NOTE: This piece was originally published at our Substack newsletter A Public Witness.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents last month arrested and detained a carpenter named Jesus. No, not that Jesus the carpenter — although in the Matthew 25 sense it is doing unto that Jesus.

Jesus Teran came to the U.S. from Venezuela in 2021. He showed up to all of his immigration hearings, has no criminal record, worked for a carpenter’s union, and was active in a local Catholic church. When he went for what was supposed to be a regular check-in at the ICE office in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on July 8, he was abruptly detained despite following all of the rules. Now, members of his Catholic church are advocating for his release and supporting his wife and two children.

“Jesus is not someone who should be subjected to this undignified experience that he’s going through,” said Rev. Jay Donahue, senior parochial vicar at St. Oscar Romero Parish. “It’s a shame the way they are treating him; it is inhumane. It’s been inspiring to see the community rally around Jesus and to recognize what he means to our community.”

“Deporting Jesus doesn’t make this a safer place,” added Chris McAneny, director of housing for a nonprofit that Jesus volunteered with. “It’s creating havoc and fear. He was contributing to his community, raising his family, paying taxes, and now he’s in a detention facility separated from his family.”

The family came to the U.S. seeking asylum after violent threats. That legal process is ongoing. But Jesus has been locked in a sleeping area with about 80 other detainees, separated from family members who are retraumatized and worried he will be deported back to Venezuela or some other place where he would be neither free nor safe.

While inhumanely detaining a carpenter named Jesus is a bit on the nose for an imperial power, Jesus the carpenter’s story is far from unique in this alarming moment. Numerous congregations across the country have seen government agents snatch up law-abiding, active members of their churches. Among those arrested and detained have been several pastors.

