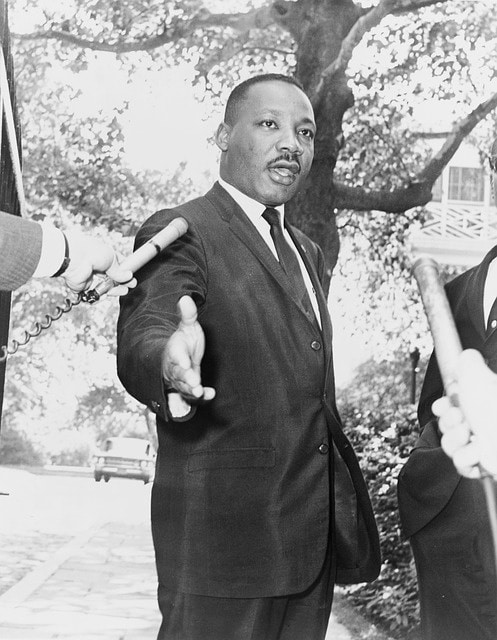

The name of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. — much like the name of German monk Martin Luther — remains quickly recognizable. However, King’s birth name — Michael King — does not bring the same level of familiarity. How did Michael King Jr. become Martin Luther King Jr.? That answer involves a meeting of the Baptist World Alliance just as Adolf Hitler took control of the land of Protestant reformer Martin Luther.

“Little Mike” became Martin Luter King Jr. after his father was moved by attending a 1934 Baptist World Alliance Meeting. (Pixabay)In 1934, the BWA held its fifth Baptist World Congress in Berlin, Germany. Delayed a year due to economic woes, particularly as the Great Depression intensified in the U.S., controversy about the location emerged after the rise of Hitler in 1933. Although some Baptists wanted to move the venue due to the already-evident anti-Jewish agenda of Hitler, the BWA leadership decided holding a meeting in Berlin could provide an opportunity to showcase Baptist unity with German Baptists and offer a strong message about Baptist convictions.

“Little Mike” became Martin Luter King Jr. after his father was moved by attending a 1934 Baptist World Alliance Meeting. (Pixabay)In 1934, the BWA held its fifth Baptist World Congress in Berlin, Germany. Delayed a year due to economic woes, particularly as the Great Depression intensified in the U.S., controversy about the location emerged after the rise of Hitler in 1933. Although some Baptists wanted to move the venue due to the already-evident anti-Jewish agenda of Hitler, the BWA leadership decided holding a meeting in Berlin could provide an opportunity to showcase Baptist unity with German Baptists and offer a strong message about Baptist convictions.

On the latter account, the BWA did offer a prophetic message condemning the very racism motivating Hitler’s regime. The BWA’s resolution on “Racialism,” noted that “this Congress deplores and condemns as a violation of the law of God the Heavenly Father, all racial animosity and every form of oppression or unfair discrimination toward the Jews, toward coloured people or toward subject races in any part of the world.” The resolution called for “respect for human personality regardless of race” and quoted Galatians 3:8 about there being “neither Greek nor Jew.”

In his new book on “Baptists, Jews and the Holocaust,” American Baptist Churches USA General Secretary Lee Spitzer argues the 1934 resolution “deserves a place alongside the universally acknowledged Barmen Declaration.” While the BWA resolution offered a “forthright defense of the general Jewish population and their civil rights,” Spitzer noted, the Barmen “ignored the issue” to instead focus “on the right of the German church to choose its leaders without interference from the state.”

“Karl Barth’s ‘nein’ might be legendary and famous,” Spitzer added, “but the Baptist ‘no’ to anti-Semitism, declared in the German capital with the Nazi government watching, was more comprehensive.”

Also watching as Baptists issued that reputation of anti-Semitism espoused by Hitler was an African-American pastor named Michael King Sr. Then pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Ga., he traveled to the Congress after visiting other places in Europe and the Middle East. He was so impressed by what he learned about the German reformer during the trip that after returning to the U.S., he changed both his name and the name of his five-year-old son. He became Martin Luther King Sr. and “Little Mike” became Martin Luther King Jr. In a sense, a trip to a BWA meeting led to the “birth” of Martin Luther King Sr. and Martin Luther King Jr.

Five years later, “Daddy King” — as the elder MLK became known decades later after his son’s prominence — chaired the local arrangements committee for the next Baptist World Congress, which was held in Atlanta in 1939. That meeting, which was held in the Jim Crow South was perhaps the first fully-integrated meeting in the racially-segregated city.

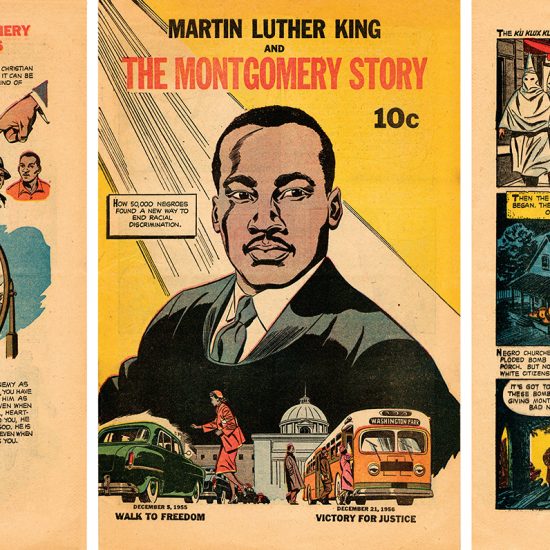

A few decades later, Martin Luther King Jr. personified the vision of the Berlin and Atlanta BWA gatherings as he marched arm-in-arm with white pastors and Jewish rabbis to advocate for racial quality and civil rights. As he did so, he once again associated the name “Martin Luther” with reformation, bringing religious and political changes.