(RNS) — Depending on the week, when the Rev. Adriene Thorne steps up to the prominent pulpit of New York’s Riverside Church, she invites people to hum, stretch, or roll their shoulders before she starts her sermon.

“We’re creating space in our bodies, but also space in our spirit, to receive the message for the day,” she explained in an interview Wednesday (Sept. 20), days after her installation service. “Sometimes the stories in the Bible are traumatic. They are brothers fighting each other. And so creating some room and settling ourselves to receive that is really helpful for the message that I’m going to bring.”

The senior minister knows about the spiritual as well as the physical. Years before pursuing her call to ministry, she danced with the Rockettes five miles away at Radio City Music Hall.

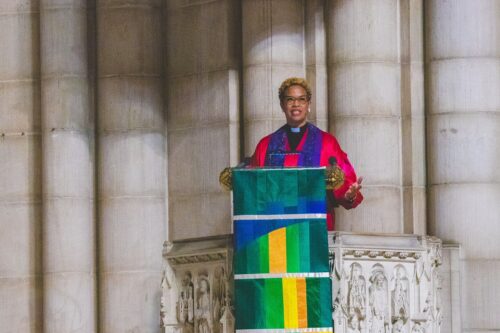

The Rev. Adriene Thorne speaks after being installed as senior minister of Riverside Church in New York, Sunday, Sept. 17, 2023. Photo courtesy Riverside Church

Her journey to the pulpit at the renowned neo-Gothic church, where leading preachers such as Harry Emerson Fosdick, William Sloane Coffin Jr., and James Forbes Jr. made their mark, has also been unconventional. Thorne, 56, was raised Catholic, ordained in the Reformed Church in America, and transferred her affiliation to the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) when she began leading the First Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn in 2016.

She said her responsibilities at Riverside, where she has been the pastor for nearly a year, are “bigger in every way imaginable: big building, big legacy, big budget” — $14 million — but that the church is facing the same challenges as other churches.

The cavernous building that once hosted 1,900 attendees on Sunday mornings now draws about 400 in person and a similar number online. She and her pastoral team aim to “reimagine the church for the 21st century” with creativity and improvisation.

“How do we care for people who consider themselves a part of our community in New York City, but they live in California?” she asked. “Do we go to California to do hospital visits? I don’t know. So we’re going to have to figure that out.”

Thorne talked with Religion News Service about what it means to be the church’s first African American senior minister, why she left the Rockettes behind, and what’s next for her progressive church.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Your installation service was held on Sunday. What did it feel like to reach this point as Riverside’s first African American woman leader?

It was stunning and surreal and incredibly joyful. It was just great to share that with my mom and my daughter and other family.

You are following in the footsteps of peace activist William Sloane Coffin Jr., James A. Forbes Jr., the church’s first Black minister, Amy Butler, the church’s first woman pastor. How will you build on what they did at Riverside?

I think all of the ministers, but I would say Dr. Forbes and Dr. Butler, in particular being in the most recent time, are trying to set a bigger table. And I think that is something that I am definitely building on. So we are welcoming people of different races and colors and ethnic backgrounds, but I think also gender expressions, identities.

Many African Americans, including African American women, have moved into prominent roles in the pulpit and in seminaries. What does that say to you?

I often like to say that I came to Riverside the same year that the Honorable Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson ascended to the Supreme Court. So I kind of think of her as my patron saint. I think a lot about what she had to endure in her confirmation hearings and use that as fuel to fire me in the work that I do. All of us, women who are ascending to these roles, I’m interested in their stories because I think we share similar fiery stories as Judge Ketanji and can use that to fuel ourselves.

In your letter to the congregation as a candidate, you cited the big challenges ahead: lack of belief and falling membership. How have you tried to address that at Riverside?

I believe that in this moment, after we have been in lockdown and have experienced tremendous political and racial discord and divide, that people are hungry for what the church has to offer. I think wanting to offer spaces where people can connect and reconnect has been at the center of addressing falling membership. We’ll start, the first Sunday in October, an opportunity to practice Sabbath. Churches can be some of the busiest places on Sunday morning, and to be able to invite the congregation to sit and pause after worship to have a cup of coffee, have lunch together and sit with their pastors is something that we’re instituting. We’re also dealing with an epidemic of loneliness, not only in New York City, but around the world. I think that’s going to make a difference in who we are as a community and how we grow together with each other and in our relationship with God.

At your previous church, you co-founded the Brooklyn Heights Community Fridge. How does it work? And will there be one at Riverside someday?

There are more than 100 community fridges in New York City in a variety of neighborhoods. You just need to find a business, a church, a school who’s willing to provide the electricity and then you need a donated fridge. What neighbors do is they help neighbors who are hungry. So if you have something to share, you leave it. If you need something, you take it. Might Riverside have that? I think it could be a useful thing.

How does someone go from being a Rockette to senior minister of Riverside?

I think a lot of it was timing for me. I became a Rockette at Radio City in the year 2000. And 9/11 happened in 2001. I was in my late 30s at that time, and I always thought I would leave dance to do something else at some point. I think 9/11 was a catalyst. I was in an audition, doing a dance sequence, and I remember looking at myself in the mirror doing this dance move called the flea hop. And I just thought to myself, “You look like such a fool.” While dance and the arts, I think, do heal the world and bring so much gift to the world, I felt that my call was shifting. I thought I was going to get a master’s in literature. But I kept feeling this tug to go to seminary.

You danced as well with the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Have you incorporated dance into Riverside’s activities?

I love bringing dancers that I know into the space. We had some at my installation on Sunday. What I think is so powerful, about the arts, in worship, particularly dance: There are ways that we touch the holy that can’t be spoken. Even though in my tradition we center the spoken word, we center the sermon, what people remember when you talk to them years later, is that dance that they saw, that musical piece that they heard, that ritual of receiving Communion. That is what drops into the heart of people and drops them into the heart of God, faster than any sermon that I deliver.

Every Sunday you step into a pulpit where Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez and Nelson Mandela have spoken. Does that ever get old or does it get just overwhelming sometimes?

Like stepping on a stage, it never gets old. And that’s where there’s some similarity, I think, between worship and performing. There’s a high level of oratory. We’re costumed in a robe. There’s an audience, the congregation, but it’s a very naked experience as opposed to being onstage where the audience is in darkness. Getting into that pulpit every Sunday morning is a very naked experience. I’m talking about our life together, my life, the life of our city, the life of our congregation. I don’t think too much about who has stood in the pulpit because, as you said, I think if that were in my head, it would be overwhelming. It would be very hard to put two words together. But I do think of the weightiness of what it means to step into that pulpit. But any pulpit, any time you are standing to say, “Thus saith the Lord,” that’s a weighty proposition.