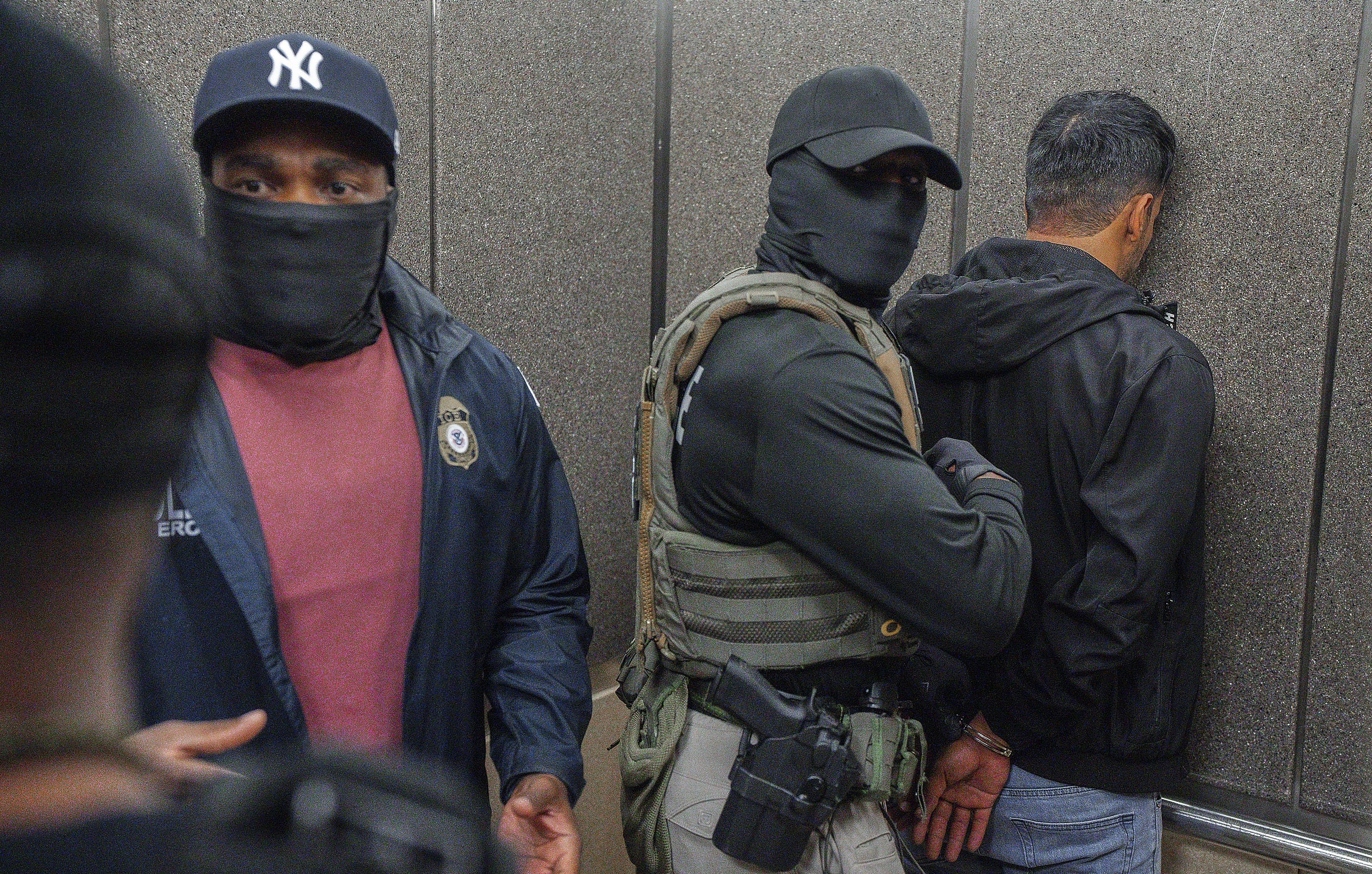

Masked men presumed to be ICE agents detain a man after he left an immigration courtroom in New York City on June 17, 2025. (Olga Fedorova/Associated Press)

Despite administration talking points that emphasize the apprehension of violent menaces to society, fewer than 30% of those being held in ICE detention centers have a criminal record. And most of those who do have a past conviction are for minor offenses like a traffic violation.

Instead, many have been detained at immigration hearings. Being arrested is their reward for trying to follow the rules. Others have been arrested at their place of employment, where their only offense is a commitment to working hard and providing for their families. And a few have been picked up on church property or on their way to worship, showing the growing threat to religious liberty rights under the Trump administration.

Coverage of these cases by various news outlets shows the importance of local journalism in telling the stories of those being arrested, detained, and deported. By themselves, each story can seem like an exception or an outlier. Taken together, they show a disturbing trend and urgent moral problem. So this issue of A Public Witness looks behind the unmarked cars to see the chilling impact of ICE raids on pastors, churches, and communities.

Deporting the Lord’s People

Until his arrest by immigration agents last month, Pastor Daniel Fuentes Espinal had led a church on the Eastern Shore of Maryland since 2015. According to his daughter, he has no criminal record and has been trying to navigate the citizenship process. She also reported, “He preached to [the ICE agents] all the way to [the holding center].”

In Florida, Rev. Maurilio Ambrocio was deported back to his home country of Guatemala in early July. His absence has devastated both his biological family — he’s the father of five — and his church family. As his daughter told a Tampa TV station, “Many more people need him [in the United States], the church, friends, family. They all need him back there.”

In California, Pastor Gennediy Glushchuk was arrested when he went in for his annual immigration status meeting in Los Angeles in June. He has been detained out of state, away from his wife and two daughters. And he missed the birth of his son.

In other places, it’s church leaders who have suddenly disappeared. In one jarring example from Massachusetts, Daniel Flores-Martinez was pulled from his vehicle while on the way to church with his family on Mother’s Day.

“My children watched as their father was physically attacked, treated like an animal, and ripped away from us,” his wife Kenia Guerrero told WBUR. “They have so many questions, but I don’t have the answers. Why would the government tear our family apart like this? No mother should have to explain this kind of cruelty to her children.”

Last week, Pastor Joanna Lawrence Shank and some members from First Mennonite Church in San Francisco, California, accompanied a congregant to an immigration hearing. As they left the room, agents suddenly surrounded the young man and hauled him off as his fellow Mennonites sang the hymn, “Lord, Listen to Your Children Praying.”

Yesterday, ICE finally released a Purdue University student who is also the daughter of an Episcopal priest after arresting her last week during what was supposed to be a routine visa hearing. Lawyers for the Episcopal Diocese in New York that worked to secure her release disputed Homeland Security claims and insisted that her current visa doesn’t even expire until December.

