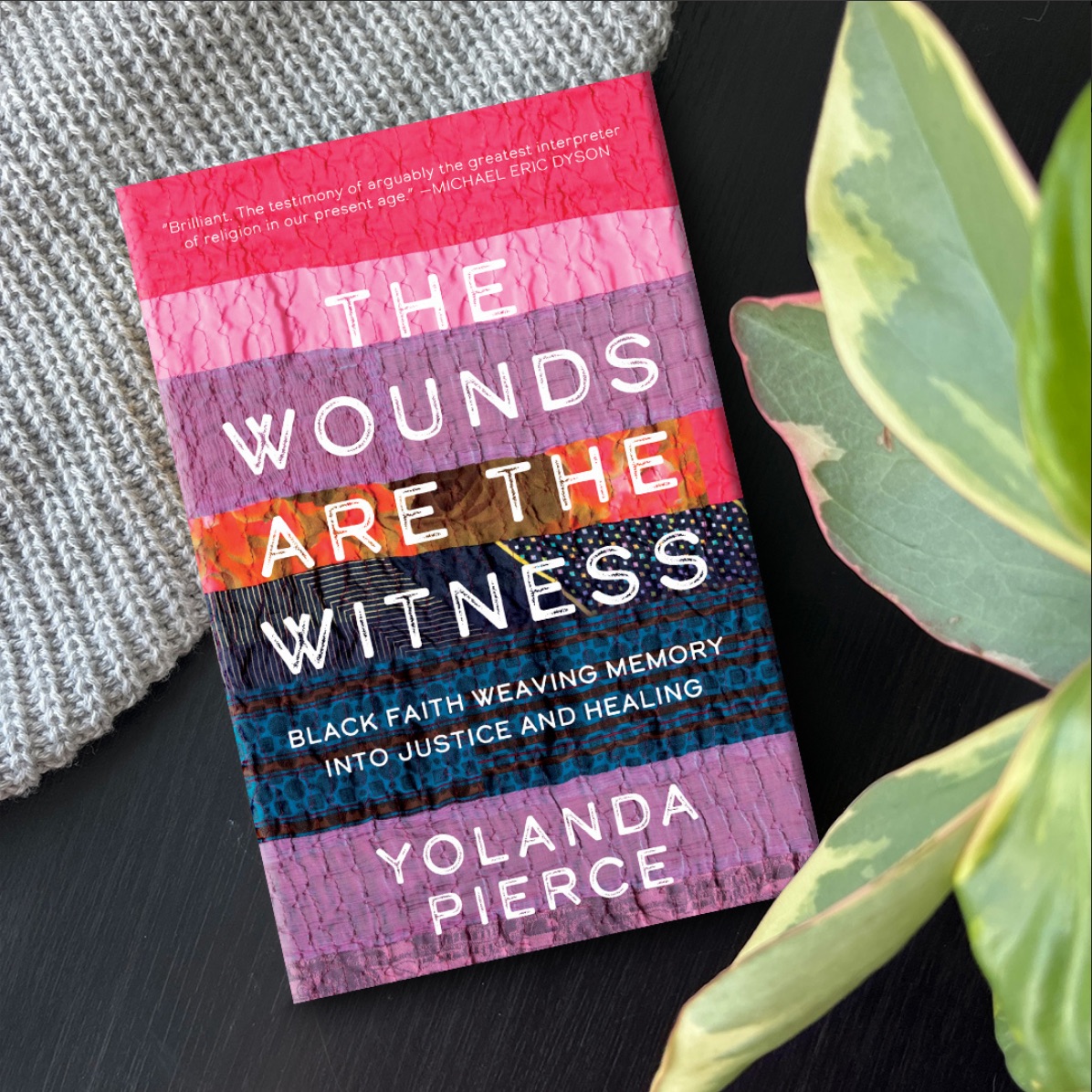

THE WOUNDS ARE THE WITNESS: Black Faith Weaving Memory into Justice and Healing. By Yolanda Pierce. Minneapolis, MN: Broadleaf Books, 2025. 196 pages.

We are witnessing a backlash against Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion that is leading, under the Trump Administration, to the complete rollback of DEI programs in the federal government and in numerous companies. Programs that are designed to broaden the playing field are under attack, which likely means few women and people of color will be considered. While we’re told that hiring decisions should be made based on merit, more likely this has to do with making sure that white men can once again get to the front of the line. I say this as a white male. Fortunately, if we’re willing to listen, there are important responses that bear witness to justice, especially for those who have historically been excluded.

