(RNS) — Ask a college chaplain, and you’ll hear a story behind the pro-Palestinian protests on American college campuses that is more complicated, and in some ways less dire, than what you’re seeing on television or in your news app.

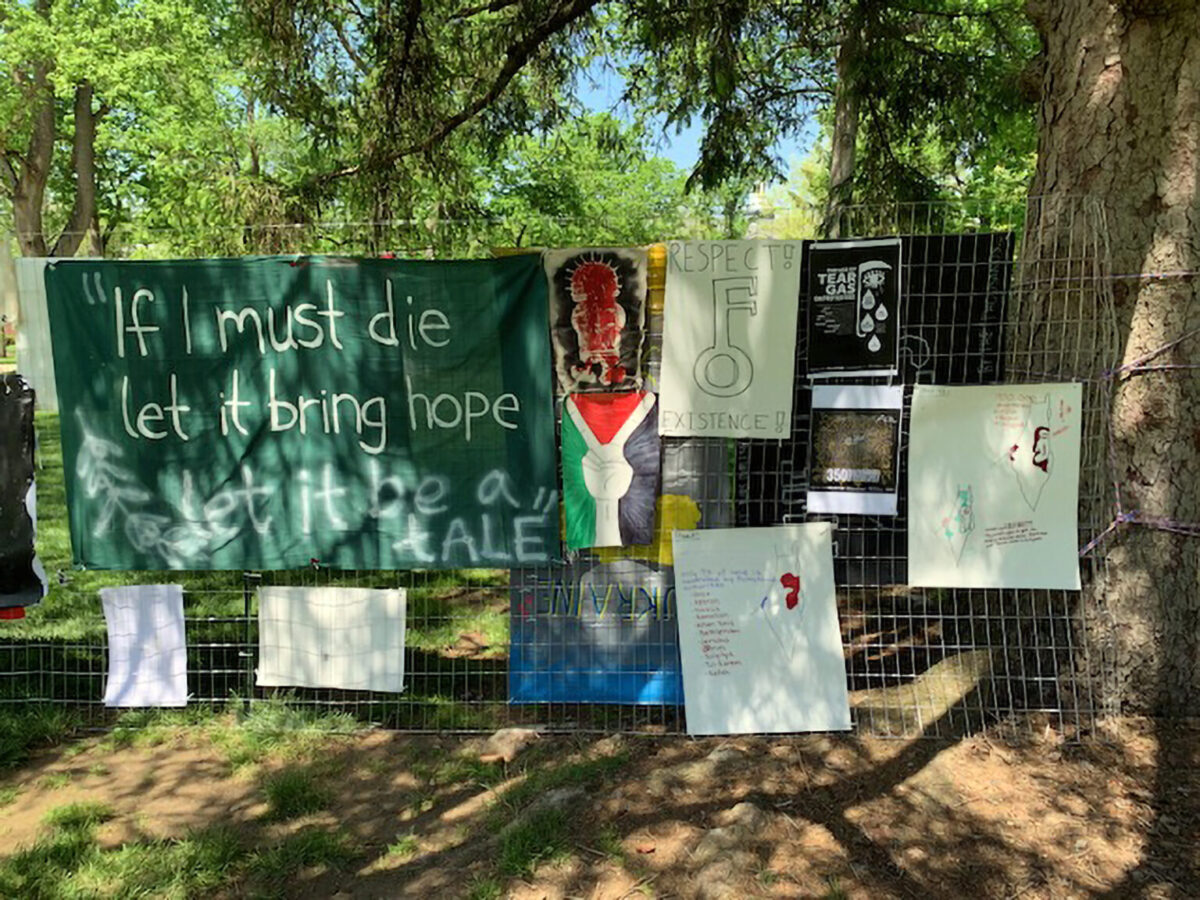

Posters on campus at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. (Photo courtesy Mimi Holland)

Media accounts of the pro-Palestinian protests and counterprotests have focused on unwelcome encampments, fights between rival groups, and arrests by police. But the conflict in Israel and Gaza, and the profound issues it raises, some campus spiritual leaders say, have done what colleges and universities are meant to do: prompted them to reflect on what it means to be moral agents and to assess their own diverse faiths.

Whether students participated in encampments, prayer vigils, Shabbat rituals, or supporting other students, they were growing spiritually and learning how to claim their own place in history, the chaplains said.

Janet Cooper Nelson, a United Church of Christ minister who has long headed Brown University’s chaplaincy team, said the students at the university where encampments ended after officials agreed to vote on student demands this fall represented a wide spectrum of beliefs.