Two Christian chaplains at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital were fired after they showed support for a fellow chaplain who was arrested by immigration agents. Imam Ayman Soliman now faces deportation after the government revoked his asylum status, which was granted in 2018 after he fled torture in Egypt. And a pastor merely attempting to observe arrests inside an immigration court building in New York was arrested.

Additionally, in Los Angeles, two Iranian Christians who were seeking asylum based on claims of religious persecution in their home country were arrested while their pastor, Ara Torosian, helplessly recorded the event and urged the masked agents to stop. The cruelty he witnessed motivated him to travel to D.C. and hold a hunger strike in front of the White House.

“When I saw that scene, it triggered something inside of me, and I thought, ‘Where am I? Am I in L.A. or in the streets of Tehran?’” Torosian explained.

A volunteer sets up an art installation displaying names and faces of people who have been detained, deported, or sent to offshore camps during ICE raids in Southern California, at Olvera Street Plaza in Los Angeles on July 3, 2025. (Damian Dovarganes/Associated Press)

Across the country there are news reports of Hispanic churches seeing significant drops in worship attendance because of the climate of fear that’s been created. And that’s getting noticed not only by President Trump’s critics, but also by his supporters.

“Thirty-five, 40% drop in Sunday attendance,” Samuel Rodriguez, president of the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference and a vocal Trump supporter, said in an interview with CBN News, which is about as far from MSNBC as Wasilla, Alaska, is from Burlington, Vermont. “Put this in perspective, close to half of the Latino evangelical church, 40% aiming towards 50, this is serious.”

That alarm at what’s transpiring reflects a dramatic shift from what Rodriguez predicted after Trump’s election.

“The mass deportations will focus on the mucho malo hombres — those that are involved in criminal activities,” he asserted to NPR in December. “I do not believe the incoming administration will be targeting a man who is working, who’s been here for 20 years, whose family was raised here and kids were born here, and has never even received a parking ticket.”

Help sustain the journalism of Word&Way by subscribing to A Public Witness!

When Sanctuaries Aren’t Safe

ICE’s tactics are not only emptying pulpits and pews, they’re also changing how ministers and congregations are doing ministry.

