A regular Saturday ritual during my childhood years was a trip to the video store. We would rent a movie or game that would be our entertainment for that night. Every borrowed VHS tape came with a stick that read, “Be kind. Please rewind.” This, I came to understand, is what kindness meant: do the simple, nice things that make other people’s lives easier. Only jerks fail to rewind (and then they pay a fee to the video store because justice will be served!).

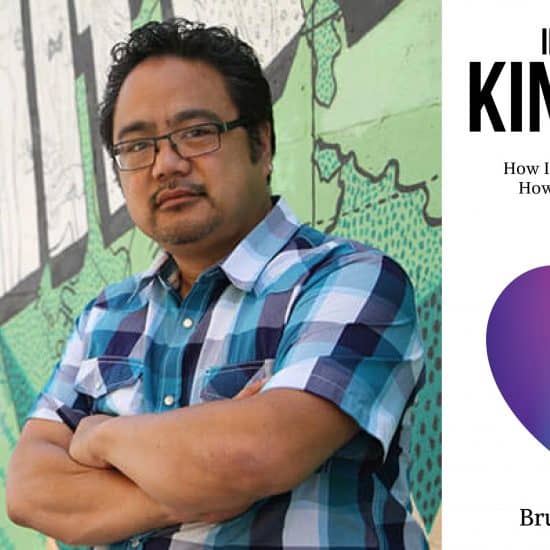

It is such superficial understandings of “kindness” that Bruce Reyes-Chow argues against in his new book, In Defense of Kindness: Why it Matters, How it Changes our Lives, and How it Can Save the World (Chalice Press, 2021). He advocates for a more robust concept that leaves a powerful impact on us and the world by guarding against our tendencies to either denigrate the humanity of others or reduce them to one dimensional caricatures that denies the inherent complexities of being human.

It is such superficial understandings of “kindness” that Bruce Reyes-Chow argues against in his new book, In Defense of Kindness: Why it Matters, How it Changes our Lives, and How it Can Save the World (Chalice Press, 2021). He advocates for a more robust concept that leaves a powerful impact on us and the world by guarding against our tendencies to either denigrate the humanity of others or reduce them to one dimensional caricatures that denies the inherent complexities of being human.

“To be kind,” he writes, “is to accept that each person is a created and complex human being — and to treat them as if you believe this to be true.”

Such an approach to our actions and relationships requires us to respect the status of each person and try to empathize with their circumstances. In this way, others have a claim on us. They cannot be ignored or dismissed. They must be appreciated and understood by us as fully as possible.

If this sounds quite similar to Jesus’s exhortation to “do to others what you would have them do to you” (Matt. 7:12) or his commandment to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:31), you are not mistaken. Reyes-Chow is a Presbyterian pastor and references his faith and vocation throughout the book, but he is intentionally trying to speak to a broader audience. His ideal of “kindness” reflects the demands of the Gospel without any of the Christianese, presumably in the hope that such good news will garner a wider hearing.

He also does not want kindness to be mistaken for tolerating injustice or excusing bad behavior from others. Instead, he sees kindness as offering two correctives. First, it offers a guide to how we engage others, be that in our private lives or the public square. It is an ethic we embody no matter the circumstance. Second, it prevents us from overly simplifying problems in ways that prevent root causes from being addressed. Dismissing a bad actor as either a lone individual or incapable of redemption are both easy outs that avoid the hard work of changing systems or seeking true transformation. Rev. Reyes-Chow’s version of kindness is not about whether confrontations occur and redress is sought but the manner in which both are pursued.

Overall, the book is more fun to read than one might assume from the title. It is not a dry, logical argument unpacking what kindness means. Rather, the tone and content remind you of an excited, perhaps even intense, conversation you would have over dinner with close friends. There are humorous examples, clever digressions, a few unnecessary tangents, and, overall, an argument being made by someone whom you trust and believes cares deeply about you.

Reyes-Chow does not present himself as the expert on kindness but as a fanatic, someone who excessively believes in it. That zeal flows out of his own experience of what kindness makes possible and his own struggles to meet its expectations.

T he book is relatively brief (110 pages) and each chapter is fairly short. Thus, it can be digested in one sitting by someone eager to glean wisdom or utilized as devotional by a reader wanting to savor its ideas and reflect on its encouragements. It is also our July Book Club selection! If you decide to bite off the challenge of becoming more kind, then reading this book is the perfect first step and signing up for a group discussion time is a great second one. You can also listen to our editor-in-chief, Brian Kaylor, interview Bruce Reyes-Chow on our new podcast, Dangerous Dogma.

he book is relatively brief (110 pages) and each chapter is fairly short. Thus, it can be digested in one sitting by someone eager to glean wisdom or utilized as devotional by a reader wanting to savor its ideas and reflect on its encouragements. It is also our July Book Club selection! If you decide to bite off the challenge of becoming more kind, then reading this book is the perfect first step and signing up for a group discussion time is a great second one. You can also listen to our editor-in-chief, Brian Kaylor, interview Bruce Reyes-Chow on our new podcast, Dangerous Dogma.