Usama Malik. (Courtesy photo)

At the large public campus of the University of Texas at Austin, Muslim students have told Usama Malik, a chaplain with Muslim Space, a community-building organization in Austin, that their trust in university administrators and public officials has been damaged by aggressive attempts to clear the encampments, even as solidarity among students of different religions has increased in past weeks, often with support from local pastors, faculty and even parents.

Having seen art-making workshops, a teach-in, a Shabbat service, and an interfaith prayer vigil in recent days, said Malik, “you’re really seeing a variety of things that often get missed in the way the news media has been covering the story.” The events, often student-led, are “diverse, eclectic and very moving.”

At Brown, said Cooper Nelson, students have become more involved in campus politics and their own faith issues. Those she has encountered “are prayerful, spiritually formed on the inside,” she said. “You see the students weighing the ideas and their decisions about engaging those ideas or moving them forward, very much based on how they understand what it is to live a life that’s grounded spiritually.”

Sr. Jenn Schaaf, a Dominican sister and assistant chaplain at Yale University’s St. Thomas More Chapel & Center, said the war for many students is by no means an abstraction. “Like the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, we have students who have relatives in Israel and Palestine. They are worried about people they know,” she wrote in an email.

“I’m grateful that our students are engaged in the religious and political sphere,” she added. “I’m also grateful that they are safe.”

Overall, the chaplains who spoke to RNS seem united in admiration for their students’ capacity to form their own opinions, make moral judgments, and embrace the moment, as turbulent as it is.

Indeed, Cooper Nelson’s colleague at Brown, Reconstructionist Rabbi Jason Klein, said that while Jewish students have welcomed the chance to connect the protests to Jewish values, spirituality, and practice, they don’t want to be told by outsiders what to believe about the issues at the heart of the protests.

The Rev. Janet Cooper Nelson, left, and Rabbi Jason Klein are chaplains at Brown University. (Courtesy photos)

Cooper Nelson doesn’t consider it the chaplain’s role to teach as much as facilitate students’ takeaways. “It’s not my job to tell them what to do. It is my job to listen carefully and to try and hold up a mirror of what I hear them weighing and measuring what they are putting out there as the ideas that seem most important to them. I think we’re acting as friends, non-judgmental sounding boards.”

The Rev. Roger Landry, a chaplain at Columbia’s Thomas Merton Institute for Catholic Life, said he has attempted to focus students on helping one another. “There’s a temptation to think that a campus demonstration on a New York campus is going to have a major impact on a 76-year-old, seemingly intractable dispute in the Middle East. I’ve urged them to be far more practical by doing what we Catholics do, turning to prayer and to personal care,” he wrote in an email, adding that this “includes reaching out to Jewish and Palestinian friends to ask how they can support them.”

The majority of Catholics at Columbia are hard working students who prioritize sanctifying their studies, and despite their many concerns over what has happened in the Middle East before, on, and after Oct. 7, they aren’t happy that the toxins of that region have been brought onto their campus,” he added.

At smaller institutions, the war has also had an outsize effect, and the role of the chaplain has sometimes been more personal than at larger urban schools. At Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, students and faculty held a teach-in and a prayer vigil last fall and called for a cease-fire, prompted by students who had gone to Israel and the West Bank over the summer. After more student-led action this spring, the university administration joined them in urging the U.S. government to work for a cease-fire.

The Rev. Brian Martin Burkholder, the Mennonite chaplain, said he has tried to be present with the students who were on the trip who “felt compelled to speak out for those who were losing their voice and homes and land due to Israeli attacks and control,“ he said. “I’ve checked in on occasion to see how they are doing and offer a space for reflection on their experiences. I wanted them to know they were seen, supported and valued.”

Brian Martin Burkholder. (Photo by Macson McGuigan)

“Our Anabaptist Mennonite faith tradition informs supporting one another in community as well as giving and receiving counsel,” said Burkholder.

At Indiana’s Earlham College, historically Quaker but now very diverse ethnically, economically, and across faith traditions, students have focused on how they can support each other, rather than being combative, said the coordinator of Quaker and religious life, Mimi Holland. As at Yale and many other institutions, there are students who have family members, both in Israel and in Gaza, she said.

“I think there is something about the culture that is rooted in the Quaker way that promotes more thoughtful responses. The message of justice, bridge building, how we are all interconnected, not just as human beings but as the entire world and environment we live in … that’s very much part of our culture.

“Our students are amazing. I see young people really putting the best part of their faith forward and acting on what their faith causes them to do in kind, loving, peaceful justice-seeking ways,” said Holland. “I’m just gobsmacked by how caring and thoughtful they are.”