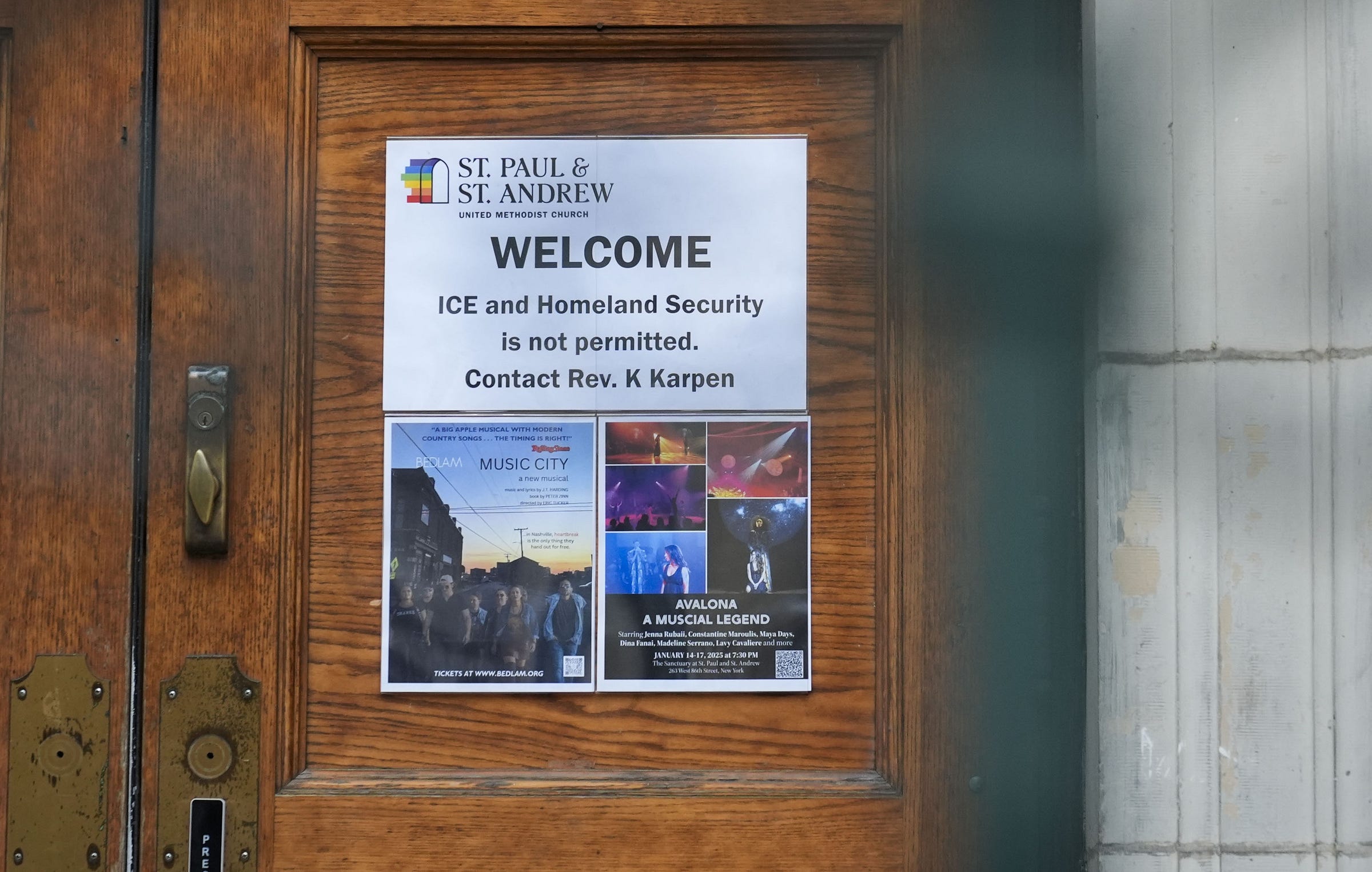

Following a change in ICE policy that allows for immigration enforcement in church sanctuaries, many congregations are preparing for the possibility of agents showing up during Sunday morning worship or weekly business hours. This involves devoting significant time to planning, education, and communication by both church staff and members.

“As a church, you need to know where your public spaces are and where your private spaces are,” Los Angeles pastor Caleb Crainer explained in a story about his church’s extensive preparations. “Because when ICE shows, they can go into any public space. But they are precluded from going into any private space without a warrant.”

Relationships between law enforcement and faith communities are also shifting. Churches are growing more skeptical of police utilizing their property out of concern they’ll become staging grounds for immigration enforcement operations. In California, a pastor who came to the aid of an immigrant being arrested on her church’s property had a gun drawn on her by the agents involved.

“It came across as essentially a final warning, to step back,” is how Tanya Lopez, pastor of Downey Memorial Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), interpreted the officer’s escalation.

Several other incidents have occurred on church property, including a parishioner arrested while doing landscaping at a Catholic church in California, a man grabbed in a church parking lot in Washington as he left Sunday worship, and a man arrested in Georgia after officials buzzed him to step outside during Sunday worship.

A sign that prohibits the entrance of ICE or Homeland Security is posted on a door at St. Paul and St. Andrew United Methodist Church in New York City on Jan. 21, 2025. (Seth Wenig/Associated Press)

On a more macro scale, policy changes by the Trump Administration are causing entire traditions and denominations to re-evaluate how they engage with the federal government in critical, but previously uncontroversial areas. Both the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Episcopal Church have chosen to end refugee resettlement programs because of changes they found unacceptable.

For Episcopal leaders, the decisive moment arrived after demands by the U.S. government that its ministries resettle White Afrikaners from South Africa, despite contested claims over their status as refugees, while the Trump Administration had effectively ended the processing of refugees from other places.

“It has been painful to watch one group of refugees, selected in a highly unusual manner, receive preferential treatment over many others who have been waiting in refugee camps or dangerous conditions for years,” Episcopal Presiding Bishop Sean Rowe detailed in a letter. “I am saddened and ashamed that many of the refugees who are being denied entrance to the United States are brave people who worked alongside our military in Iraq and Afghanistan and now face danger at home because of their service to our country. I also grieve that victims of religious persecution, including Christians, have not been granted refuge in recent months.”

Pastors and parishioners arrested. Declines in worship attendance. Sacred spaces violated. Ministries to vulnerable populations ended. Changes in immigration policy and enforcement have altered what Christian ministry looks like in America.

