(RNS) — Ten minutes into a new documentary on the battle for women’s ordination in the Episcopal Church, a short archival clip shows the first time women were seated as full voting members in the denomination’s House of Deputies.

But even as women took that minor step forward, they were introduced by a male priest who described the women deputies as “bringing us something the House has needed desperately for a long time — some beauty.”

Such were the belittling attitudes toward women four years before a group of 11 seminary-educated female deacons challenged their church to accept them as priests in 1974.

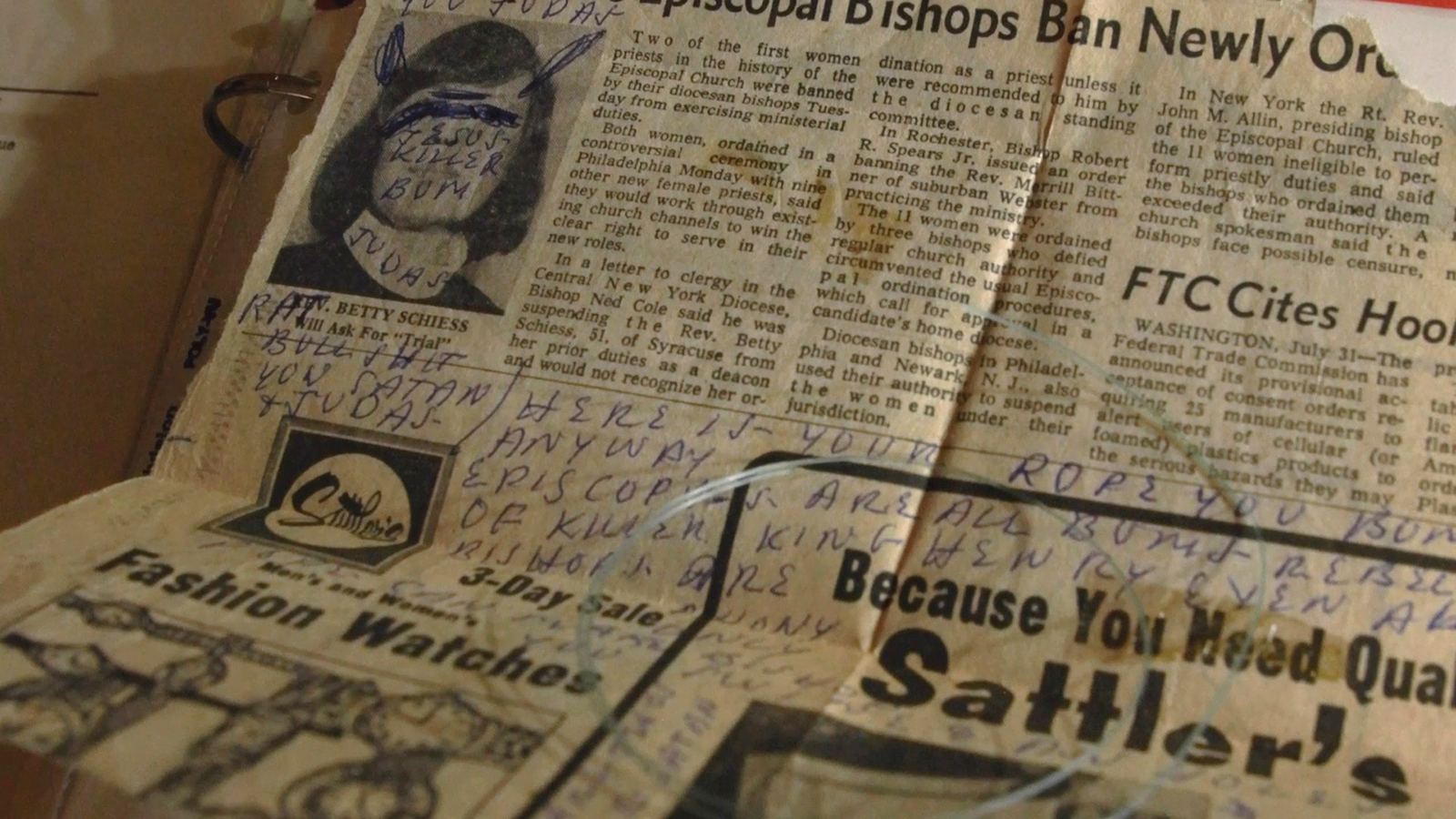

“The Philadelphia Eleven,” a new documentary dozens of churches are now screening across the country, depicts the buildup toward the so-called irregular ordination at which three bishops (with a fourth observing) ordained 11 women as priests without the denomination’s approval. The ordination — often described as an act of disobedience — caused deep divisions in the church. The women were vilified in the media and in personal attacks. But they also paved a path toward the full embrace of women priests by the denomination two years later, in 1976.

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of that irregular ordination and the documentary casts a fresh light on that momentous time and on the methods used to achieve it.

Six of the 11 women ordained — all white — are still living, and their eloquent testimonies that they are equal to men form the essence of the documentary. In contrast, male priests and bishops appear in archival images railing against the idea of women priests, intoning that “priesthood implies fatherhood,” and as one priest insists, “We cannot have a female rooster.”

