The killing of a Ferguson, Mo., teenager and the riots that followed can teach Christ-followers and churches a few lessons, a church planter and a suburban pastor believe.

The shooting death of unarmed African-American Michael Brown on Aug. 9 led to vandalism and looting on Aug. 10 while others were trying to honor Brown with a candlelight vigil. Ferguson suffered rioting for several days.

Leaders in the area have indicated that the reaction was a result of long-standing tension between a predominantly African-American community and its nearly all-white police force.

Owen Taylor, Churchnet (also known as the Baptist General Convention of Missouri) church planting team leader, believes all churches can learn some lessons from Ferguson. He sees the riots as a means for helping congregations and individuals to examine their understanding of racism and their own part in its continuation.

Congregations should examine their understanding of justice, particularly social and economic justice, he said. And churches should be asking themselves how they might help those who feel trapped and with no options.

Scott Stearman, pastor of Kirkwood Baptist Church in Kirkwood, another St. Louis suburb, points to institutional racism. While individuals may nudge closer to overcoming racism, most communities, including congregations, have not, he said.

Realities of racism are rooted in all communities, not just urban settings, Stearman said. “There is still a lot of denial of the fundamental facts” — racial profiling, the income gap, and the search, arrest and incarceration rates of African Americans. “These are facts that we must deal with,” he said.

Addressing long-term systemic injustices is “complicated and hard,” he added, because those injustices cross “from spiritual to moral to political” realms and “it’s hard for congregations to get there,” he said. While Christians may understand justice in a spiritual sense, implementing justice in practical ways in community is difficult, he explained.

“We also have to face the questions dealing with our own prejudices and how they determine whether we are willing to help and get involved with people, issues and politics,” Taylor said.

Both leaders agreed that developing relationships across racial, social and economic lines is the first step in moving toward systemic change.

Taylor pointed out that believers need to be willing to “move out of our comfort zones” and get involved politically. “It will also require us to work together with all the faith groups around us to have a united front in standing up for those who are not receiving justice in our society and under the legal system.”

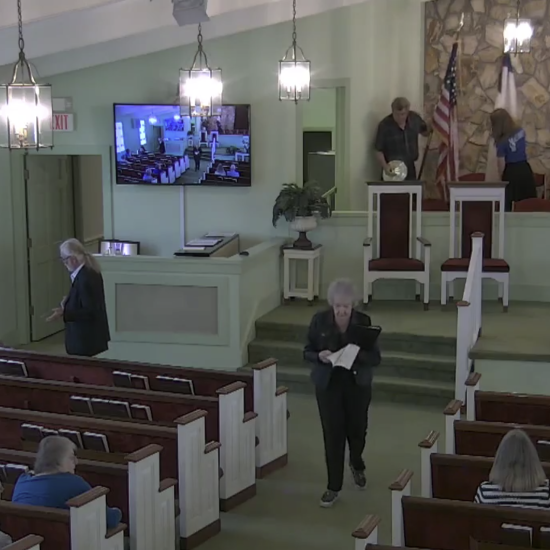

Kirkwood Baptist members began an annual outreach called Hands On Kirkwood in 2006 as a way to reach out to African-American neighborhoods in town. In February 2008, a gunman shot two police officers and three city officials at a Kirkwood City Council meeting. The mayor died seven months later. The incident “spurred” the church to continue to minister, Stearman said.

The Kirkwood church’s involvement in the New Baptist Covenant, a loose alliance of racially and theologically diverse Baptist groups, also has been an impetus to participate in the broader community.

Though Martin Luther King Jr. once called 11 a.m. each Sunday as the “most segregated hour,” Stearman believes that each community needs space in which to worship in its own tradition. The goal of the New Baptist Covenant is “not to worry so much about the 11 o’clock hour but toward working together on projects,” he said. It’s more about “carrying the gospel to society side by side.”

Stearman added that a lot of finger-pointing about the Ferguson shooting and riots has been done on social media. Patience, rather than recrimination, is needed to overcome injustice.

“We…have to work at being patient with each other,” Stearman said. “We need to have patience and love over fundamental social issues.”