Seeking Justice in the Courts

As churches and Christian ministries seek to minister to and advocate for those being detained and deported, some denominations are also fighting back in the courtroom. Faith groups have filed multiple lawsuits to block immigration raids on church property (which includes not just the sanctuaries and other parts of buildings but also the parking lots). The legal process, however, is moving slowly and inconsistently.

Although the federal government has long had a policy barring immigration raids at “protected” or “sensitive” sites like houses of worship and schools, the Trump administration rescinded that directive early on. Several associations of Quaker congregations quickly filed suit.

“The troubling nature of the policy goes beyond just houses of worship with sanctuary programs — it is that ICE could enter religious and sacred spaces whenever it wants,” argued Skye Perryman, president and CEO of Democracy Forward (the group providing the lawyers for the case).

The Quakers were soon joined in their litigation by the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and a Sikh Temple in California. In February, a federal judge issued a preliminary injunction in that case to bar immigration raids — but only for the plaintiffs, not at all houses of worship. Despite that, immigration officials appeared to conduct a stakeout in March at a CBF church holding English as a Second Language classes.

“Churches are supposed to be safe spaces for us to share God’s word and God’s love. I’m grateful that no one was harmed but I am concerned for the sanctity of this church and others who are involved in serving our state,” Larry Hovis, executive coordinator of CBF North Carolina, said in response to the incident. “I’m also grateful for the court order that protects our churches to minister to their neighbors without the fear of warrantless raids for immigration enforcement.”

After the Friends (as Quakers often call themselves) led the first round of litigation, a group of 27 religious groups filed a similar lawsuit. With the Mennonite Church USA serving as the lead plaintiff, the case can be shorthanded as Mennonite Church USA et al. v. U.S. Department of Homeland Security et al. or just “Mennonites versus Homeland Security.”

Joining the Mennonites in the suit were several other Protestant traditions like the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Church of the Brethren, Episcopal Church, General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), and some regional United Church of Christ and United Methodist Church bodies. Additional plaintiffs include a Hispanic Baptist convention in Texas, multiple Jewish groups, the Unitarian Universalist Association, and the state council of churches for Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin.

“What we are fighting for today is not only for respect or for due process and respect for human rights, but we are fighting for the end of a system that has historically exploited the vulnerable,” Rev. Carlos Malavé of the Latino Christian National Network said during a vigil at National City Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in Washington, D.C., in April to support the litigation. “We will confront the Pharaoh of our time. And we will even confront the detractors in our own Christian family. We will do so with courage and faith, trusting in our God.”

Clergy hold signs at National Christian Church in Washington, D.C., just before the start of a vigil on April 3, 2025, to support a lawsuit seeking to block immigration raids at houses of worship. (Brian Kaylor/Word&Way)

Unlike in the Quaker, Cooperative Baptist, and Sikh case, the judge in the Mennonite et al. suit refused to issue an injunction. The Trump-appointed judge argued the plaintiffs had not experienced significant harm from the policy change. Given the numerous incidents documented since then — especially the incident at Downey Memorial Christian Church, which is part of a plaintiff denomination — we question if the judge’s logic still holds. That could be tested in a new suit filed last week.

Echoing the arguments in the earlier cases, additional groups are seeking to protect their congregational spaces. The new plaintiffs include the American Baptist Churches USA, Alliance of Baptists, Metropolitan Community Churches, five regional synods of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, and three regional Quaker groups (who weren’t part of the earlier suit). The case specifically cites several incidents of immigration arrests on church property this year.

“As people of faith, we cannot abide losing the basic right to provide care and compassion,” said Bishop Brenda Bos of the ELCA’s Southwest California Synod. “Not only are our spaces no longer guaranteed safety, but our worship services, educational events, and social services have all been harmed by the rescission of sensitive space protection. Our call is love our neighbor, and we have been denied the ability to live out that call.”

Considering the significant impact on congregations in the detaining of pastors and other Christians (and Homeland Security’s co-opting of Scripture to justify hunting immigrants), it makes sense that so many denominational bodies are signing onto lawsuits. When the government is arresting Jesus the carpenter and other law-abiding Christians, we shouldn’t be surprised that churches are seeking sanctuary in the courtroom.

As a public witness,

Brian Kaylor & Beau Underwood

A Public Witness is a reader-supported publication of Word&Way. To receive new posts and support our journalism ministry, subscribe today.