A still from “The Philadelphia Eleven” documentary. (Courtesy image)

Old-fashioned as those comments may sound, their sentiment is still widespread in Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, where women have yet to be ordained, as well as in the Southern Baptist Convention, where women may not serve as pastors.

The documentary also comes at a time when gender equality has stalled as state legislatures restrict abortion and legislate against trans youth.

“We’re in a space where women’s rights are starting to get rolled back, and to understand the stories of the women who come before us and the shoulders we stand on is the only way we move forward,” said Margo Guernsey, the film’s director and producer.

An independent, Massachusetts-based filmmaker, Guernsey said she never heard about the Philadelphia 11 until she had a phone conversation with one of its leaders, the Rev. Carter Heyward, and came away wanting to know more.

Guernsey set about filling in that gap in her knowledge. It turned into an eight-year odyssey that included interviews with the surviving Philadelphia 11 and the people around them, deep dives into reams of archival footage and, most difficult of all, raising money for the documentary, underwritten by 1,200 individuals.

Several of the Philadelphia 11 are now attending the church screenings. A wider distribution of the documentary is expected in late 2024.

Heyward is featured prominently in the documentary. She and Emily Hewitt were among the group’s leaders. In the early 1970s, both were studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. They were joined by Suzanne Hiatt, who was working as a social justice organizer at Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia.

The Episcopal Church had no rule forbidding female priests, but ordaining them just wasn’t done. After several attempts to allow women’s ordination failed at General Conference, the three began to plot to shake up the status quo.

“It was not until the convention in Louisville in 1973 rejected women’s ordination by even a greater margin than the 1970 convention in Houston that we realized something needed to be done to sort of crack this thing open,” Heyward, now 79, told Religion News Service.

Times were changing. The Equal Rights Amendment was overwhelmingly approved by both houses of Congress in 1972. The Civil Rights Movement for African Americans had a profound influence on the women. (The documentary includes a powerful interview with Barbara Harris, the first woman and the first Black woman to be consecrated a bishop in the Episcopal Church.) In addition, other denominations had already begun ordaining women, including the United Methodist Church and parts of the Presbyterian Church (USA); the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America first ordained a woman in 1970.

Hiatt eventually convinced the Rev. Paul Washington, a Black priest, to conduct an ordination for women at Church of the Advocate and recruited four bishops who were willing to take part.

Word of the July 1974 ordination leaked to the press and all the TV networks lined up to cover it. The church, which seats 1,000, was packed. After the three-hour ceremony, Episcopal bishops were called to an emergency meeting at O’Hare Airport in Chicago, where the ordination was ruled “invalid” and the women forbidden from performing the sacraments.

They did so anyway — celebrating the Eucharist at the Riverside Church in New York City, which is not affiliated with the Episcopal Church. Later they were invited to celebrate the Eucharist at two Episcopal churches. (Both male priests were put on church trial and charged with violating the church’s constitution and canons for allowing it.)

But even after the General Convention in 1976 voted to allow women’s ordination and “regularized” the ordinations of the Philadelphia 11, it was hard for the women to find jobs leading churches. The Philadelphia 11 went on to teach in seminary, with some, such as Heyward, becoming theologians. Others served as chaplains.

“The Philadelphia Eleven” is a new documentary about women’s ordination in the Episcopal Church. (Courtesy image)

The Rev. Nancy Wittig spent the first 10 years after her ordination as a “supply priest,” filling in for vacationing clergy. She was eventually called to serve two small churches — one in New Jersey and one in Pennsylvania. Later in Ohio, where she now lives, she worked as an assistant to a rector in a suburb of Cleveland.

In a phone interview, Wittig noted with pride that her Ohio diocese just elected a woman bishop and the Diocese of Southern Ohio has also called a woman to be its bishop. “It’s happening,” she said. “It’s right and it’s good.”

Halfway through the documentary it becomes clear that five of the Philadelphia 11 were also gay.

Heyward said only she and her friend Emily Hewitt were out at the time of their ordination. Others, such as Wittig, came out much later.

In some ways, their sexual identities were linked to their defiance of prevailing norms.

“When you have been defined outside the box of what is considered the norm, that is, the male priesthood, you’re already an outsider,” Heyward said, suggesting it became easier to also embrace their sexual identity.

“The Philadelphia Eleven” (official trailer) from Time Travel Productions LLC on Vimeo.

Heyward has also gone further in her theological understanding. After retiring from the Episcopal Divinity School where she taught, she returned to the mountains of North Carolina where she grew up and bought some land for a therapeutic horseback riding center called Free Rein. She still considers herself an Episcopalian but said she has a hard time connecting to the Book of Common Prayer’s gendered language. She now attends a Unitarian Universalist church.

“I sometimes go the Episcopal church but usually when they’re having special services that are inclusive,” Hewyard said. “By that I mean, services in which God is celebrated as male and female, as mother, father, spirit-lover. I worship, in places where that is lifted up.”