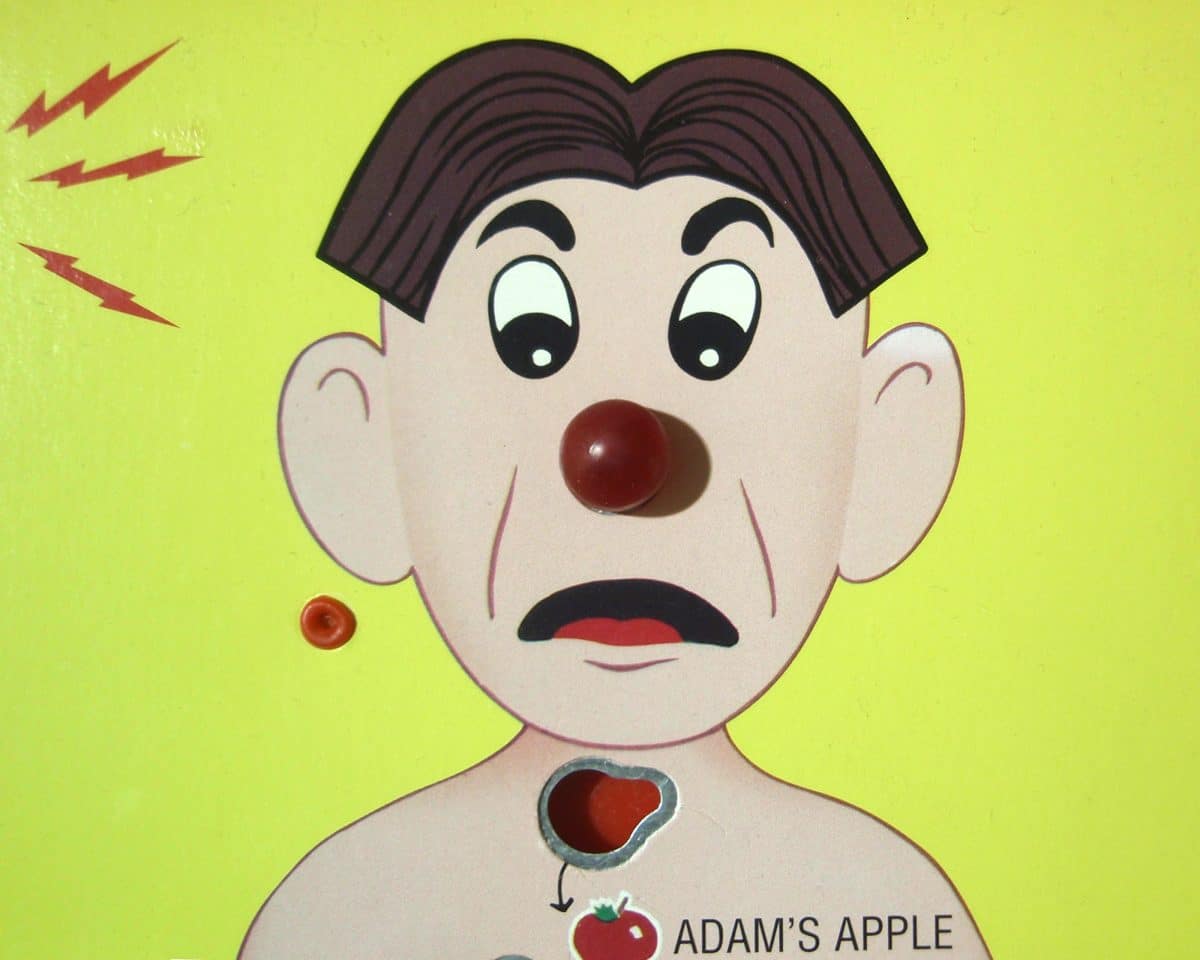

There were two games that I hated playing as a kid. No, one was not the eternally long game of Monopoly — my cousin and I used to just slide it under the couch when we wanted to take a break and slide it back out later. One of the games that drove me crazy was called Perfection. I can still feel the anxious pit in my stomach when that timer started going and I frantically scrambled to put all the pieces in the right place. If you did not do it just right, the machine would “pop” sending the pieces (and your shattered childhood dreams) in different directions. The other game was called Operation. In the game Operation, one is tasked with taking out little plastic body parts from small recesses within a patient on the operating table named “Cavity Sam.” The parts all have catchy names like “Adam’s Apple,” “Wrenched Ankle,” and “Spare Ribs,” with a symbolic plastic piece to match. If your hand was not steady enough, the metal extraction tool would hit the metal-lined side of the cavity and Sam’s nose would light up bright red, accompanied by a horrible buzzing noise.

Sarah Blackwell

In thinking about Christmas, giving, and games this year, I was struck by how we have given our kids some of the same narratives as those dreaded games, Perfection and Operation. With Perfection there remains an underlying assumption that if they put every piece in just right, they can turn off the timer and somehow “win” at life. The frenetic pace is rewarded when each piece of their college application or job resume is just right. Unfortunately, most of the time they end up a frantic mess just staring at the pieces of their life as they go tumbling all around them. Perfection remains elusive but is still the name of the game.