Robert D. Cornwall

The Wounds Are the Witness: Black Faith Weaving Memory into Justice and Healing by Yolanda Pierce offers one of those needed reminders that speak of wounds of the past and offer hope for the future. This is a powerful and beautifully written meditation that will touch hearts and offer hope for healing even as it addresses the wounds that so many have experienced, wounds that must not be forgotten, especially in this moment.

Pierce is dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School and is a scholar of African American religious history. She draws upon her own experiences in the black church, more specifically the Holiness-Pentecostal tradition, and as a womanist theologian, to speak of the wounds she and others have experienced as well as the faith of the black church that offers a path to justice and healing. She seeks to bear witness to the wounds experienced and the possibility of healing. She brings into the conversation her experience of presiding at the Lord’s Table, a place and experience that calls for people to remember. She writes that “we cannot remember the healing justice of God without remembering the wounds of the crucified. This is the task of every Christian believer as well as our greatest eschatological hope” (p. 7). She reminds us that all are welcome “in the radical belief that only God’s justice quenches our thirst, heals our spirits, and renews our hearts” (p. 8).

Pierce offers us ten chapters in which she weaves stories of wounds, justice, and healing, bringing into the conversation scripture read through the lens of the black faith experience. The first chapter is titled “Carrying the Bones: Wounded Remains.” She shares that bones carry memories, these include the bones of her enslaved ancestors. They speak of experiences of “brutal labor, bone-breaking injuries, and starvation” (p. 11). She pairs this discovery with biblical stories of the Israelites carrying home the bones of Joseph, doing so with great care, as well as Ezekiel’s message about the valley of dry bones. She writes that her ability to hope and dream “rests solely on my belief that death does not have the final say. We carry the bones, but they do not define us.” Instead, they carry memories that offer healing for the path forward (pp. 24-25).

We move on to a chapter titled “Won’t Break My Soul: The Wounds of Shame” (Chapter 2). In this chapter, Pierce begins with the story of an incident of police brutality committed against a young black girl at a pool party that included the involvement of another white man. Pierce notes the horror and the shame that she felt as she watched this video. She asks the question of what one can do with wounds that involve shame and humiliation, as that young girl experienced. In this chapter, she brings into the conversation the story of Miriam, the sister of Moses, who was cursed and humiliated after she and Aaron opposed Moses’ marriage. Yet there is redemption here because the people did not move forward until Miriam was brought back from her exile. The lesson she learned from the story of the young girl and Miriam: “There is no progress unless the wounded among us—those broken in heart and bruised in spirit — have space to tell their stories and share their burdens. Justice is only possible if the ones cast outside of the camp, the city, or the church are lovingly brought back into a changed and transformed community” (p. 44).

As we move forward, Pierce speaks of “Down South: Healers with Wounds” (Chapter 3). In this chapter, Pierce talks about the tradition of Black youth from the Great Migration being sent south during the summers to experience life there. She speaks here of the traditions of folk medicine and its aid to healing. She writes that we should seek the healers when we want to see God at work. Chapter 4 is titled “Lay Aside Every Weight: The Heaviness of Wounds.” Here she tells how enslaved Africans envisioned flying away from their bondage. We know the image from the spiritual “I’ll Fly Away,” but the vision here is not the afterlife but the stories of slaves simply flying away to Africa, escaping their bondage. The message here is one of freedom which begins with surrendering to God’s presence.

In Chapter 5 Pierce broadens out the conversation with a chapter titled “The Soil Is Exhausted and So Am I: The Wounds of Creation.” Here she notes that slavery not only wounded enslaved people but creation itself, as the soil the slaves worked would end up exhausted, requiring that new lands be found to farm. Here she points us to the experience of Ash Wednesday, an event where people are marked with ash and reminded that they are dust and to dust they shall return. For the wounds of creation to be healed, there needs to be environmental justice. It is, she writes, a theological issue but also a racial issue for the way we treat the land, and the people who work the land are intertwined.

Pierce next writes of “Trust Betrayed: Wounded in the House of a Friend” (Chapter 6). She tells of a white colleague who simply did not believe her story of how she was treated and perceived in the classroom. He believed everyone was treated equally, but such was not the case. This leads to other stories of Black people facing discrimination. These stories include the story of Black World War II veterans, including her father, who were excluded from benefiting from the GI Bill that enabled so many white veterans to better themselves for the future through education and housing. This has left many in the Black community impoverished because they could not share in generational wealth. Writing here from a womanist perspective, Pierce takes note of Jesus’ own experience of betrayal. Acknowledging this possibility is a foundation for healing.

