(RNS) — Alex Lang thought he was done with the pastorate for good.

On Sunday, Aug. 27, Lang bid farewell to the congregation at First Presbyterian Church in Arlington Heights, Illinois, where he’d served for a decade.

His final sermon done, Lang sat down and typed out some thoughts on why he left not only First Presbyterian but the pastorate altogether. Lang posted that essay a few days later on his website, thinking his few hundred regular readers might be interested.

He was partly right. His regular readers were interested. And so were about 350,000 of Lang’s colleagues.

Lang’s essay, entitled “Why I Left the Church,” went viral — and prompted a national conversation among clergy about the pressures of the profession and how they talk about those pressures. Over coffee and in Facebook posts and denomination offices, Lang’s essay became the topic du jour for clergy around the country. Some resonated with his concerns, while others saw his leaving as a lack of faith.

The Rev. Alex Lang. Courtesy photo

“I’ve done more than 50 articles,” said the 43-year-old Lang during an interview at his home outside of Chicago. “Usually nobody cares.”

His more recent essay became a blank slate for people to write their own experiences on. Many of those experiences are difficult — as pastors have become burnt out caring for people’s souls amid the decline of organized religion known as the “Great Dechurching” and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Alex raised issues that are relevant and resonated with clergy serving congregations and other institutions,” said Rev. Craig Howard, executive presbyter of the Presbytery of Chicago, which First Presbyterian is a part of. “These issues include isolation, organizational calcification, burnout, and bullying.”

After reading Lang’s essay, Howard said he emailed other clergy in the Presbyterian Church (USA) in the Chicago area, inviting them to meet up and talk. That meeting, he said, led local leaders to work on some resources to help pastors with spiritual care and mental health issues.

In his essay, Lang talked about the burden of knowing his congregation’s secrets and their sorrows — which became, at times, more than he could bear.

“What you don’t realize is that, over time, the accumulation of all that knowledge starts to weigh you down,” he wrote. “Your mind is a repository for all sorts of secrets and, if you’re human, you feel sympathy and empathy for their suffering.”

That portion of Lang’s essay resonated with the Rev. Devyn Chambers Johnson, co-pastor of Covenant Congregational Church in North Easton, Massachusetts. She said it’s hard for congregation members or those outside the church to understand that part of a pastor’s life.

While helping professionals like therapists or counselors also support people in crises, they don’t do so on the scale that a pastor does, something she said her husband and co-pastor, Ryan, helped put into perspective.

“Therapists only have a few dozen people to care for,” she recalled her husband saying. “At church, you have hundreds of people that you help with their hurts and griefs. That is something people don’t realize.”

Add to that the logistics of the pastorate — preparing sermons, raising funds, working with committees, and dealing with all the small details needed to keep a congregation running — and it can be a lot.

Chambers Johnson said she felt more prepared for the burdens of the pastorate because her father was a pastor — so she knew what she was getting into. She also said caring for people in her church is a privilege — that some of the most holy moments of her life came when she was present with people in grief or crisis.

“That’s the part of the job I would not trade for everything,” she said.

Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Center for Religion Research, said adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic — and responding to the Black Lives Matter movement, political polarization, and the reality that congregations are shrinking and aging — has all taken a toll on pastors.

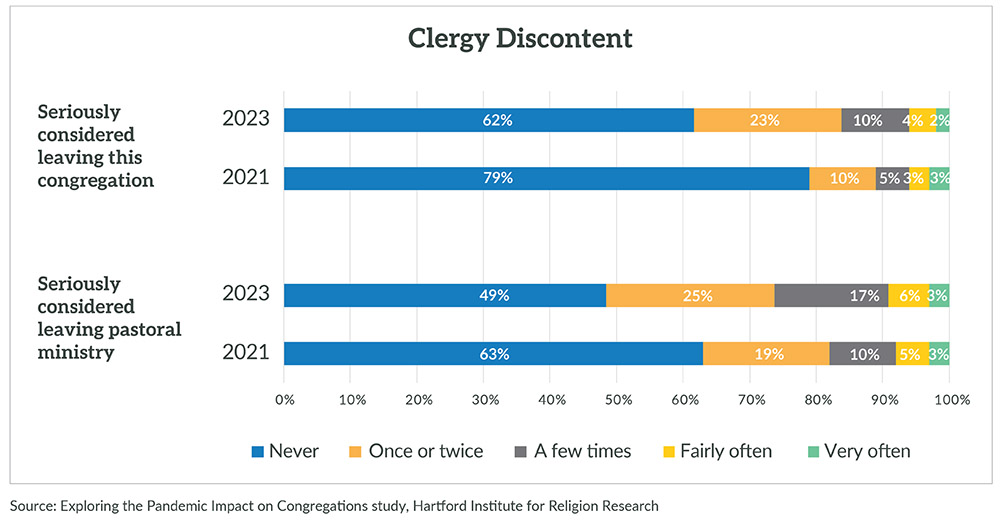

Thumma, who has been studying the impact of the pandemic, said a growing number of pastors have begun to think about leaving the pastorate.

