civil War and then returned to Howard County to farm.

“When we came out of slavery, we continued to farm. Because that was the work we knew,” Vivian wrote. “But it was different now that we were free. We didn’t have to work for anyone else; and, when possible, we could buy farms for ourselves.”

Vivian noted that after freedom, his great-great grandfather took the last name Woods from his mother because he refused to keep the surname given him that was that of his enslaver. (Vivian added he does not call enslavers “masters” but instead refers to the enslaver of his ancestor as “the murderer who had owned him.”)

Vivian recounted his maternal great-grandfather — who he knew — had also been born in slavery and after the War was briefly the principal of an all-Black school. But that man, David E. Woods, was fired for teaching algebra.

“The elders on the all-White school board couldn’t do algebra themselves, so they weren’t going to allow Black children versed in abstractions and equations to upstage them,” Vivian explained. “Curious kid that I was, I would ask him about slavery. Having been freed when he was pretty young, he didn’t have much to say.”

By the time of Vivian’s birth in 1924, his family still farmed in Howard County. But they lost their land when the Great Depression hit, and his parents separated. Vivian then lived in Boonville with his mother, Elizabeth Euzetta Tindell, and her mother, Annie Woods Tindell.

Situating his story in the context of that place, Vivian in the book noted some of the history of Boonville as the easternmost stop on the Santa Fe Trail and a place settled by two of Daniel Boone’s sons. And he mentioned the Battle of Boonville and the back-and-forth control of the city during the Civil War.

In the decade before Vivian moved to town, he noted, the city’s population jumped 40% to about 6,500 people “thanks to all the farm failures.”

“We lived in a wood-framed house on Water Street,” he added. “The property ran down a hill to the railroad tracks along the Missouri River. When the long freight trains rolled by, my grandmother would sit me in an upstairs window and make me learn my numbers by counting boxcars. Sometimes there were two hundred or more.”

Building of Character

Vivian also mentioned his love of books and religion starting in Boonville, especially from the influence of his grandmother.

C.T. Vivian in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 23, 2013. (Adelle M. Banks/Religion News Service)

“My own sense of faith was born from going with her to Church of God the Christ in Boonville,” he recounted. “I loved the church from the earliest age. How much? One Sunday when I was five, my grandmother told me I had to stay home from services. I was so disappointed that I ran out of the house and lay in a rut in the road. I was going to let the cars run over me if I couldn’t go to church.”

“I don’t think you can understand African American history without talking about religious life,” he added. “In fact, I don’t think you can understand any group that has been enslaved without talking about faith in God. Case in point: Moses and the Jewish people.”

And this faith would impact his view of America that he would later devote his life to reforming.

“We believed that somehow God was going to take care of us,” he wrote. “We had to believe — because there sure wasn’t much else in the country that said we should survive. Even though America was a democracy, we knew it wasn’t a democracy for us; it was supposed to be a Christian culture, but it wasn’t.”

“Ironically, the saving grace for us was that Blacks and Whites weren’t in the same church. With few exceptions, Whites didn’t want us praying with them. And for Southern Whites in particular, the church wasn’t really God’s, it was theirs. By having our own churches, we could have our faith without any people who opposed the movement telling us we had to obey them,” he added. “We were Christians, and it was God who would save us from the terrible conditions we endured. It’s no surprise that the leadership in the civil rights movement came out of the church.”

Vivian saw these and other values forming the character and personality he would later need during the civil rights movement.

He recounted the story of an experience at the house on Water Street where the shadows between the houses darkened the landscape. As he ran around the house when he was four or five, he suddenly saw “a ghost” near a walnut tree and grapevine. But he ran toward it to grab it while also hoping it was not really a ghost.

“Instead of running away, I kept reaching until I grabbed that ghost’s sheets. Or, I should say, the sheets my mother had hung up outside to dry,” he wrote. “My imagination had taken hold of me, but I learned an important lesson that served me well in facing the likes of Sheriff Jim Clark in Selma thirty-five years later: You can move toward danger. You don’t have to be afraid.”

“Later, I’ll relate how I tried not to back away from sheriffs and private citizens alike wishing to do harm to me and those I led,” he added. “It’s not an exaggeration to suggest that some of that confidence — some might call it foolhardiness! — had its origins in Boonville.”

When he was six, their house burned down. His mother and grandmother decided to leave “segregated Boonville” and move to Macomb, Illinois, in hopes of better educational opportunities for Vivian with integrated public schools and a university in town. In Illinois, he started his activism against segregation and felt the call to ministry.

Vivian eventually attended American Baptist Theological Seminary (now known as American Baptist College) in Nashville, Tennessee, where he and other students — including John Lewis, James Bevel, and Bernard Lafayette — helped lead the Nashville sit-ins before partnering together across the nation for more civil rights efforts in Selma and elsewhere. After Vivian died last July 17, Lewis died later the same day.

It’s in the Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior by C.T. Vivian and Steve Fiffer will be published March 16 by NewSouth Books.