In the chapter “Innocence Is the Crime: The Wounds of Inhospitable Places” (Chapter 7), Pierce tells of her experiences in the Holy Land and her interactions with the people and places there. She raises the question of how place impacts us, and whether there are hospitable responses to our presence. In this chapter, Pierce invites us to consider our own involvement in the sins of our context. She speaks here of the penitent thief who hung next to Jesus and acknowledged he deserved his condemnation and the forgiveness that came to him. She writes that we “cannot rest in a place of racial innocence.” We can’t ignore the crimes and violations that exist in our context, but we can recognize that God is calling forth people from these contexts to speak truth to power (p. 130).

The next chapter draws from the story of Thomas’ encounter with the risen Christ. It is titled “The Risen One: Until I Touch the Wounds” (Chapter 8). She includes in this chapter about resurrection a litany she wrote after the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. It is titled “A Litany for Those Not Ready for Healing.” This is a reminder that we should not rush forgiveness or speak of reconciliation without some form of reparations. She writes, with the story of Thomas in mind, that “If we are to love Jesus, we have to love the man with the still-healing wounds and not just the conquering hero” (p. 144). Thus, if healing is to occur, it will likely take time. It also requires love.

Yolanda Pierce is a product of the Holiness-Pentecostal tradition, so a chapter titled “Tongues of Fire” is appropriate. Subtitled “The Heart’s Language and Wounded Breath” (Chapter 9). She points out that she speaks Black Church, at least in private devotions and when she is with the saints. This language is focused on the justice of God. As for Pentecost, she envisions it as entailing “the radical inclusivity of the table where all are welcome to sit and eat. Pentecost is also about the breath of God, about restoring life to the wounded and broken” (p. 160). That is something that is quite needed at this time when division and cruelty seem to be the language of religion as well as politics.

Finally, we come to Chapter 10, “Just Keep on Living: The Wounds of Disconnection.” She speaks here of the process of deconstructing faith and then rebuilding it. She points out that faith deconstruction often involves “physical and social disconnection from the community,” which produces its own wounds. She suggests that rituals serve as part of the process of rebuilding and reconnecting. Ultimately, the question is where do we find community as we deal with the wounds we experience? The answer includes simply keeping on living, because “trouble don’t last always and God will never leave you or forsake you” (p. 179). Thus, finding that place where we can tend to each other’s wounds is important to the journey to healing.

In the conclusion to The Wounds Are the Witness, a chapter titled “Dangerous Memories,” Pierce takes us to the story of Nehemiah the cupbearer to Artaxerxes who is sent to Jerusalem to rebuild the walls of the city. She suggests that he engaged in the work of “prophetic retrieval,” a work she envisions engaging in herself. She envisions retrieving the memories of her people so that she can participate in the healing process moving forward. I’m reminded here of the efforts underway to rewrite history so as to erase the realities of Black Americans and other persons of color, as well as women. We’re being told that we need to embrace a sanitized patriotic history that whitewashes the realities of the past. Pierce offers us a different path by bearing witness to the wounds of the past so that healing might be experienced.

Yolanda Pierce’s The Wounds Are the Witness: Black Faith Weaving Memory into Justice and Healing is a book that speaks to this particular moment when resistance to oppression is required. She has borne witness to the stories of woundedness, woven together with a faith deeply rooted in the Black church experience, such that there is the possibility of healing. But it will not come without a struggle. However, as Pierce continually reminds us, God is present in the midst of this. This is a powerful book that speaks to the moment, even if you are not Black or part of the Black Church tradition, she roots her vision in her faith in Jesus.

This review originally appeared on BobCornwall.com.

Robert D. Cornwall is an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Now retired from his ministry at Central Woodward Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) of Troy, Michigan, he serves as Minister-at-Large in Troy. He holds a Ph.D. in Historical Theology from Fuller Theological Seminary and is the author of numerous books including his latest “Second Thoughts about the Second Coming: Understanding the End Times, Our Future, and Christian Hope” coauthored with Ronald J. Allen. His blog Ponderings on a Faith Journey can be found at www.bobcornwall.com.