What I really have been thinking a lot about, though, is Cavity Sam. I believe we are teaching our Christian young people a version of reading the Bible that closely resembles the game of Operation. One of the biggest things I have learned from teaching young adult students the Bible is that they have little concept of the “connective tissue.” They know some verses or stories (simplified or taken out of their original context), but they do not understand how or why they function in the larger story. Like the stylized versions of the body parts in Operation, they know how to carefully pluck out quotations to serve a purpose. They might believe this is the verse for “butterflies in the stomach,” this is the one for a “broken heart,” and this one might even serve as a “wishbone.” They develop the air of confidence of an accomplished surgeon when they are only barely qualified to help Cavity Sam. This false sense of certainty can be dangerous to their spiritual life — they stop asking questions and being curious when taught only a simplified “if… then” faith. Without tension and curiosity, their spiritual growth is stunted, and biblical knowledge is foreclosed.

Compare the stylized Operation heart with how an actual heart looks. We have sanitized the biblical stories so much that students are literally shocked when they see the sometimes gory inner workings of the Bible. There are often taught none of the messy parts; everything is sanitized and in its own little place. The problematic bits can be skipped over (two different people killed Goliath?) and only certain parts canonized. Things that they assume are in the Bible are not or are in a radically different form than expected. This is made even worse by the proliferation of Bible apps where it is too easy to look up individual verses without even seeing them as part of a larger story. There is something gained when students hold actual Bibles (preferably good study Bibles) and can see the different books, authors, order, and length.

In our hopes to simplify, sometimes we even look to join things that do not belong like the one rubber band piece you had to insert in Operation called “Ankle Bone Connected to the Knee Bone.” Oftentimes, when we should be dissecting to examine more closely, we try to reconcile things that do not belong together. We take the rubber band and try to wrap it around all the gospel stories, for example, without stopping to ask the more powerful question: “Is there a larger reason the same story is told four different ways?” Instead, we must equip them to wrestle, question, and investigate rather than just seek the quick fix.

Mykl Roventine / Flickr

When they start reading the Bible in large chunks for themselves, students are struck by all the things in between the stories in their children’s Bible: Why are there two creation accounts? Noah did what after the flood? David had how many wives? Instead of fearing their curiosity, we should embrace it and lead them through paths of discovery, just like a budding surgical intern might learn at the side of their attending. We would not leave them stuck thinking Operation is how an actual operation works; we cannot do the same with biblical literacy. Bible stories may be for children, but the biblical narrative is for young adults. Just as Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 13:11, “When I was a child, I spoke as a child. I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became an adult, I have put away childish things” (NRSV). We cannot be content to let our adolescents’ understanding of the Bible remain at the children’s Bible level.

Just like we understand the games of childhood as over-simplified, though, we do not make the same clarification to our older children and teens about the Bible stories they have learned as a child. I think many parents are afraid of the big questions that they feel unequipped to deal with. Instead of engaging and challenging our students while they are under our roofs, we remain satisfied in their conversion and allow them to slip away from faith formation because at some level we feel like they have learned all the things they “have to” know for salvation. Maybe it is because we, as adults, have also been taught that Cavity Sam Bible reading is all there is, too?

What if this coming year we engaged and challenged our students and taught them about more than just the highlights of the biblical texts and a couple of “feel good” verses? What are some simple ways to do that? One way is to choose a gospel account to read together one chapter at a time each evening. Talk about what the writer focuses on and what is omitted. See Jesus as the author of each gospel did. Listen to Andrew Peterson’s Behold the Lamb of God, which connects the entire biblical narrative into one cohesive unit. Try out a podcast like The Bible for Normal People where Peter Enns and Jared Byas “ruin” our preconceived notions about a book of the Bible. When using a famous Bible quotation, take a couple of moments to look at the verses directly before or after to better learn the situation in which they were originally used. Check out an illustrated Bible dictionary or handbook from the library to put the stories in greater context and appeal to visual learners. Watch some of the videos on the Bible Project website that explain the background and theology behind each of the books of the Bible.

Take the position that you are both learners on a journey by asking open-ended questions and being okay with uncertainty. We cannot teach them everything about the Bible, but we can teach them how to learn about the Bible on their own. Thus, it is time to remove the batteries out of those blasted games of Perfection and Operation, and venture forward into the deep mysteries of the Bible without all the pieces having to fit perfectly, with no “butterflies in the stomach,” and definitely without that obnoxious buzzing noise telling you that you are doing it wrong.

Sarah Blackwell is a contributing writer for Word&Way and a 2020 Graduate of the Gardner-Webb School of Divinity. She currently teaches in the religion department at Wingate University in Wingate, NC. She has worked with youth and young adults at Providence Baptist Church in Charlotte, NC for almost 20 years. She is the author of God is Here, an illustrated spiritual formation book for children based on encountering God in nature, available this spring. For ordering information and to follow her writings go to proximitytolove.org