“It’s absolutely clear that people are stressed and tired and worn out,” he said. “And they think about quitting. But they are not giving up.”

“Clergy Discontent” Graphic courtesy HIRR

Thumma said only 3% of clergy think about leaving all the time — a percentage that hasn’t changed much in recent years. And he said that overall, clergy have a fairly positive outlook on life, according to a recent study done by Hartford.

Nathan Parker, pastor of Woodmont Baptist Church in Nashville, said he’d had mixed reactions to Lang’s piece, which he said circulated widely among his Southern Baptist colleagues. For his part, he said he had more sympathy for Lang’s congregation than for Lang himself.

Parker worried Lang hadn’t relied enough on God — or that he hadn’t helped his people rely more on God and less on themselves.

“I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me,” said Parker, adding that without God’s help, the job of a pastor is impossible.

The Rev. Kerri Parker, executive director of the Wisconsin Council of Churches, said Lang’s essay had led to some helpful conversations about the struggles clergy face. Some of those clergy, she said, have a complicated relationship with the church.

“If they were on a dating app with the church, they would say they are not a thing,” she said. “But they are not, ‘not a thing.’ But they would not necessarily tell someone they are fully an item.”

She said clergy are tempted to take everything on themselves — and don’t rely on either God or their colleagues. That’s despite most clergy taking ordination vows that remind them that everything does not depend on them.

Parker said that no amount of self-care or great planning and new ideas can overcome the challenges churches face.

“We are used to holding everything together because we don’t know what else to do,” she said. “When it all goes to heck, it just goes.”

She said Lang’s essay was a gut check for pastors. Parker added that a colleague put it this way: “When we try and bear the burdens of ministry without turning them over to God, we are doomed to failure.”

For Lang, things are more complicated. He admits to being a perfectionist — memorizing his sermons, trying to make everything at church run perfectly — and trying to help his congregation follow the teachings of Jesus in the modern world.

He also says he had doubts about many of the traditional teachings of the Christian faith — such as the resurrection of Jesus or the virgin birth — and whether Jesus was the only way to find salvation. He said that he thought by modernizing theology and speaking to people in an engaging, down-to-earth manner, he could help draw people outside the church into the faith.

That didn’t work the way he hoped. Even those who were interested in his ideas found it hard to connect to a traditional congregation. COVID-19 also wrecked many of the plans the church had for the future.

Lang said he also recognized that after a decade, the church needed new leadership.

“They need someone else with new ideas to take them in a new direction,” he said.

Still, leaving was hard, something that was evident in his last sermon, which was filled with laughter and tears and a sense of genuine affection between a pastor and his flock.

Lang joked about his own failings and paid tribute to congregation members who went above and beyond the call of duty. He also thanked them for taking a chance on him as a young pastor.

Perhaps the most moving moment of the sermon came as Lang described the fraught relationship he’d had with his mother growing up. He said she was often critical, telling him he was not good enough, while Lang admitted judging his mother’s shortcomings.

While in college, Lang said one of his mentors challenged him to live out the teachings of Jesus — and to love her even though he saw her as an enemy. That changed everything, he said, recounting the story with tears in his eyes.

“If you embrace Jesus’ teaching — and that kind of unconditional love — you can revolutionize the world,” he said.

When he left, Lang’s congregation gave him a piece of Kintsugi art — made from broken pottery that had been mended with gold. That kind of pottery was a metaphor for his life, he said, that despite the struggles and his own failings, there is still beauty.

He said he remains skeptical about the future of institutional Christianity. But he is hopeful about the congregation he left behind.

In his last sermon, Lang urged the congregation to stay committed to the work they have been doing, despite the change in leadership. The church is always bigger than the pastor, he told them.

Then he gave thanks.

“You all have conveyed God’s unconditional love to me, more profoundly than just about anything in my life,” he said.